Below images of Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, and a many-headed hydra consuming humanity, sit two groups. To the right, facing a stage, are approximately 200 delegates of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), seated as a homogenous block. Wearing black ski masks, they furiously take notes. To the left, 300 scientists and observers from throughout the world are seated.

With a tiny pink ribbon pinned to her mask, Julía, a Zapatista delegate from Oventic, Chiapas, takes the microphone: “The rivers are drying up. We know that the people before had a way of planting their crops, but now it doesn’t rain like it’s expected to. Now, there are epidemics that weren’t common before, like cancer and diabetes…”

Julía is unequivocal about the linkages between science and capitalism in perpetuating this crisis. “Medicines just create dependence on the pharmaceutical industry,” she tells us. But Julía is also clear that science can function as a tool of resistance, if reimagined from the grassroots: “Brother and sister scientists, we ask you, according to your studies: why does all this happen? And who is responsible? We have come to hear you and bring this knowledge to the peoples, to our peoples.”

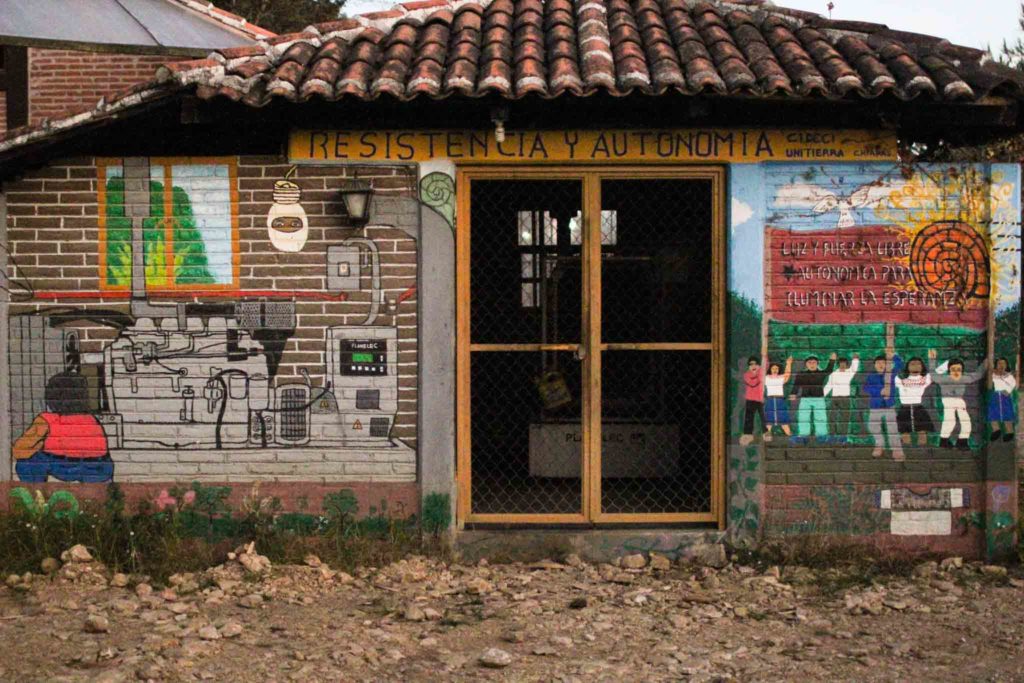

Over four days, from December 27th-30th 2017, the second iteration of ConCiencias, a conference creating dialogue between the Zapatista’s and leading left-wing scientists from throughout the world, took place at CIDECI—Universidad de la Tierra, located on the outskirts of San Cristobal de Las Casas—a city in Chiapas which has long been associated with the Zapatista’s struggle. Although it might seem tangential, the struggle to decolonize knowledge is part and parcel of the Zapatista’s broader project of resisting indigenous genocide, neoliberal capitalism, and political repression.

Las ConCiencias, the title of the conference, brings together the Spanish words for science and awareness. The moniker pinpoints the conference’s dual purpose. First, the Zapatistas convened the meeting to critically explore the ways in which science has historically been a social endeavor largely devoid of consciousness, a project in the service of capital, an endeavor that contributes to the marginalization of indigenous peoples throughout the world. Second, the conference is a space of dialogue to explore the counter-hegemonic potential of science; how can its power be harnessed to identify the cracks in the wall of capitalism, and expand upon them, leading to its dissolution and the resurgent sovereignty of indigenous peoples.

The Zapatista National Liberation Army invited 50 scientists from Europe, North America, and Latin America to present results from their research, and provide insight into how science can be reimagined from, as the Zapatistas say, “below and to the left.” With expertise in topics ranging from geophysics, to optics, to philosophy, and agroecology, the scientists reflected on the Zapatista’s two central questions. First, how can science help in the preparation for the present and coming storm? Second, how can science be reimagined as a tool of resistance that can expand fractures in the wall of capitalism, and its many-headed hydra.

These two guiding questions surround the re-imagination of science—away from an enterprise intertwined with the production of capital—and towards a system of knowledge production that is humanized, which has a transformative social purpose. La tormenta (the storm) is coming. For many small-scale farmers it is already here. This storm is not simply increasing prevalence of storms associated with climate change, but rather the social, ecological, economic, and political contradictions and crises that are interconnected with what grassroots movements are calling “climate chaos.”

How can science function as a method for creating breaks in ‘the wall’ (el muro) of capitalism? How can science enlarge these cracks, undercutting what is hegemonic and allowing for alternative visions of the world to sprout?

As Julía and many other Zapatista delegates asked the amassed scientists: “We need you to speak to others about rebelliousness, and organize where you are, in your neighborhood, in your research center, in your university.”

More than a conference, ConCiencias is a call for scientists to organize, to create new organizational systems for aiding grassroots struggles. Julía implored the scientists: “Don’t exchange truth for lie, and especially not for money. This is what makes you good scientists. We know that you’re great, but we Zapatistas ask you to be even better by working in collectives. Study scientifically, figure out who is responsible for the problems that we have. Who are the really guilty ones? Be the ones who speak with truth, and not in order to get a model. Be honest. This might have consequences of humiliation and threats, but you don’t have to give up because of that. Brother and sister scientists, it’s time to be awake, vigilant, to not lose love for our struggle. We must work everyday to build a collective future.”

Moving from these opening remarks, the delegates from five Zapatista caracoles remarked on the interconnections between exploitation, marginalization, humiliation, eviction, and assassination, and their collective desire and passion for study. The first day included talks surrounding ecology, agroecology, medicine, physics and geophysics, climate change and education.

In the evening, Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano presented a text entitled “It Depends.” Beginning with an argument that this talk would not touch on matters of science, art, or politics, Galeano disentangled the relations between the structural causes of femicide, and the political violence of the Mexican state as epitomized by the 1997 Acteal massacre in Chiapas.

The second day, scientists and Zapatistas reunited to further deepen the analysis of how science can intervene in the context of the crisis of capitalism. Central themes in the presentations included technology, genetics, apiculture, and mathematics. That evening, Subcomandante Galeano returned to present an analysis entitled “Trump, Ockham’s Razor, Schrödinger’s Cat, and the Black Cat” in which he provided a critical case for the need to research capitalism as a systematic series of crimes.

On the third day, questions surrounding critical pedagogy, the cellular constitution of humans, food sovereignty, astronomy, and spectroscopy were major themes. Scientists engaged in critical self-reflection and debated ideas about how to coordinate scientific labor as a form of social mobilization.

At the end of the third, and final day, dozens of Zapatista women took the stage at the front of the auditorium. In the name of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee – General Command of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, they built on the theme of international solidarity developed throughout ConCiencias to invite international female activists to participate in the “First International Political, Artistic, Sports, and Cultural Encounter for Women in Struggle” to be held at the Zapatista Caracol of Morelia in Chiapas, Mexico from March 8-10, 2018. Men are only welcome if they are accompanying a female activist, and will be engaged in solidarity work during the proceedings of the encounter.

Throughout the conference, a major focus was the importance of decolonizing science. Knowledge is not produced in some ethereal space. Rather, it is a political process that takes place in spaces that are imbued with power. Science has long been a force of colonization, which has helped to build up “el muro de capital,” (the wall of capital).

The Zapatistas demand that science be reimagined by both scientists and the grassroots together as a technique of resistance. Decolonizing science requires scientists to organize in their own communities, and to deconstruct how their own research methodologies and epistemologies have been employed as tools of colonialism and neocolonialism. Such a process of decolonization also demands scientists become engaged allies, co-conspirators, and accomplices who can share methodological and theoretical insights with grassroots movements about how to build a new vision of science within the cracks of capital’s wall.

David Meek is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL. His research focuses on the politics of knowledge in grassroots social movements and critical forms of sustainable agriculture education across the world.