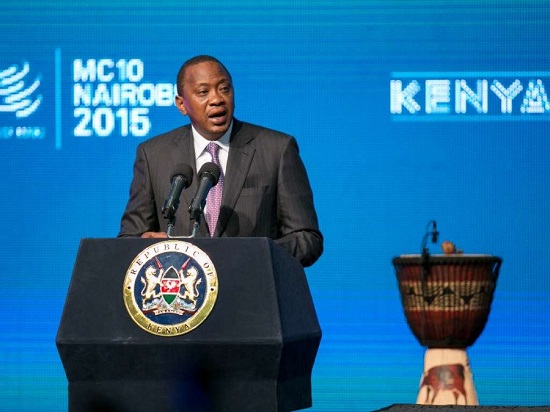

(Photo: Kenyan President Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta)

Source: Pambazuka News

When the World Trade Organization (WTO) met in Seattle, Washington in 1999, the Africa paper[1] carefully prepared by the Kenya representatives to the WTO in Geneva had set the stage for the rejection of the strict intellectual property rights which the Western countries’ pharmaceutical companies desired. Sixteen years later at the 10th WTO Ministerial Conference that was held in Nairobi, Kenya, in December 2015, the United States Trade Representatives had pressured the Kenyan leadership to exclude “African issues” from the agenda while simultaneously pushing through the expansion of the Information Technology Agreement (ITA), which benefits US corporations. That Kenya could be caught in a position where it had to please the United Stated and thus turn its back on India, Indonesia, China and Brazil was an expression of the country’s lack of consultation with Africa and the other countries of the Global South that had been pushing for the Doha Development Agenda. At the end of the meeting, most international media outlets proclaimed the death of the Doha Development Agenda.

Both leaders of the ruling Jubilee party– President Uhuru Kenyatta and Vice President William Ruto – had embarked on a robust diplomatic offensive to escape the status of Kenya as a pariah state after both were indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC). First, there was the seeming rehabilitation of the leadership generated by the visit of President Barack Obama in August 2015, followed by Pope Francis’s visit in November. The 10th WTO Ministerial Conference was supposed to showcase Kenya’s place as a diplomatic and commercial leader in Africa, but instead made Kenya appear naïve and weak. Since the era of plantation economies and trade in human beings when the Spanish Crown established the ‘Asiento’ to the French ‘Exclusive,’ the era of Rule Britannia up to the military management of international commerce by the United States, the Western countries have always had their way when it came to trade. When the WTO was formed there was a lot of buzz about trade liberalization and how the policies of ‘globalization’ would (a) lift the standards of the quality of life of the impoverished billions in the world, (b) lead to full employment, (c) lead to the growth of real income and effective demand and (d) lead to the expansion of production, of trade in goods and services. The opposite has been true, and Thomas Piketty, in his book ‘Capital in the Twenty-first Century’, brought the figures to show how the world had become even more unequal since the era of economic globalization. However, since the formation of the WTO, the political and economic balance in the world has changed. The role of the Global South in global trade and increased South-South trade led by nations such as China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil reflects the more prominent role of developing nations in the world economy.[i]

In Asia, the emerging nations created the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – involving the ten ASEAN plus 6 nations (China, Japan, Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand). In Latin America the cooperation was being routed through Mercosur (The Common Market of the South) while in Africa, the African Union had designated 2017 as the date to realize the Africa Free Trade Area, 2019 for the African Customs Union, 2025 for the African Common Market and 2030 for the African Monetary Union, with the latter finalizing the basis for the establishment of a common African currency. The Kenyan political leadership had paid lip service to the idea of integrating Africa and had pushed ahead with its limited Vision 2030 while rolling out infrastructure projects to reinforce the centralization and concentration of wealth into the hands of a few in Nairobi.

Significantly, this was the first WTO Ministerial Conference to be held in Africa, and in many ways, it was one of those meetings where there could be no agreement on the communique before the meeting because of the intense differences over the refusal of the USA and the EU to agree to former commitments on matters of agriculture and food security for countries such as India. This meeting followed the more than fifteen-year efforts to restore multilateral trade cooperation. Since 2001, there had been negotiations with the former colonized peoples over the future rules in a round of negotiations that had been named after the city of Doha, Qatar. From the moment of those negotiations in November 2001 until today there had been nothing but duplicitous back and forth between the North and the peoples of the South. The designation of these negotiations as the Doha Development Agenda (DDA) has never seriously considered addressing the obstacles placed in the global trading system to foster real trading cooperation which support socioeconomic development in the South. Even while these Doha negotiations were continuing, the United States was involved in new trading arrangements in what was called the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). At the same time, the United States was involved in a collaboration with the European Union to create the TransAtlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). The United States had embarked on the forging of plurilateral agreements.[2] Taken together, these two mega-regionals have changed the multilateral trading system that had been established in 1995 in the form of the World Trade Organization.[ii]

Before the meeting, the representatives of the EU and the US called for the end of the DOHA Round negotiations, saying that because after a decade of negotiations between developed and development nations could not produce an agreement on issue areas defined by developing nations as critical for “development”, the international trade world has moved on and the WTO was becoming irrelevant. If the WTO is not the place for negotiating new rules for global trade which support the economic priorities of developing nations, as was agreed to in Doha when the “development” round was launched, what was the purpose of the 10th Ministerial meeting? Why was Kenya so quick to agree to an agenda leading up to the Ministerial which continued to exclude the “African Issues” before the WTO? The outcome of the meeting and the declaration that was called the Nairobi Package was a slap in the face for the peoples of the South. It was especially egregious that the US used the 10th Ministerial meeting to seek to undermine the future of Pan African trading relations and to drive a wedge between the BRICS societies and those that the US want to manipulate in the Least Developed Countries. Before the meeting the WTO was in a comatose state and this commentary will argue that the 10th Ministerial meeting further hastened the demise of the WTO.

THE WTO IN THE ERA OF BIOTECHNOLOGY AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The WTO was the successor organization to the international platform that had been called the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). GATT had acted as a sister organization to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) to provide a framework for the continued lopsided basis of international economic arrangements. For a brief period after 1973, the energetic forces from the Global South had pushed hard for the implementation of a New International Economic Order (NIEO).[3]

Members of the non-aligned movement had pushed hard in the Uruguay Round 1986-1994 for the poorer nations to play a more central role in international negotiations. This push was sufficiently vigorous to see the technical papers being developed by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the establishment of the UN Centre for Transnational Corporations. The period of rabid neo-liberalism and the scuttling of all discussions of UN reforms limped along with the so-called Uruguay Round of the GATT until the United States, Western Europe and Japan recovered their nerve and pushed through the formation of the World Trade Organization.

The six core areas for the WTO were:

1. an umbrella agreement (the Agreement Establishing the WTO)

2. goods and investment (the Multilateral Agreements on Trade in Goods including the GATT 1994 and the Trade Related Investment Measures, TRIMS);

3. services (General Agreement on Trade in Services, GATS);

4. intellectual property (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, TRIPS);

5. dispute settlement (the Dispute Settlement Understanding, DSU); and

6. review of governments’ trade policies (the Trade Policy Review Mechanism, TPRM).

But from the start of the WTO, the questions of Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights and Public Health became burning issues, especially in the face of the massive deaths from HIV/ AIDS. The staid language that was presented on the goals of the WTO was an effort to neutralize the burning issues of bio-piracy that had emerged in the era of bio-technology and information technology. Representatives from the Global South objected to the push by the Northern corporates to isolate, identify, and recombine genes and in the process making the gene pool available as a raw source for future economic activity by the big pharmaceutical companies. The Western corporations had argued that life can be made, life could be owned and the book ‘The Biotech Century’ by Jeremy Rifkin had outlined how the awarding of patents on genes, cell lines, genetically-engineered tissue, organs, and organisms, was giving the marketplace the commercial incentive to exploit the new resources. It was in this period of what Vandana Shiva called Biopiracy when the term “Globalization” was deployed to diminish the calls for economic sovereignty in the Third World. Under the rules of the WTO, the globalization of commerce and trade enabled the wholesale reseeding of the Earth’s biosphere with an artificially produced bio-industrial nature designed to replace nature’s own evolutionary scheme.

AFRICANS FIGHT BACK

Using the platforms of the United Nations and the battles over the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a common position was developed in Africa with respect to TRIPS and the patenting of life forms. At the Seattle meeting in 1999, the common African position written by the Kenyan delegation had fought to oppose the establishment of property rights over community held resources, traditions, practices and information. Prior to the meetings in Seattle in 1999, the Africa group had produced a very detailed and clear position on why the direction of the WTO was undermining food security in Africa and posed a threat to the future of agriculture in Africa. From the start of the WTO to this day it was the position of the Africa group that at the core of the TRIPS legal framework was a threat to the societal values and interests of the peoples of the South.

The energetic work of these progressive forces had informed the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in crafting Model Legislation for the protection of the Rights of Local Communities, Farmers and Breeders, and for the regulation of access to biological resources. The technical language of this legislation was adopted by the OAU in Algiers in 2000 and later reaffirmed as a founding document of the African Union. For the meeting in Doha in 2001, this African position was reaffirmed in the document, AFRICA GROUP PROPOSALS ON TRIPS FOR WTO MINISTERIAL. Inter alia, this document restated the position that,

“With regard to the protection of plant varieties, the TRIPS Council shall clarify that Members have the right to determine the appropriate sui generis system for the protection of plant varieties that is best suited to their interests. The implementation of this provision shall not prevent developing country Members from implementing sui generis systems that accord due recognition to farmers and local communities for their traditional knowledge, ensure food security and safeguard farmers’ livelihoods. Such sui generis systems shall also not undermine traditional farming practices, including the right of farmers to save, use, exchange and sell seeds, as well as, to sell their harvest. We further agree that the transition period for the implementation of Article 27.3(b) shall be extended for a further five years from the date its review is satisfactorily completed.”

When the African Union was formed in 2002, the basic position on TRIPS and the efforts to protect African farmers were retained with the AU reaffirming the sovereign rights of states over natural resources. The Africa position had been very influential in the mobilization of the countries of the Global South for the Doha negotiations. The Africa position on TRIPS turned out to be one of the troublesome issues of the Doha Development round. The AU also reaffirmed the “African Convention on the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resource.”[iii] In order to push ahead with its attempt to empower the pharmaceuticals and the seed companies, the EU and the USA offered trading agreements with Africans and in the WTO set aside the discussions under the umbrella of special safeguard mechanism (SSM) while pushing ahead with efforts to “invade” the most rural areas of the planet with bioprospectors and bioanthropologists. By the time the US had established the Human Cognome Project to advance the study of artificial intelligence, the trade representatives of the OECD were no longer interested in the Convention on Biological Diversity or treaties to preserve indigenous knowledge.

WTO AND PSEUDO-DEMOCRATIC DECISION MAKING

When the WTO was formed in 1995, it was supposed to be an international body embracing all of the countries of the world that subscribed to the ideas of free and unhindered trade. Unlike the IMF, where the OECD countries dominated, the WTO was supposed to be the final arbiter in trade disputes where all decisions were in principle to be made by consensus. This decision by consensus belied the strategy of decision making in the ‘green room’[4] or the closed door meetings that were called by the Director-General. From its inception, the Director-General of the WTO has been a supporter of neo-liberalism. As the WTO says of itself, “the World Trade Organization (WTO) is the only international organization dealing with the global rules of trade between nations. Its main function is to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible.”

This language had been agreed to in public but from 1995 until this point of the 10th Ministerial Meetings, the leaders of the United States and the European Union sought to bully, cajole and sabotage efforts to develop equitable international trade. Intellectuals (such as the late Norman Girvan, Martin Khor, Samir Amin and Yash Tandon) working through institutions such as the South Centre (in Geneva) and from the Third World Network (TWN) had been active in the negotiations and rightly argued that there can be no equitable trade without reforming the international financial architecture of the Bretton Woods system. Scholars such as Samir Amin had opposed the neo-liberal position of the USA and the role of the dollar in international trade and finance. The exorbitant privilege of the US dollar came under even greater scrutiny after the 2008 financial crisis when the USA proceeded to print dollars under the policy of quantitative easing, adding about US$4 trillion to the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve. The distortions of trade were reinforced by the distortions of financialization in so far as trade follows finance and the USA and the EU as creditors and holders of the dominant reserve currency status could always call the shots.

The combined powers of the European Union, the United States along with their domination of trade and finance via the dollar and the Euro had inspired greater cooperation among the poorer nations, with countries in Latin America seeking ways to trade outside of the dollar. The countries of the ASEAN nations had also embarked on new trading practices to elude the possibility of strengthening the US dollar. It was not by accident that at the UNCTAD meeting in Accra, Ghana, in 2008 it was reaffirmed that the structural adjustment policies of the IMF hindered real transformation of the economies of the Global South. Scholars of the non-aligned world had been active in opposing the structural adjustment packages of the neoliberal policies that maintained the status quo of the Bretton Woods financial architecture, which extols privatization alongside liberalization and stabilization. The Accra Accord of UNCTAD in April 2008 comprised of text on four sub-themes: (1) enhancing coherence in global policy making, (2) trade and development issues, (3) enhancing the enabling environment to strengthen productive capacity; and (4) strengthening UNCTAD. The US and Europe were always against the strengthening of UNCTAD. The OECD states were jealous of the fact that UNCTAD had provided the kind of technical assistance necessary for the countries of the South to challenge the high-flying intellectual property rights lawyers of London, Paris, and New York.

In the book, ‘The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South’, Vijay Prashad outlined the delicate negotiations that had taken place between 2001 – 2012 over the question of what was eventually called the Doha Mandate. This was the position of the Global South that trade must support inclusive and innovative economic change, that trade could not be divorced from finance and that the state had to play a central role. The Doha Mandate stated clearly that,

“The State has the primary responsibility for its own economic and social development and national development efforts need to be supported by an enabling international economic environment. The state, having an important role to play, working with private non –profit and other stakeholders, can help forge a coherent development strategy and provide an enabling environment for productive economic activity.” (Paragraph 12, Doha Mandate)

The important aspect about the Doha negotiations since 2001 was that the Global South had been able to maintain a firm and united position in the face of the multiple plans that had been unleashed by the Global North to divide the peoples of the Global South. Throughout the period since Seattle, it was the working understanding of the peoples of the South that the international framework for economic policy had to be people-centered. From the perspective of the North, the framework for international economic policies should be centered on international finance and the profitability of the financial moguls and multinational corporations.

Faced with the levels of organizing by the progressive members of the Group of 77, from the outset, the Northern corporations had sought to weaken the solidarity among the poorer nations by creating a division between the ’emerging nations’ (such as Malaysia, Mexico, India, China, Brazil) and the Least Developed Nations. This divide and rule strategy had been first orchestrated after the 1973 oil crisis when Henry Kissinger sought to divide countries such as Algeria, Venezuela and Brazil on one side from Bangladesh, Haiti, Tanzania, Mozambique, Angola, Ethiopia and Zambia, on the other. In 2015, to be a member of the LDC is to be judged to be a state where the per capita income was below US $1,035. In 1997, the WTO had established a high-level meeting on trade initiatives and technical assistance for the LDCs to create for them an ‘integrated framework’ involving six intergovernmental agencies to ‘help least-developed countries increase their ability to trade, and some additional preferential market access agreements.’ However, in 1999, opposition from the labor organizations in the US that opposed NAFTA had aligned with the NGOs from the South and firm leaders of the LDC that opposed bio-piracy. The environmental lobby had also emerged as a major political force, especially after the climate talks in Copenhagen in 2009 where there was the insistence that trade must consider the impact of global warming.

THE ALLIANCE OF PROGRESSIVES, NORTH AND SOUTH

The South Centre in Geneva and the Third World Network had created a strong platform to expose the duplicitous positions that were being pushed by the transnational corporations from the North. The most egregious example was over the question of the manufacturing and trade of generic drugs in the midst of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Kenya had been the playground of the pharmaceutical companies, and the fictional novel ‘The Constant Gardener’ revealed the complicity of the Kenyan leadership in allowing western pharmaceutical companies to use the Kenyan poor as guinea pigs. Since that novel, the author John Le Carré has said that the truth (about using pregnant African women as guinea pigs for drugs testing) was even scarier than his fictive rendition. Since that time there has been studies that highlighted the fact that clinical trials were now an industry in Kenya. (See The Clinical Trials Industry in Kenya). While Kenya was violating its own undertakings about public health before the WTO, India, South Africa and Brazil formed a bloc of countries that worked hard to provide generic therapies for the poor. The role of Al Gore and Bill Clinton in fronting for US corporations in the case against Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) in South Africa now ranks high in the hall of infamy.

AGRICULTURE AS THE ACHILLES HEEL OF THE WTO

Many younger readers will not remember that while the IMF and the World Bank were urging African countries to remove all agricultural subsidies, the subsidies paid to farmers in the state of Iowa (in the USA) were more than the entire subsidies provided by all of the African governments for their farmers. It has been estimated that the USA subsidized farmers to the tune of $41 billion every year. Secondly, through the Common Agricultural Policies (CAP), the EU provides massive subsidies to the farmers of Europe. That subsidy is estimated to be about $86 billion per year. If the WTO is to be democratic, the removal of agricultural subsidies across the board must be a major issue.

The key question about international trade that has been on the negotiating table for decades was whether the agricultural subsidies provided to European farmers (CAP) comprised unfair competition. Samir Amin in the book ‘The Liberal Virus: Permanent War and the Americanization of the World’ argued that the property rights regime and forms of agricultural production in the EU and North America threatened the very existence of the oppressed of the Third World.

“We are thus at the point where in order to open up a new field for the expansion of capital (modernization of agricultural production) it would be necessary to destroy – in human terms – entire societies. Twenty million efficient producers (fifty million human beings including their families) on one side and five billion excluded on the other. The constructive dimension of this operation represents no more than one drop of water in the ocean of destruction that it requires. I can only conclude that capitalism has entered its declining senile phase; the logic which governs the system is no longer able to assure the simple survival of half of humanity. Capitalism has become barbaric, directly calling for genocide. It is now more necessary than ever to substitute for it other logics of development with a superior rationality.”[iv]

For two decades the question of agricultural subsidies was front and center of the negotiations of the WTO where the countries from the South argued that it was the obligation of governments to provide cheap food to the most vulnerable sections of the population at very low prices. The previous two Ministerial meetings of the WTO had been debating the position of India where the Indian government was stockpiling food and providing subsidies to the consumers through the public distribution system. Apart from providing subsidies to the consumers, the government of India also provided subsidies to the producers of food grains. The Indian government buys food grains from farmers at a minimum support price and subsidizes inputs like electricity and fertilizer.

The 9th Ministerial meeting in Bali, Indonesia (2013) had ended without agreement because India wanted a permanent solution to the issue of public stock holding of food grains. The G-33 members including China have supported India’s stand on the ability to subsidize agricultural production and distribute it to the poor at low cost. The OECD countries wanted India to open up its own stockpile to international monitoring. Indian diplomatic overtures within the corridors of BRICS and in the India-Africa summit have been to maintain that the question of food security for the poor remain a central pillar of the Doha Development Agenda. At the Third India-Africa summit in Delhi in India, in October 2015 prior to the 10th Ministerial meeting the Prime Minister of India had said,

“We should also achieve a permanent solution on public stock-holding for food security and special safeguard mechanism in agriculture for the developing countries.”

The US and the Europeans have worked diligently to come out with backroom deals and agreements such as the US Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) or the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) that were meant to hinder real cooperation among Africans. Backroom and back door deals, undermining the technical capabilities of African negotiating teams and outright bribery, were the preferred tools of the West. More importantly, the most profitable aspect of the trade between the United Sates and Africa was in armaments. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), arms sales from the USA to Africa grew faster than any other region of the world 2005-2014. AGOA and the US Africa Command were two sides of the US engagement with Africa.

This is not the place to offer a detailed critique of the AGOA policies that allowed certain goods from Africa to enter the US market duty free. Suffice to say that after fifteen years, this trading agreement between the USA and African countries did not change the status quo where the bulk of African trade with the USA comprised of petroleum products, minerals, and commodities such as tea, coffee and cocoa. A few states were able to produce textiles and export to the US market but the most important engagement of the USA with Africa was via the military. This military relationship, which has deepened under the guise of the global war on terror, ensured that the trade negotiators always had a route to bully leaders of Africa. There has been more than one occasion where African Trade representatives were holding the line of the Global South at meetings only to be told that they must change their position or the US Trade Administrator would ensure that there was a call from Washington to the Head of State.

After several rounds of talks, the language that was worked out was that instead of writing into the WTO that there should be total elimination of export subsidies, the US would agree to language where forms of subsidization were to be defined as “legal-non trade distorting” or “illegal-trade distorting” and the former were to be gradually eliminated over time. This compromise was worked out so that the US could get the support of the EU on creating a WTO working group on bio-technology and genetically-engineered foods. Genetic-engineering companies such as Monsanto are at the forefront of pursuing an agenda of globalization to be able to promote the interests of American agribusiness. Twenty years after the formation of the WTO, the leaders of the EU and the US have not only refused to budge on the question of the billions they spend annually on agricultural subsidies, but they have also sought to dictate and define as “illegal” what ways poorer countries such as India could provide support for their farmers in order guarantee a level of food security for their peoples.

THE DOHA DEVELOPMENT AGENDA

Because trade cannot be separated from reality, this process of negotiations since Seattle in 1999 had to deal with the consequences of the global war on terror, the capitalist depression after 2008 and the current efforts by the US to create an alternative platform for the domination of the world economy by US-based multinational corporations. The first Ministerial meeting after Seattle had taken place in Qatar a few weeks after the major World Conference Against Racism (WCAR) in Durban, South Africa. It was in Durban where the Caribbean and the Latin American states mobilized international public opinion to demand that current trade arrangements acknowledge past crimes against humanity, especially the trading systems of the Transatlantic slavery, colonial trade and the lopsided nature of the international financial system. In Durban, as in Seattle, the United States and the European Union made it clear that the international meetings held under the auspices of the UN or the WTO were to serve the interests of US corporations.

In 1999, at the WTO meeting in Seattle, the United States had promised that the subsequent meetings of the WTO would focus on issues that were of primary importance to the former colonial territories that were grouped in the Group of 77. A WTO committee on trade and development, assisted by a sub-committee on least-developed countries was mandated to examine the special needs of ‘developing countries.’ The responsibility of this Special Committee included implementation of the agreements, technical cooperation, and the increased participation of developing countries in the global trading system.

One important aspect of this Development Committee was that all WTO agreements contain special provision for developing countries, including longer time periods to implement agreements and commitments, measures to increase their trading opportunities and support to help them build the infrastructure for WTO work, handle disputes, and implement technical standards.

By the date of the November Ministerial meeting of the WTO at Doha, the discussion about the repair of the world trading system was quickly overshadowed by the events of the major attack on the World Trade Center in New York City on September 11, 2001. That gathering was significant because prior to the meeting, the US had argued that in the face of a health crisis emanating from anthrax attacks, the USA could override the patent rights of the German manufacturer of the drugs that to treat those affected by the anthrax attacks. According to the WTO’s Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), member countries are required to recognise international patents on medicine. However, the rules also say that “this requirement may be waived by a member in the case of a national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency”. In waiving the Bayer patent, the US would be able to approach other companies to manufacture greater and cheaper supplies of ciprofloxacin, as the drug is known generically. African states and India and Brazil had paid special attention to the double standards and hypocrisy of the trade representatives of the USA.

By the time the WTO Fourth Ministerial Conference was held in Doha, Qatar, in November 2001, the representatives of the USA declared at that meeting that it was necessary to reconsider the demands of Seattle in light of the fact that the United States was now involved in a war on terror. The US trade representative carried the George Bush line to the meeting that it was necessary for the world to support the United States. The favored line was, “You are either with us or against us.” As a sop to the states that had been arguing for a New International Economic Order, the European states and the United States promised to start a Development Round to address issues of improving living standards for the poorer societies.

According to the official web platform of the WTO, the aim of the Doha Round was “to achieve major reform of the international trading system through the introduction of lower trade barriers and revised trade rules. The work programme covers about 20 areas of trade.” The Round is also known semi-officially as the Doha Development Agenda whose fundamental objective is to improve the trading prospects of developing countries.

The Doha Ministerial Declaration provided the mandate for the negotiations, including on agriculture, services and an intellectual property topic, which began earlier. Yash Tandon in the book, ‘Trade is War: the West’s War against the World’ has traced in great detail the duplicity of the West and the strong arm tactics that have been used over the past fifteen years to block real negotiations while pressuring the poorer nations into Economic Partnership Agreements which in reality do little more than finance (via debt) sustainability of a low level equilibrium of poverty and underdevelopment.

EMERGENCE OF THE SOUTH: RCEP AND MERCOSUR

While the West dithered on the rules of international trade and commerce, the axis of the world economy was slowly shifting to Asia and Africa. In 2012, the 10 countries of the ASEAN nations along with China, Japan and South Korea established the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). RCEP includes more than 3 billion people, has a combined GDP of about $17 trillion, and accounts for about 40 percent of world trade. In Latin America there was the emergence of Mercosur, but the real change in the global trade and commerce was the formation of the BRICS countries after the global financial crisis of 2008. Vijay Prashad summed up the importance of BRICS in the international trading system in this way:

“The BRICS bloc is a demographic powerhouse – it constitutes 40 percent of the world’s population and sprawls over 25 percent of the world’s landmass. Of the total world GDP, the BRICS produces a quarter. The five countries in the bloc are divided by culture –language, religion, and social mores. They are also differentiated by their economic trajectories –some of the states are governed by the logic of export oriented industrial production, while others are reliant upon raw material export. Such differences, however, do not reduce the political value of the bloc. In conventional terms, these are not minor states –three of the five are declared nuclear powers, two hold permanent seats on the UN Security Council and two others are aspirants for such seats. They have created, thus far, a multilateral platform. Their ambition is to use their combined weight as a counter balance to the habit of Northern primacy and as a forum to raise issues and analyses that are not able to rise to the surface. Assertion in the realm of intractable political arenas (even the Palestine-Israel conflict) and into the debate on financial reform as well as development strategy marks the BRICS attempt to make its presence felt on the world stage as a political platform.

But this level of assertion is constrained by hesitancy amongst the leadership of the states of the BRICS –they are uneasy with any challenge to the North. They prefer to operate passively, building trade relations amongst their countries, and with the potential BRICS Bank, forging a development program for the South that will rotate around their own growth agendas. There is no frontal challenge to Northern institutional hegemony or to the neo-liberal policy framework. BRICS, as of now, is a conservative attempt by the Southern powerhouses to earn themselves what they see as their rightful place on the world stage.”

It was this alliance between the Global South that had pushed the Doha Mandate and held the West to this mandate up to the 9th Ministerial meeting of the WTO in Bali, Indonesia. Faced with the cohesion of the BRICS nations in the negotiations over the future of the international trade, the United States moved to create new trading platforms such as the TPP and the TTIP. Inside the WTO, the USA sought to establish what it termed ‘plurilateral agreements’ with a minority of likeminded states. While negotiating these new trade agreements behind the backs of even the citizens and law makers in the USA, the Ministerial meetings of the WTO became deadlocked and this was the case for the 9th Ministerial meeting at Bali in Indonesia (2013).

Old questions of intellectual property and the patenting of life forms proved contentious along with the permanent question of the massive agricultural subsidies paid to farmers in the United States and the European Union. Because agriculture remains the lifeblood of the South, the challenges from the poorer nations on the question of food subsidies permanently threatened the WTO. African trade officials had fought the USA over the trade distorting cotton subsidies and the African Cotton-4 ( Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mali ) had rallied the African Union and had brought out the fact that the USA ignored the rules of international trade when it related to questions of subsidies for US companies and farmers. Future work will outline the relationships between the US counter terror operations in Mali and Burkina Faso and the US support for the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) to divert African energies from carrying forward the legal and political claims of African cotton producers. The USA understood the potency of the Cotton-4 in Africa in so far as the Africans in Africa could have joined forces with African Americans who have been continuously disadvantaged by the subsidies to agribusiness and the impact of the US Farm Bill on Africans in the USA. The question of US agricultural subsidies had touched on one of the most sensitive aspects of the US defense policies.

Countries such as India had created a solid bloc with Africa to oppose the double standards of the West and at the Bali Ministerial meeting, India had worked hard to ensure that it would be granted a permanent food security waiver to stockpile food as a hedge against famine and hunger. The Bali declaration had covered four broad areas: ‘trade facilitation,’ agriculture, cotton, and the LDC issues. The Bali communique was remarkable in its cover-up of the inconclusive treatment of agricultural subsidies. From 2013 to the time of the Nairobi meeting, the push of the North was to seduce the so-called LDCs with promises of market access and to break the solidarity between the Global South. One major argument was that countries of BRICS such as India, Brazil and China should no longer be classified as developing areas.

THE KENYAN TRAP

The levels of capital accumulation in Kenya had reached the point where Kenya could boast as a society with African billionaires. Kenya had achieved a level of economic diversification with the top capitalists exploding in telecommunications, banking, real estate, light manufacturing, beside the older forms of wealth creation in tourism, import substitution industries, plantation agriculture, growing flowers and transportation. The wealth of the ruling class was sufficient to lift Kenya out of the group of Least Developed Countries. When the Pope visited Kenya in November 2015, he was not shy to distance himself from the political leaders of Kenya proclaiming that the exploitation of the poor was a “new forms of colonialism” that exacerbate the “dreadful injustice of urban exclusion.” Pope Francis while speaking in one of the well-known poorer neighborhoods of Nairobi had stated,

“I am here because I want you to know that I am not indifferent to your joys and hopes, your troubles and your sorrows. I realise the difficulties which you experience daily. How can I not denounce the injustices which you suffer?”

He continued by stating that such were the result of “wounds inflicted by minorities who cling to power and wealth, who selfishly squander while a growing majority is forced to flee to abandoned, filthy and rundown peripheries.” There was no double-speak here. Here was a clear statement on politicians who used power to enrich themselves.

In order to maintain economic and political power, violence in the electoral process had brought Kenya to the front of the international attention after 2008. It was after this post-election violence when the current President and Deputy President were indicted before the International Criminal Court. In the face of this indictment, Kenya developed a look-East policy and deepened its relationship with countries such as India, China and Iran. For two years after the elections of 2013 in Kenya, the public diplomacy of the leadership was to win friends and allies at the African Union and in the Group of 77. It was in this period of intense diplomacy when Kenya was chosen as the site for the 10th Ministerial Meeting. But, the leaders of the USA and the EU did not sit quietly. As soon as it was clear that the political leaders in the Kenya political system were unprincipled, the western diplomats went to work. The Obama visit to Kenya and the inclusion of Kenya in the Power Africa project was one indication of the pressures on the Kenyan leadership. After the Global Entrepreneurship Conference in August 2015, various US transnationals such as IBM, Facebook, Starbucks and General Electric announced that they would open up new facilities in Nairobi. From Europe, it was made clear to the Kenyan exporters of flowers that if Kenya supported India and the so-called Doha Agenda, the floral business could be in trouble. Placing Kenya on the list of countries where European tourists should not travel was another weapon. Prior to the 10th Ministerial meeting, the government of France announced that it was safe for French tourists to travel to the Kenyan coast.

This kind of diplomacy set the stage for the 10th Ministerial meeting in Nairobi where before the meeting the USA made it clear that this meeting would drop the Doha development issues and the so-called Africa Issues. The US delegation had dictated to the Kenyans that the Doha Development Agenda should be kept out of the meeting and the political leadership of Kenya did not put up any resistance because, to them, their future before the ICC was more important than the welfare of over 3 billion citizens of the Global South who suffer from the unfair trading practices of the Global North.

THE WTO IS COMATOSE

Faced with the growth of BRICS and the RCEP, the United States went about the creation of a new trading initiative called the Trans Pacific Partnership. The TPP Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) groups the U.S., Canada and Mexico with Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Another preferential trade agreement is also being negotiated between the EU and the USA in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). These two agreements are being built to strengthen the position of global capital and create an alternative institutional power base for big US capital within the system of multilateral trade and international law. What is significant about these two agreements is that they both exclude India, Brazil, Indonesia and China. What the leaders of the USA and Europe have not grasped is the reality that trade wars and currency wars could not be divorced from the current capitalist recession. Working peoples all over the world are opposed to secret negotiations of the type that produced the TPP and it is in the midst of this crisis where the USA and the EU are placing the nails in the coffin of the WTO. Kenyan small farmers and Kenyan workers have been agitating for better living conditions and the 10th Ministerial meeting was held in Kenya during a period of a long drawn out industrial dispute over wages with the teachers of Kenya. All over the world workers are agitating for better conditions and in Africa worker militancy have risen in countries such as Ethiopia, Nigeria and Egypt. The textile workers of Egypt were the backbone of the uprisings in Egypt that toppled Hosni Mubarak.

The Nairobi Ministerial meeting was a clear example of how a weakened political leadership could capitulate before global capital to save their own interests, but the contradictions between the rich and the poor that Pope Francis addressed in Nairobi will have to be fought out long after the delegates have left Kenya. This struggle in the WTO is part of the wider struggle for the rights of working peoples.

The representatives of workers in the USA in the Labor Advisory Committee on Trade Negotiations and Trade Policy (LAC) have come out clearly against the secretive and anti-worker position of the TPP, declaring:

“On behalf of the millions of working people we represent, we believe that the TPP is unbalanced in its provisions, skewing benefits to economic elites while leaving workers to bear the brunt of the TPP’s downside. The TPP is likely to harm the U.S. economy, cost jobs, and lower wages.

The primary measure of the success of our trade policies should be increasing jobs, rising wages, and broadly shared prosperity, not higher corporate profits and increased offshoring of America’s jobs and productive capacity. Trade rules that enhance the already formidable economic and political power of global corporations—including investor-to-state dispute settlement, excessive monopoly rights for pharmaceutical products, and deregulatory financial services and sanitary and phytosanitary rules—will continue to undermine worker bargaining power, here and abroad, as well as weaken democratic processes and regulatory capacity across all 12 TPP countries.”

This clear statement is a reminder of the period before Seattle in 1999 when the workers in the USA who opposed NAFTA had joined forces with activists from the Global South. Kenya is now caught in a trap of its own making. At the 2015 Meeting in Nairobi, it was announced that there was Agreement on Landmark Expansion of Information Technology Agreement. This is the first major tariff-elimination deal at the WTO in 18 years. The US gloated that it had achieved its objective, but such shortsightedness cannot change the realities on the ground in Africa as this agreement (the ITA) was never defined by developing nations as one their priorities for the Doha Development Round.

Currently trade between African countries has been at about 10-12 per cent for decades. African trade comprises only 2 per cent of World Trade. Despite the high sounding words of the Millennium Development Goals and the new SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals), the reality on the ground among the most oppressed was that market fundamentalism strengthened the political and economic power of the West. The EPA and AGOA agreements have been signed to keep African trade low, but the massive explosion of people-centered economic activities is creating a dynamic that is independent of governments such as that of Kenya.

The 10th Ministerial meeting ended by punting the delicate questions of food security and a communique published by the WTO called the Kenya Package again signaled the postponement of the ‘Africa Issues’ that had been on the table as the Doha Development Agenda since 2001. Of the four major outcomes of the meeting, the one takeaway was the International Telecommunications Agreement which suited the banks and telecoms sector of the West. The other three were the agreement on Trade facilitation, postponing the issues of food security until 2017 and giving the least developed countries more time to fulfill their obligations under TRIPS. In short, the USA failed to respond to the questions posed by poor African farmers and international NGOs decried the fact that the Kenyan government allowed the USA to undermine the collective positions of the Global South. One Nepalese activist said, “Africa is being marginalised on the very soil of Africa. A likely outcome of this non-transparent process would devastate Africa’s economy and policy space. This will create massive unemployment in Africa, especially for youth and women. It will dispossess millions of people of their livelihoods and become internal refugees in Africa, and easily half a million people potential refugees heading for Europe no matter what the obstacle.”

Despite the betrayal by the Kenyan leaders, one of the widely read newspapers of Nairobi, the East African, carried the headline: “Surprise win for Africa as it gains greater market access globally.” To complement this spin, the WTO itself put out a statement to declare that “The Nairobi Package contains a series of six Ministerial Decisions on agriculture, cotton and issues related to least-developed countries. These include a commitment to abolish export subsidies for farm exports, which Director-General Roberto Azevêdo hailed as the “most significant outcome on agriculture” in the organization’s 20-year history.[v]

So here was the U.S. spin. US could not hide the fact that everything completed were on topics of interest to the north, even as they spin it as also good for developing nations. The statement on the meeting from the US Trade Representative was telling that the U.S. Corporate group said it was disappointed that every element of the Doha round was not killed permanently but that the USA was able to create a wedge between some African members and other members of BRICS.

“It’s fitting that our work in Nairobi delivered a meaningful package that will aid development around the world. With the help of African countries and other Least Developed Countries, we were able to design new rules and disciplines for export subsidies, export credits, state trading enterprises and food aid.”[vi]

In their public declarations since the end of the meeting, the US government says that the Doha round can continue but that WTO members are now free to propose new issues be introduced. This will further remove chance of addressing issues of importance to the global south as promised under the Doha round.

Agenda 2063 of the African Union has placed clear goals of intra-African trade and the transformation of the African economies. In 1977 the Kenyan leadership had conspired with the West to destroy the East African Community. During the long-standing wars against the peoples of Somalia, Kenya was the base for western intelligence forces and for the fundamentalists that financially supported jihadists in Somalia. In order to enrich themselves, the Kenyan political elites instigated post-election violence to terrorize Kenyans while the same political leaders postured as guardians of African independence. The WTO ministerial meeting was the opportunity for Kenya to show that it was truly independent, but the leaders succumbed to the pressures of the EU and the USA, even while seeking better trade relations with India and China. The political leadership of Kenya turned their backs on the agreements of the Global South in order to curry favor with the West. History will be a harsh judge on the role of Kenyan leaders in the 10th Ministerial meeting of the WTO.

Policy makers from the Groups of 77 have noted that continuing the round of WTO talks until 2017 will give the US and EU more time to try and conclude and bring into force TPP and TTIP trade agreements. If that happens, both will indicate that these agreements are the new norms in international trade rules and in order for the WTO to be relevant in the 21st century it must follow the same direction. Of course neither agreement addresses issues or the positions of the Global South that were supposed to be part of the Doha development round. More importantly, the US establishments have the false confidence that the international political and economic system will remain the same until 2017.

Ultimately it will be up to the Global South to strategically determine if the WTO can be a location to establish trade rules which actually support transformation and development or if, just as we’ve seen with the BRICS, alternative institutions and frameworks need to be developed.

* Horace G. Campbell is Professor of African American Studies and Political Science at Syracuse University. He is also a Special invited Professor at Tsinghua University, Beijing. He is recently the author of the book, ‘Global NATO and the catastrophic failure in Libya’.

END NOTES

[i] The concept of the Global South is used in this paper to represent the formerly colonised societies that came out of the Bandung Process and formed the nonaligned nations. The Global South comprised of underdeveloped countries of Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America. Today, these societies are increasingly working together with China and Russia who, though not formally members of the South have worked in the BRICS formation to align with the members of the former nonaligned nations. For an analysis of the evolution of this group that is called the Global South, see Vijay Prashad, The Poorer Nations: A Possible History of the Global South, Verso Books, New York, 2012.

[ii] For two different understandings of the role of the WTO see (a) Peter Van den Bossche, The Law and Policy of the World Trade Organization: Text, Cases and Materials, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., 2006 and (b) Yash Tandon, Trade is War: the West’s War against the World, OR books 2006

[iii] For the position of the African Union on the Model Legislation and the support for the rights of African farmers see here.

[iv] Samir Amin, The Liberal Virus: Permanent War and the Americanization of the World, Monthly Review Press, New York 2004.

[v] “WTO members secure “historic” Nairobi Package for Africa and the world, “https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news15_e/mc10_19dec15_e.htm

[vi] Statement by Ambassador Michael Froman at the Conclusion of the 10th World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference, published in the Nelson Report, December 20, 2015. For the editorial position of the New York Times, see, “Global Trade after the Failure of the Doha round,” http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/01/opinion/global-trade-after-the-failure-of-the-doha-round.html?_r=0 For an alternative viewpoint see, “Imperialism’s New Trade negotiating Strategy.”

[1] The proposals were formulated as “AFRICA GROUP PROPOSALS ON TRIPS FOR WTO MINISTERIAL” and presented by Kenya on behalf of the OAU. A similar paper was presented by Zimbabwe on behalf of the OAU to the Doha Ministerial meeting in 2001.

[2] A plurilateral agreement is a multi-national legal or trade agreement between countries. In economic jargon, it is an agreement between more than two countries. Both TPP and TTIP are referred to as plurilateral agreements within the framework of the WTO.

[3] The idea of the New International Economic Order was articulated in the 1970s by the underdeveloped countries, through the platform of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), and sought the restructuring of the international order with the goal of creating greater equity for developing countries on a wide range of trade, financial, commodity, and debt-related issues.