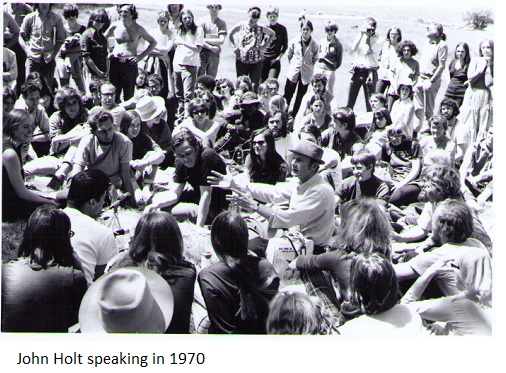

“As for the future, most of those who talk and write about it do so as if it already existed and as if we were being inexorably carried toward it, like passengers on a train moving toward a place they had not seen and could only wonder about. This is of course not true. The future does not exist. It has not been made. It is made only as we make it. The question we should be asking ourselves is what sort of future do we want?” ~ John Holt (April 14, 1923 – September 14, 1985)

The stereotype of homeschooling as the haven for conservative, religious ideologues overshadows the movement’s radically progressive roots. One of the movement’s foremost pioneers, John Holt, was an egalitarian atheist who explicitly opposed patriarchy, corresponded with progressive thinkers including Paul Goodman and Noam Chomsky, and helped initiate the still emerging children’s rights movement.

High profile homeschoolers like Republican E. Ray Moore help maintain the entrenched stereotype that homeschooling families are necessarily conservative Christians. In April 2014, Moore, then a South Carolina candidate for lieutenant governor, stated that Christians are facing a cultural war facilitated by an impious, “socialistic” public school system. “We cannot win this war we’re in as long as we keep handing our children over to the enemy to educate,” said Moore, who homeschooled his son.[1] Given such prominent representations of homeschoolers many may be surprised that the man significantly, though not singularly, responsible for initiating the homeschool movement, John Holt, was a radical progressive.

John Holt, who died September 14, 1985, was a social critic and organizer who made almost everyone uncomfortable, but probably none more than “family value” religious conservatives. Holt’s stated aim in promoting homeschooling was to liberate children from what he saw as among the most authoritarian, humanity-depriving institutions of all human creations: compulsory education. An institution, he believed, that violated children’s basic right to control their “minds and thoughts.” In Instead of Education: Ways to Help People Do Things Better (1976) Holt wrote:

“That means, the right to decide for ourselves how we will explore the world around us, think about our own and other persons’ experiences, and find and make the meaning of our own lives. Whoever takes that right away from us…attacks the very center of our being and does us a most profound and lasting injury.”[2]

Radically, Holt lays claim to children’s right to that most cherished of enlightenment ideals, freedom of thought. Nearly 300 years earlier, in 1670, the philosophical pioneer of European free thought, Spinoza, wrote “a government that attempts to control men’s minds is regarded as tyrannical, and a sovereign is thought to wrong his subjects and infringe their right when he seeks to prescribe for every man what he should accept as true and reject as false.”[3]

Inspired by his empathetic experience teaching fifth grade students, Holt authored How Children Fail (1964), in which he argues, as Patrick Farenga explains it, that forced learning centered on pleasing educational authority figures and pursuing institutional benchmarks and rewards makes children “unnaturally self-conscious about learning and stifles children’s initiative and creativity….”[4] His work earned him significant societal acknowledgement in school reform circles. He also received opportunities to appear on mainstream media programs and to be a visiting lecturer at both Harvard and Berkeley.

Compulsory Schooling: An Education in Authoritarianism

Holt was disillusioned with efforts to reform schools, however, and was inspired by Austrianphilosopher Ivan Illich’s work. Illich founded the Intercultural Documentation Center in Cuernavaca, Mexico, criticized Western cultural imperialism, and authored a groundbreaking critique of institutionalization, Deschooling Society (1970). Farenga writes that Holt was particularly influenced by Illich’s contention, in Deschooling Society, that

“school serves a deep social function by firmly maintaining the status quo of social class for the majority of students. Further, schools view education as a commodity they sell, rather than as a life-long process they can aid, and this, according to Illich, creates a substance that is not equally distributed, is used to judge people unfairly, and — based on their lack of school credentials — prevents people from assuming roles they are otherwise qualified for.”[5]

Holt would go on to distinguish between two visions for education. In an August 1, 1970 letter to the editor to Commentary magazine, he wrote: “Most people define education as sculpture, making children what we want them to be. I and others in this movement define it as gardening, helping children to grow and to find what they want to be.”

Though initially supportive of “traditional education” Holt wrote that he came to view the very design of the institution of school as inherently at odds with idealist objectives including critical thinking and moral equality. Holt argued it was absurd to think that a place “where we coerce, bribe, wheedle, motivate, grade, rank, and label [children]” can be the same place they learn to “resist advertising men and behavior modifiers.” [6] Forsaking the institutional credibility he had been given as an advocate for reform, Holt made himself a principled outsider in denouncing the dominant education institution.

Holt wrote decades before progressive, democratic educators such as Henry Giroux, bell hooks, and Bill Ayers assailed the way in which the dominant system of education promoted obedience and conformity. He also wrote more forcefully in condemning this system then they do today:

“Education, with its supporting system of compulsory and competitive schooling, all its carrots and sticks, its grades, diplomas, and credentials, now seems to me perhaps the most authoritarian and dangerous of all the social inventions of mankind. It is the deepest foundation of the modern and worldwide slave state, in which most people feel themselves to be nothing but producers, consumers, spectators, and ‘fans,’ driven more and more, in all parts of their lives, by greed, envy, and fear. My concern is not to improve ‘education’ but to do away with it, to end the ugly and antihuman business of people-shaping and let people shape themselves” [7]

Such criticism did not occur in a vacuum, however, but was in part inspired by public intellectual, Paul Goodman’s classic leftist work, Growing Up Absurd (1960). As Holt’s 1964 work called for educational reform, Goodman’s work of the same year, Compulsory Mis-education and The Community of Scholars, set a tone Holt would later take-up. Goodman, who was a pacifist and among the first openly bisexual public figures, wrote: “it is simply a superstition, an official superstition and a mass superstition, that the way to educate the majority of the young is to pen them up in schools during their adolescence and early adulthood.” [8]

Alternatives to Compulsory Education

If not traditional schools then what? In Instead of Education Holt promoted and discussed alternative means of exchanging ideas and cultivating learning in a humane manner: “non-compulsory schools, learning centers, and informal learning arrangements in action.”[9] Holt suggested the public library as a “very good model” for those seeking an authentic, organic learning experience. The virtues of the library, he argued, include: its open availability without stipulations for attendance; that it had no testing component, no grade ranking, and no dictation of what must be learned. [10]

Holt also proposed a radical abandonment of the institution he believed was responsible for generating human oppression. As a start he suggested the creation of a “Children’s Underground Railroad” purposed “to help children escape from S-chools.”

“Some may say that such a railroad would be unfair, since only a few children could get on it. But most slaves could not escape from slavery, either, yet no one suggested or would suggest that because all the slaves could not be freed, none should be” [11]

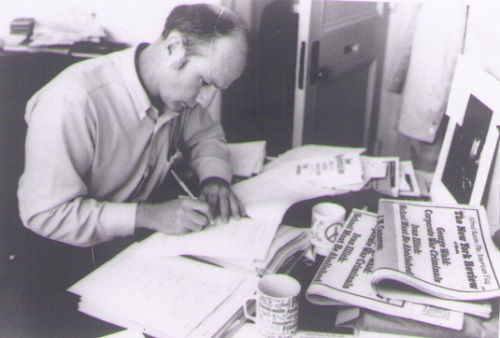

Inspired by correspondence with parents Holt began what might have been the nation’s first homeschooling newsletter, Growing Without Schooling (GWS) in August 1977. Today homeschooling is practiced by people of varied political, philosophical, and religious backgrounds. Some progressives embrace homeschool as a means to organically nourishing critical consciousness.

These striking critiques of dominant education had more to do with an intellectual affinity with the enlightenment, then the desire of those such as E. Ray Moore to escape the “evils” of secularism. “John (Holt) was an atheist,” explained prominent homeschooling advocate and former Holt associate, Patrick Farenga, in an August 2014 email interview. Farenga took over as publisher of Growing Without Schooling after Holt’s death, and has probably done the most to preserve and help understand his legacy. In a June 12, 1972 letter, Holt wrote that he shared his friend A.S. Neil’s “view that in a personal sense death is simply the end of life.” [12]

What’s more, Holt’s most radical work advocating a number of still controversial children’s rights, Escape from Childhood: The Needs and Rights of Children (1974), “made many conservative Christians uncomfortable with his views and therefore suspicious of identifying with his ideas about homeschooling,” said Farenga. Indeed the work features a number of controversial theories that would likely not sit well with many progressives either. Embracing the critical disposition to question everything, the work scrutinizes conventional thinking, and forces readers to identify solid ground for their assumedly right and fitting beliefs and practices concerning children.

Escape from Childhood is a testament to Holt’s progressive, secular and, in some important ways, feminist philosophy. Crediting feminist author, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectics of Sex as an influence, Holt assailed the patriarchal family for making not only adult women but also male and female children objects of ownership and control. [13] He wrote that most apologists for the “traditional” family did so in order to preserve what amounted to “a miniature dictatorship…in which the child learns to live under and submit to absolute and unquestionable power. It is training for slavery.” [14] Holt also suggested the need to “re-create the extended family,” in which relationships could develop organically, rather than according to bloodlines. [15]

Rights for Children

Not only did he help pioneer the homeschool movement, Holt also helped launch the children’s rights movement. Above all Escape from Childhood is a radical critique of youthism, the unjustified discrimination and oppression of the young. The work explains how the young, not unlike women, the LGBTQ community, and people of color, have been categorized as not only “other” but also as “inferior” by those in power: in this case, adults. Holt helps us become conscious of the way in which “child” is a category of identity historically determined by those in power, and used to assert and justify power’s sense of importance and superiority at the expense of the “other.” Adults have objectified children, basing their value on a limited scope of adult-pleasing behaviors and interests.

Holt’s general critique raises profound questions for those of us with the humility to question deeply lodged assumptions about ourselves and others. The work proposes to make a number of rights “available” to young people who want them. Among them are the right to be treated “no worse than an adult would be” by the law, the rights to vote, work, travel, privacy, financial transactions, and the rights to determine one’s education, familial group and place of residency.[16]

To understand Holt’s argument it is worth considering his contention that children should have the right to drive, with no bearing on their age. Holt believes the right to drive should be based solely on the capability to drive safely. He even mentions he thinks the laws should be stricter and that tests should be given more frequently to reduce unfit drivers. His main point is that it is not reasonable to exclude members of society from having the opportunity to prove their driving competency on the arbitrary basis of age. [17] Such age-based laws discriminate against those who do not fit stereotypes and, Holt believes, without good reason: “it is grossly unjust to discriminate in law against anyone merely because he is a member of a statistical group. Statistics do not prove, and could never prove, that just because a person is under twenty-five he is a bad driver, or worse than older drivers.” [18]

Feminist works like Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born (1976) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) showed that dominant definitions of femininity and motherhood were social constructions that alienated women from themselves and facilitated sexist oppression. Holt’s Escape from Childhood does something very similar for our understanding of the institution of “childhood” and the oppression it generates.

Holt explained that most view childhood as “a kind of walled garden in which children, being small and weak, are protected from the harshness of the world outside until they become strong and clever enough to cope with it.” [19] Yet most children, he contends, experience “childhood not as a garden but as a prison.” [20] Holt argues that childhood is an oppressive institution, comprised of “attitudes, customs, and laws,” [21] that leads to the marginalization, exploitation, and varied abuses for many children. In ordinary life children “may be in many ways exploited, bullied, humiliated, and mistreated by their families.” [22]

In its March 1974 special issue, “For Free Children,” Ms. Magazine published an excerpt of Escape from Childhood. The piece examined and criticized the way in which most adults, intentionally or not, use children as “love objects, slaves, property.” [23] Holt had in mind behaviors that are today commonplace. Consider for example how adults feel entitled to touch, hug, and kiss children, without being invited by the child or asking or considering the child’s wishes. “Oh, get over here you, I’m your grandpa!” As a parent of four children I have often had to ask family members, friends, and often strangers to give my children, be they 1-year-old or 6-years-old, space, and to respect their bodies and wishes. On other occasions strangers have approached one of my young children in a grocery store to admire their “cuteness,” and, despite their obvious discomfort, the stranger will touch, grab, pinch and/or invade the personal space of the child. When a child recoils in fear, shyness, or a mix of both, the adult reaction is usually to laugh, complain about, or mock the child’s reticence, rather than to consider that perhaps their behavior was inappropriate. From a distinctly adultcentric worldview, such an insight is unthinkable.

Much of this objectification, Holt contends, is likely due to the way “many of us are starved for human contact and affection that may openly be expressed with words of endearment or physical contact.” [24] Interestingly, Holt targets the interrelational impoverishment of dominant masculinity’s ideal of stoic detachment as a potential source for this problem: “Men are really only supposed to touch the women to whom they are closely related, and they are not supposed to touch other men in any affectionate way at all.” [25] Affectionate behavior is perhaps more acceptable for women, he hypothesizes, because they are identified as an “inferior class.”

Nevertheless, this “masculine” behavioral ideal of human selfhood is enacted as the ideal for adult behavior. “…we teach the children this lesson: only ‘little kids’ go around all the time looking enthusiastic and asking silly questions; to be grown-up is to be cool, impassive, untouched, invulnerable.” [26] The bottom line, as he sees it, is that the general adult population dismisses children’s feelings, sensitivities, and experiences in a way that “grown-ups” would never tolerate. [27]

Feminist Sexual Politics

One month after the publication of the first issue of Ms. Magazine, John Holt wrote to Gloria Steinem to say he “enjoyed the first issue” and was looking “forward to further issues.” He also expressed his support for the “Women’s Liberation Movement” [28] In Escape Holt would later make his support for feminist positions, including reproductive rights, explicit.

Writing around the time of the Roe V. Wade decision, Holt criticizes dominant culture for failing to allow “women to decide whether they will have children or not, or how many, but instead treats them in this respect as baby-producing machines controlled by men and the state.” [29] The result of such policies is that women, and the children they are forced to bare, experience “many serious social and emotional problems, from which any humane person would want to spare them.” [30] The clear implication of these statements is that Holt was pro-choice.

These ideas are elaborated on in what may be Holt’s most provocative and challenging chapters, “The Law, The Young, and Sex,” in which he calls for sexual freedom for children. Holt discusses a number of difficulties and uncertainties surrounding this controversial subject, including his own sense that only those who are responsible citizens are entitled to sexual freedom. [31] Holt contends that the “protection” of girls is used to subdue female sexual expression, including that of female adolescents. In order to remove the “dangers’ of sex Holt proposes that society provide ample sex education, birth control information and advice, and male contraceptives. Writing at a time when researchers were conducting experimental testing of precursors to emergency contraceptives, Holt even called for the development of “a safer and easily available retroactive or after-the-event birth control pill.”

Progressive Politics and Fears of Fascism

Throughout his life Holt defended a radical vision of individual freedom coupled with societal responsibility to ensure a good life for the least powerful. On April 4, 1972, Holt wrote Noam Chomsky to share thoughts on the future of his work, namely his interest in spending more time addressing politics. He also discusses political strategy, including how best to improve the likelihood that radical left-wing political ideas are heard in place of right wing views.[32]

Chief among Holt’s identified fears was what he described as spirit of fascism in American society. In a 1970 letter to Paul Goodman, he wrote

“I keep looking for and hoping to find evidence that they are not as callous and greedy and cruel and envious as I fear they are, and I keep getting disappointed. We still are, in fact, at least compared to a great many other places, a relatively free country, but what scares me is the amount of Fascism in people’s spirit. It is the government that so many of our fellow citizens would get if they could that scares me—and I fear we are moving in that direction.” [33]

Today Holt’s supporters know him best for deconstructing institutionalized education and criticizing its implementation to limit human thought and freedom. Less realized is that Holt did not view the education system as a sole actor in fostering such oppression. Signaling awareness of the broader cultural sources of oppression, Holt wrote: “I’m terribly afraid of fascism for my country and it seems to me that there are certain places, much more than others, where fascism is learned—in school, in front of the television set, and almost above all at the wheel of a car.” [34]

And while he considered himself an “evolutionary rather than a revolutionary,” Holt told Paul Goodman that he did not share his certainty that the kind of revolutionary change that many radical young people had in mind was irrational and unnecessary. “I think it is altogether possible that the professions are so corrupt that they will throw off, like a living body rejecting foreign tissue, any group of people who try to reform them. At any rate, it is an arguable point, and I don’t think we can dismiss as simply foolish or misguided people who take that position.”[35]

Ecological disaster was among the issues Holt believed required serious and immediate attention. Holt wrote that Goodman was mistaken to exalt Western culture, as he had in an earlier in-person conversation, since it had brought humankind

“to the edge of a cliff. An observer living among us, reporting back home to his distant star, would have to say that the prospects for humanity are not very good, that there is every reason to believe that either through war or through our systematic destruction of our environment we may very soon make the world uninhabitable for us and indeed for all living creatures.” [36]

For many of the time these words were alarmist or hyperbolic. Today they ring prophetically accurate as an August 2014 draft report by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned of the catastrophic trajectory of human-driven climate change. As Bloomberg reported, the report draws on hundreds of scholarly studies and warns that the present course of climate change threatens the globe with “severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts for people and ecosystems,” including a rate of warming change greater than that which brought the end of the Ice Age and increase in sea-levels by as much as 23 feet.

Plight of the Poor: Pursuing a Progressive Social Vision

In addition to his critique of the violation of the freedom from physical and intellectual coercion, [37] Holt believed society had a moral obligation to come to the aid of the most marginalized of its population. In Escape from Childhood Holt makes a direct, plainspoken case for “the right to a guaranteed income.” Being truly free requires economic self-sufficiency, he argued, but many marginalized people lack these means for such economic independence. Those who are marginalized, particularly women and children, are generally reliant on jobholders or breadwinners. Such a state of dependency, contends Holt, robs them of authentic and meaningful human liberty. “The real test of the quality of life in a nation, as in a community, is how well the poorest people in it live.”[38]

Acutely aware of the role class played in movements of his time, Holt wrote that when most speak of rights for women and children they are generally “talking mostly of the upper-middle and wealthy classes, where women and even the young are more likely to have some money of their own or where it will be easier for them to get some of whatever jobs there are or where they can more easily get help from other people who do have money.” [39] This leaves out the “lower-middle-class and poor women and children” who need more than to merely have barriers removed from their progress but also assistance to ameliorate their structural and more complex disadvantages. “For this reason the right of everyone to choose to be independent can hardly be fully meaningful except in a society that gives everyone some guaranteed minimum income.”[40] Thus Holt also shows himself to be a surprisingly intersectional social critic, recognizing the ways in which various social positions and classifications intersect to foster a more complicated experience of oppression.

For Holt it is a given that women as well as men, regardless of marital status, or age deserve such assistance. His aim is to convince the reader that children, too, deserve such guaranteed income. Why does Holt want such a right for children? Financial independence would enable children to enjoy the rights to “leave home, to travel, to seek other guardians, to live where they choose.”[41]

Conclusion

Today progressive politics is almost unthinkingly linked with support for the institutionalized K-12 education system. For example, a cornerstone of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s progressive agenda is a full-day universal pre-k program. Meanwhile homeschooling is presumed to be inherently conservative, fundamentalist, and regressive. In addition to being overly simplistic such associations fail to acknowledge the anti-authoritarian, democratic, progressives thinkers such as Ivan Illich, Paul Goodman, and John Holt who feared the schooling system was a corrosive tool of power. Such associations also fail to acknowledge the progressive lineage of the homeschool movement.

The pioneer of the homeschool movement, John Holt, was an atheist who was inspired by and shared an affinity with progressive intellectuals including Paul Goodman, Noam Chomsky, and Gloria Steinem. He favored reproductive rights for women, a guaranteed minimum income for the poor, and sought to foster a movement to alleviate one of the most vulnerable and underserved groups in society of their oppression: children. More than this Holt viewed his efforts to dismantle the dominant education system as a cornerstone in his progressive politics. As he wrote in Instead of Education:

“To those who think of themselves as Radicals, and who detest, as I do, the idea of a society of winners and losers, I say, change it if you can. But don’t imagine that you’re changing it by talking against it in S-chool, or even by trying to make all your students into winners. A winner-loser society is not going to be changed by its winners; a society run by a few people at the top is not going to be changed by putting some other people up there.” [42]

Whatever one may think of homeschooling, let us at least recognize the radically progressive moral and political motivations of one of the movement’s principle founders, John Holt. Failing to do so, we may overlook an important, if not fundamental, avenue for significant social change, as well as dishonor the life of someone who spent much of his adulthood laboring for a better world.

***

Jeffrey Nall holds a master’s of liberal studies from Rollins College and a Ph.D. from Florida Atlantic University. He is an adjunct professor at two colleges where he teaches philosophy, critical thinking, and gender studies. Nall is the author of Feminism and the Mastery of Women and Childbirth: an Ecofeminist Examination of the Cultural Maiming and Reclaiming of Maternal Agency During Childbirth (Academica Press, 2014). He can be reached at http://www.jeffreynall.com/

Footnotes:

[1] Rebecca Klein, “GOP Candidate Says Christians Must Pull Their Kids Out of ‘Godless’ Public Schools,” Huffington Post, April 22, 2014 http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/22/ray-moore-public-schools_n_5192458.html

[2] John Holt, Instead of Education: Ways to Help People Do Things Better (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1976), 4.

[3] Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus/ Theological-Political Treatise, (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2001), 222.

[4] Patrick Farenga, “John Holt and the Origins of Contemporary Homeschooling,” Paths of Learning, 1999 http://mhla.org/information/resourcesarticles/holtorigins.htm

[5] Farenga, “John Holt and the Origins of Contemporary Homeschooling,” http://mhla.org/information/resourcesarticles/holtorigins.htm

[6] Holt, Instead of Education, 204.

[7] Holt, Instead of Education, 4. Holt thus argued that those who called themselves “radical teachers” were engaging in self-deception. To illustrate his point Holt compared the so-called “radical teacher” resisting the emphasis on obedience and conformity from within the system to the “pacifist soldier” who rails against war but continues to fire bullets.

“What does the Army care what he shouts—as long as he continues to shoot. Let any who want to join the Army, join it. One can be an honest soldier… But let’s not tell ourselves that the Army is the Peace Corps and that by joining it we are working for human brotherhood. The same goes for S-chools—the Army for kids. To those who think of themselves as Radicals, and who detest, as I do, the idea of a society of winners and losers, I say, change it if you can. But don’t imagine that you’re changing it by talking against it in S-chool, or even by trying to make all your students into winners. A winner-loser society is not going to be changed by its winners; a society run by a few people at the top is not going to be changed by putting some other people up there.” (206-207).

[8] Paul Goodman, Compulsory Mis-education and The Community of Scholars (New York: Vintage Books, 1964), 140.

[9] Patrick Farenga, “John Holt and the Origins of Contemporary Homeschooling,” http://mhla.org/information/resourcesarticles/holtorigins.htm

[10] Holt, Instead of Education, 38.

[11] Holt, Instead of Education, 218.

[12] Holt ponders whether or not he will have Neil’s “toughness of character” to end life as a nonbeliever or whether he will follow in his father’s footsteps in embracing the belief in an afterlife before he dies. Holt, A Life Worth Living: The Selected Letters of John Holt http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt77-78 [page numbers based on file at hyperlink not physical book published by Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1990.]

[13] Holt, Escape from Childhood: The Needs and Rights of Children (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc, 1974), 47.

[14] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 48.

[15] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 52.

[16] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 18.

[17] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 266-67.

[18] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 267.

[19] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 26-27.

[20] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 27.

[21] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 17

[22], Holt, Escape from Childhood, 28

[23] John Holt, “The Cuteness Syndrome,” Ms. Magazine, March 1974 (Vol. 2. No 9), 77-79, 89-90.

[24] Holt, “Cuteness,” 78.

[25] Holt, “Cuteness,” 78.

[26] Holt, “Cuteness,” 79.

[27] Holt, “Cuteness,” 79. To make his point he told a story of giving a talk in which people heard a child outside of the building get hurt. The adults began to laugh at the triviality of the injury. Holt complains that most adults, like those in his audience, are quick to believe “that the feelings, pains, and passions of children [are] not real, not to be taken seriously.” Had the audience heard an adult get injured the response, claims Holt, would have been very different. “If we had heard outside the building the voice of an adult crying in pain, anger, or sorrow, we would not have smiled or laughed but would have been frozen in wonder and terror.”

[28] Holt, A Life Worth Living: The Selected Letters of John Holt http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt71-72 [page numbers based on file at hyperlink not physical book published by Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1990.]

[29] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 272

[30] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 272

[31] Of all his works this chapter remains one I am the least comfortable with and presently disagree with the most; to his credit, Holt is not dismissive of the complexities of such a debate.

[32]Holt, A Life Worth Living, 72-74 http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt

[33] Holt, A Life Worth Living, 45 http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt

[34] Holt, A Life Worth Living, 77. Letter written April 19, 1972.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt

[35] Holt, A Life Worth Living, 47 http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt

[36] Holt, A Life Worth Living, 46, http://www.scribd.com/doc/235583288/A-Life-Worth-Living-John-Holt

[37] So-called “negative” rights generally associated with libertarianism. Some argue that rights to food, housing, healthcare and the like are “positive” rights. Others, however, dispute such definitions pointing out that most if not all freedoms can be presented as both negative and positive rights. Freedom from violence, for example, requires those wishing to do harm to you to restrain themselves; it further requires others who might not be immediately impacted by violence done to you to intervene, via government, police etc., on your behalf. Thus it could be said that this is also a positive freedom: freedom to be secure in one’s person. The right to food could be said not only to be the freedom to eat but the freedom from starvation. This debate aside, Holt’s political philosophy follows into the category of what is broadly identified as egalitarianism: believing that people are not only entitled to be free from undue interference but also entitled to assistance necessary for a good life.

[38] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 223

[39] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 221

[40] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 221

[41] Holt, Escape from Childhood, 221

[42] Holt, Instead of Education, 207