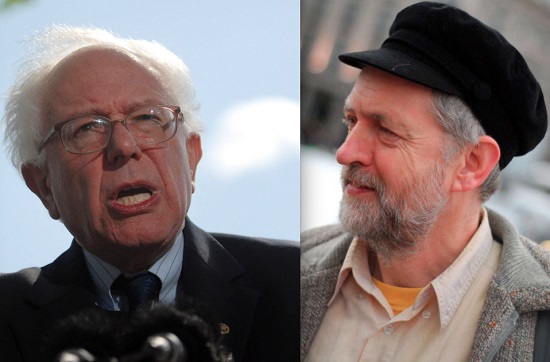

The sweeping triumph on September 24 of Jeremy Corbyn to be the leader of Great Britain’s Labour Party was stunning and totally unexpected. He entered the race with barely enough support to be put on the ballot. He ran on an uncompromisingly left platform. And then, standing against three more conventional candidates, he won 59.5% of the vote in an election that had an unusually high turnout of 76 percent.

Immediately, the pundits and the press opined that his leadership and platform guaranteed that the Conservative Party would win the next election. Is this so sure? Or does Corbyn’s performance indicate a resurgence of the left? And if it does, is this true only of Great Britain?

Whether the world political scene is moving rightward or leftward is a favorite subject of political discussion. One of the problems with this discussion has always been that the direction of political trends is usually measured by the strength of the extreme position on the left or the right in any given election. This is however to miss the essential point about electoral politics in countries with parliamentary systems built around swings between center-left and center-right parties.

The first thing to remember is that there is a large gamut of possible positions at any given moment in any given place. Symbolically, let us say they vary from 1 to 10 on a left-right axis. If parties or political leaders move from 2-3, 5-6, or 8-9, this measures a swing to the right. And reverse numbers (9-8, 6-5, 3-2) measure a swing to the left.

Using this kind of measurement, the last year has seen a striking shift to the left worldwide. There are a number of clear signs of this shift. One is the steadily rising strength of Bernie Sanders in the race for the U.S. presidential nomination in the Democratic Party. It doesn’t mean that he will defeat Hillary Clinton. It does mean that, to counter the poll ratings of Sanders, Clinton has had to assert more leftward positions.

Look at a similar event in Australia. The right-wing party now in power, the Liberal Party, on September 15 ousted Tony Abbott as its leader. Abbott was known for his acute skepticism on climate change and his very tough line on immigration to Australia. Abbott was replaced by Malcolm Turnbull, who is considered somewhat more open on these questions. Similarly, the British Conservative Party has softened its austerity proposals to win over potential Corbyn voters. These are shifts from 9-8.

In Spain, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy of the conservative New Democracy Party is facing rising poll figures from Pablo Iglesias of Podemos, running on an anti-austerity platform similar to what was long promoted by Greece’s Syriza Party. New Democracy did quite badly in the May 24 local and regional elections. Rajoy is resisting any “leftward” shift by his party and as a result has been doing even worse in the polls for the future national elections. After his current defeat in the “independencist” elections in Catalonia, Rajoy has dug in his heels even further. Question: Can Rajoy survive as leader of his party, or will he be replaced as was Tony Abbott in Australia by a slightly less rigid leader?

In Spain, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy of the conservative New Democracy Party is facing rising poll figures from Pablo Iglesias of Podemos, running on an anti-austerity platform similar to what was long promoted by Greece’s Syriza Party. New Democracy did quite badly in the May 24 local and regional elections. Rajoy is resisting any “leftward” shift by his party and as a result has been doing even worse in the polls for the future national elections. After his current defeat in the “independencist” elections in Catalonia, Rajoy has dug in his heels even further. Question: Can Rajoy survive as leader of his party, or will he be replaced as was Tony Abbott in Australia by a slightly less rigid leader?

Greece turns out to be the most interesting example of this shift. There have been three elections this year. The first was on January 25, when Syriza came into power, again to the surprise of many analysts, on an anti-austerity platform, using traditional left rhetoric.

When Syriza found European countries unwilling to budge on Greece’s demands to be relieved of many commitments concerning its debt, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras called for a referendum on whether or not to “reject” Europe’s terms. The so-called Oxi (No) vote on September 18 won hugely. We know what happened subsequently. The European creditors not only made no concessions but offered even worse terms to Greece, which Tsipras felt he had to accept in large part.

Once again, analysts concentrated on the “betrayal” by Tsipras of his pledge. The left caucus within Syriza seceded and formed a new party. In the melee, few commented on what happened in the New Democracy Party. There, its leader Antonis Samaras was replaced by Vangilis Meimaraki, a shift from 9-8 or maybe from 8-7, in an attempt to reap centrist votes away from Syriza.

The conservative shift leftward did not succeed. Syriza won again. The breakaway left group was wiped out in the elections. But why did Syriza win? It seems that the voters still felt they would do better, if only slightly better, with Syriza in minimizing the cuts to pensions and other “welfare state” protections. In short, in the worst possible situation for Greece’s left, Syriza at least did not lose ground.

What, you may wonder, does all this mean? It is clear that, in a world that is living amidst great economic uncertainty and worsening conditions for large segments of the world’s populations, parties in power tend to be blamed and lose electoral strength. So, after the rightward swing of the last decade or so, the pendulum is going the other way.

How much difference does this make? Once again, I insist it depends on whether you observe this in the short run or in the middle run. In the short run, it makes a lot of difference, since people live (and suffer) in the short run. Anything that “minimizes the pain” is a plus. Therefore, this kind of “leftward” swing is a plus. But in the middle run, it makes no difference at all. Indeed, it tends to obscure the real battle, the one concerning the direction of the transformation of the capitalist world-system into a new world-system (or systems). That battle is between those who want a new system that may be even worse than the present one and one that will be substantially better.