Source: Waging Nonviolence

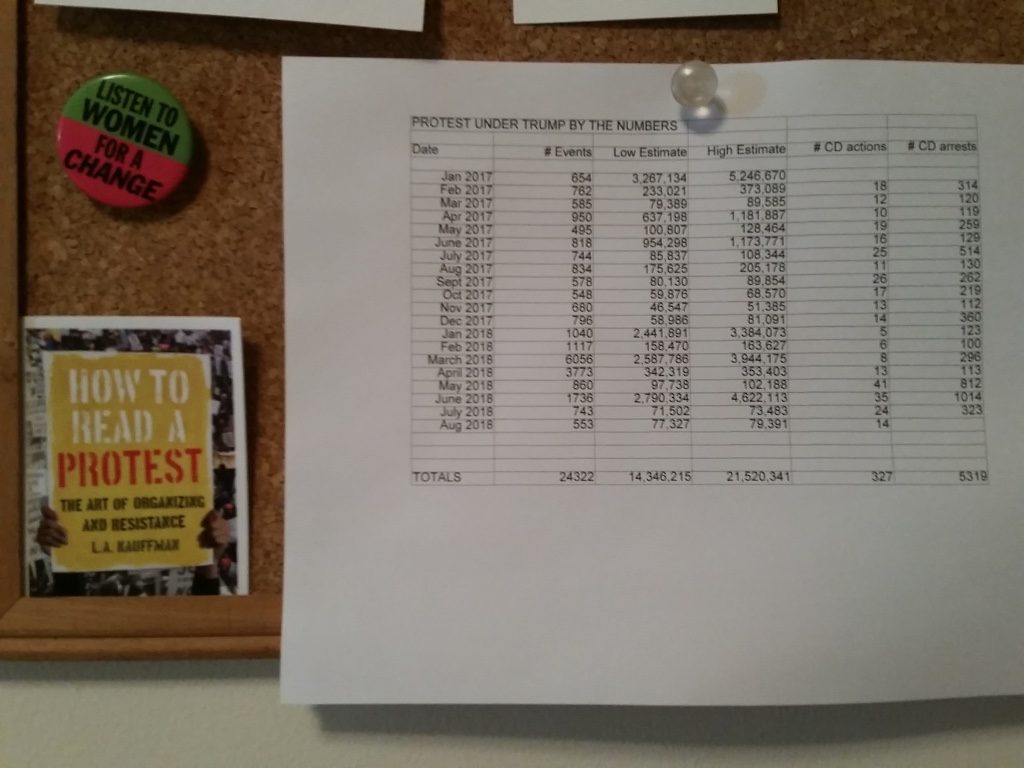

Where do you look for hope in dark times? Longtime organizer and author L.A. Kauffman looks to a chart she keeps on her wall that tracks how many people have participated in protests since January 2017. Right now that number is upwards of 21.5 million.

“It’s part of my organizing geekdom,” she says. But it’s also the best visual reminder of a fact that’s easily overlooked: We are living in a time of unprecedented protest.

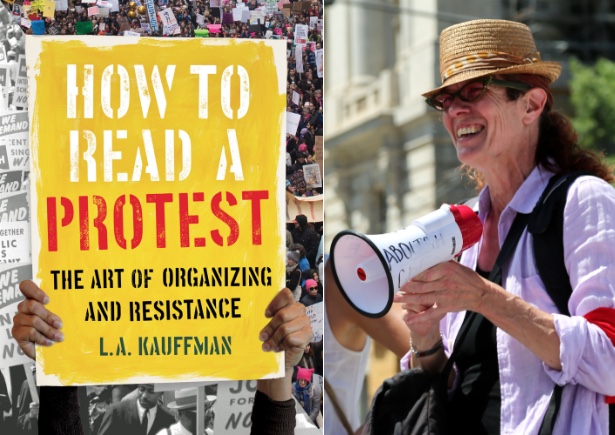

To help people better understand and harness the potential of this wave of action, Kauffman has written a new book called “How to Read a Protest: The Art of Organizing and Resistance.” Its focus is a comparative study of two mass protests — the 1963 March on Washington and the 2017 Women’s March — showing the ways in which protest and organizing have changed over the last 50 years.

In one clear example, Kauffman contrasts the signs people carried at the two protests. While the Women’s March gained attention for its idiosyncratic and irreverent messaging, the signs at the 1963 march were all fairly uniform. Through research, Kauffman discovered the reason for this: An outright ban on homemade signs by the 1963 march’s leadership — something that seems unfathomable, if not impossible, to control today.

Kauffman is no stranger to mass protests. She served as the mobilization coordinator for mass demonstrations against the Iraq War and the 2004 march outside the Republican National Convention, experiences that have helped her appreciate the standard-setting role of the 1963 march. But her research on the homemade sign ban, along with other myth-busting insights, led her to view it — and the mass marches it influenced — in a new light.

Ultimately, for Kauffman, the Women’s March represents something new in the history of mass protest. I spoke to her about her findings, how they explain the current state of resistance and the hope that represents.

Tell us about your experience at the Women’s March in Washington, D.C.

I have been to a lot of big protest marches, and — frankly — they have sometimes come to seem kind of dreary and boring to me. I’ve even found some of the ones I helped organize kind of uninspiring. So I went to the Women’s March in 2017 not really having that high of expectations for what the experience was going to be like, and I was absolutely blown away by the sea of women, the way that it was so fluid, so dynamic, so organic, so different, so much more a feeling of an uprising than of a traditional mobilization. It didn’t feel like it had been engineered from above, like we were all following a single plan. It felt like we were all converging in a bottom-up way that was extraordinary. And I was immediately struck by the signs, by what a high percentage of them were handmade and how different that felt. There was something in the signage that told me a different story than I had ever seen at one of these mass mobilizations.

What was it that made the Women’s March signs stand out so much? They received a lot of media attention and are one of the things people remember most from that day.

Well, the question is more: Why was everyone so moved to make them? What was the magic signal that went through the ether that told everyone “Hey, make your own sign for this one. You don’t show up and get the one that’s pre-printed and handed out.” I feel like it was a collective reclaiming of voice by women and allies of other genders, but primarily by women. The historic silencing of women and women’s attempts to break through that are the central theme of feminism. After the horrible loss of the election and the way so many people felt so gutted and devastated, it was like a kind of collective magic at work. All of these women and girls were finding their voice by making signs and coming together to literally enact community in the streets.

What led you to study the 1963 March on Washington?

I had been living with questions about mass marches and what they do and don’t do for a long time. And I just decided at some point to pick up some of the existing published accounts of the 1963 March on Washington. I realized I had never really read in great detail how it came together.

When I discovered the fact that all of the signs there were controlled by the leadership, I was completely blown away. That simply isn’t how it’s been done since. And it’s not that it just hasn’t been done, if you’ve been in the position of mobilizing one of these mass protests, it’s hard to even imagine how you could do it. Big crowds are not so easily controlled, right? So, it was this mystery to me from an organizer’s point of view: How the hell did they do that? And why did they want to?

And so I lucked out in that there’s really wonderful archival material about the 1963 March on Washington at the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture. They have this remarkable trove of interviews with the staff organizers, which includes people who are well known — like A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin — but also people who are not well known and who did things like coordinate the bus operation.

So I went deep into organizing geekdom with this. Something like a large-scale bus operation is a specific geeky organizing undertaking, but it has a lot of significance because it’s typically how you get huge numbers of people to a protest, and how it’s done tells you a lot about things like the health and mobilizing capacity of the groups involved. So I dug through the archives, and I discovered all these fascinating things about how the 1963 march was run and how tightly controlled every aspect of it was — the signs just being one example.

What were some other take-aways from your research?

I had not previously appreciated the fact that the 1963 March on Washington really was the first mass march in American history. Even though I knew American history reasonably well, I somehow had some vision of 1930s mass marches, for labor or something. But it didn’t happen. There was never really a mass march until 1963 in America. And it was partly because of the novelty of doing it, and the fears surrounding it, that they controlled it so tightly.

But it was also a different kind of leadership and a different kind of organizational culture. It was a very male culture. It was mostly black male culture, but it was very gendered, and women were really sidelined from the organizing process in all kinds of very sharp ways. And it was partly coming out of an old left tradition of greater conformity, more hierarchical structures of decision making and mobilizing — a whole series of characteristics that are no longer central to the organizing culture of the left.

So it was fascinating in itself, but it helped throw into relief the ways in which the women’s marches were so different and the way they came together. It was such a departure from the tradition that was started with the 1963 March on Washington and then carried forward in all these other mobilizations, including the ones that I worked on from the inside.

What kind of lessons can we draw from this in terms of effectiveness?

We have a sort of vague idea of the 1963 march as this turning point in American history. I think that we assume it strengthened the organizations that were behind it, but there’s very little evidence it did. If anything, it weakened them. I went back and looked to see what happened in terms of organizational membership and fundraising after the march, and rather than successfully pull those folks into civil rights organizing, the march itself marked the high point for a lot of the organizations. Their memberships declined afterwards. They were too depleted to do anything with [all the new contact information they had gathered].

Whether or not a more bottom-up organizing structure would have facilitated that kind of absorption, we can’t know. But certainly the way it played out — with the shots being called by the leaders at the top and implemented by a variety of supportive administrative folks — it just didn’t happen.

By contrast, the Women’s March itself, as an organization, did continue forward and form chapters, and they just played an extremely important role in the Brett Kavanaugh fight. People also formed their own groups in the wake of the marches — some 5,000-6,000 of them, most of which are affiliated with the Indivisible network now. So there was this enormous surge of organizational growth after the women’s marches, but it was independent, grassroots bottom-up.

With that in mind, could you talk more about where things are at since you finished the book? Where has this movement gone in the past almost two years?

That’s a big question. The history is unfolding so much before us that I’m reluctant to make a lot of grand proclamations about what we’re seeing politically because it’s all very fluid and very unsure. It’s very unclear where the country is heading and whether the rising tide of authoritarianism can be stopped, whether those who are committed to brutal minority rule can be stopped.

What is clear is that more people have taken part in protests over the last two years, by far, than any point in American history. I don’t think people live with this realization in their bones. I don’t think people walk around realizing that this is the greatest flowering of protest activity ever in American history. There are many more people taking part in marches and rallies and other kinds of protests than during the height of the Vietnam War or the 1930s. It’s just extraordinary. And so we have very high levels of mobilization, very high levels of organizing.

The number of groups connected with the Indivisible network has contracted slightly since the initial 6,000. It’s down to about 5,000. But that’s pretty modest consolidation for two years, in my opinion. And the most generous estimates of how many Tea Party groups there were [put the number at] 800-1,000. So the scale of what has been happening — in terms of these little resistance groups — is much larger, and it’s much more geographically dispersed. There aren’t just more people protesting, there are people protesting in more places. There aren’t just more groups organizing, there are more groups organizing in more congressional districts, in more parts of the country.

Again, that may or may not be adequate to turn the tide. It’s not clear to me. The forces that are suppressing votes, disenfranchising people, gerrymandering, and pouring dark money into campaigns — all of these profoundly undemocratic means that are designed to undermine democracy further and ensure continued rule by an extremist minority — have been very powerful and effective. We can have our women-led decentralized leaderful groups going out to register voters, and then — in one fell swoop — they can wipe 70,000 of them off a server, and all of that progress is erased. So, while I am not at all clear we have it within our means to win in any meaningful sense right now, I do think the fact that people are in motion, converging and mobilizing at this scale is grounds for hope. It’s our best grounds for hope.

There have been a number of women-led nonviolent direct actions in recent months. Is that a sign that this wave of protest is escalating?

Absolutely. Just numerically, direct action has been on the rise since the spring. I keep a chart on my wall — as part of my organizing geekdom — that tracks the number of people who have participated in protest since January 2017, and I look at it all the time. Direct action and civil disobedience were really quite rare in the first year after Trump took office. There were actions and they were worthy actions, but they tended to be like 20 people risking arrest, and they were in many cases continuations of fights that had happened before, as opposed to direct actions specifically organized in response to the ascendancy of Trump.

It was really the family separation policy that changed that. In June of 2018, for the first time since Trump took office, there were more than a thousand people arrested in civil disobedience actions around the country over the course of the month. The previous months’ tallies had varied. There were some moments around the health care and tax fights that were higher, but most months before then were like 120 arrests over the course of a whole month. And then you see the jump in June. Although I have not yet confirmed these numbers with the Capitol Police, one of the lead organizers of the Kavanaugh protests told me there were more than 1,200 arrests within the span of those two-plus weeks.

So the numbers are going up, and I’m certainly hearing from a number of key organizers that there’s an interest in continued work on that front. I think there are plans in the works for larger direct action trainings and direct actions in the coming months. But we still have not seen anything on the scale of say the actions we had during the peak period of the global justice movement at the turn of the millennium, with 10,000-20,000 people taking part in direct action. And I don’t know whether we will see that. But there’s no question that people are beginning to use of some of the stronger tools in the toolbox of nonviolent action.

Has losing the Kavanaugh fight hurt momentum in any way?

It was a devastating loss. There’s no question. But the Democrats were ready to concede the loss back in the summer. It only became a real fight because of the grassroots resistance. One hopes that some of the centrist Democrats will take a lesson from that. It was really because of the hundreds of women who disrupted the first round of hearings with Kavanaugh that political space opened up for Sens. Booker and Hirono to release documents that were supposed to be kept confidential, showing Kavanaugh had lied. I believe that resistance may have also been what made Dr. Blasey Ford feel able to come forward with her testimony. We should remember, it wasn’t until the very last minute that Mitch McConnell was confident that he had the votes.

That isn’t the kind of win we wanted, but that is a win compared to just rolling over the way that the Democrats were ready to do. I hope that the lesson people take away from that is: Fight as hard as you can with every single battle. It’s what I think people are doing with their electoral work. People are fighting in districts that the Democratic National Committee had written off as unwinnable, and they’re making big inroads. Learning not to accept this sense of inevitability and that vigorous work from the grassroots — not orchestrated by the Democratic Party — is key to fighting on every front.

Bryan Farrell is a Waging Nonviolence co-founder and editor. He also hosts and produces WNV’s podcast, We Are Many. His work has appeared in The Guardian, The Nation, Mother Jones, Slate, Grist and Earth Island Journal. Follow him on Twitter @bryanwith2eyes.