Source: Tom Dispatch

North American cicada nymphs live underground for 17 years before they emerge as adults. Many seeds stay dormant far longer than that before some disturbance makes them germinate. Some trees bear fruit long after the people who have planted them have died, and one Massachusetts pear tree, planted by a Puritan in 1630, is still bearing fruit far sweeter than most of what those fundamentalists brought to this continent. Sometimes cause and effect are centuries apart; sometimes Martin Luther King’s arc of the moral universe that bends toward justice is so long few see its curve; sometimes hope lies not in looking forward but backward to study the line of that arc.

Three years ago at this time, after a young Tunisian set himself on fire to protest injustice, the Arab Spring was on the cusp of erupting. An even younger man, a rapper who went by the name El Général, was on the verge of being arrested for “Rais Lebled” (a tweaked version of the phrase “head of state”), a song that would help launch the revolution in Tunisia.

Weeks before either the Tunisian or Egyptian revolutions erupted, no one imagined they were going to happen. No one foresaw them. No one was talking about the Arab world or northern Africa as places with a fierce appetite for justice and democracy. No one was saying much about unarmed popular power as a force in that corner of the world. No one knew that the seeds were germinating.

A small but striking aspect of the Arab Spring was the role of hip-hop in it. Though the U.S. government often exports repression — its billions in aid to the Egyptian military over the decades, for example — American culture can be something else altogether, and often has been.

Henry David Thoreau wrote books that not many people read when they were published. He famously said of his unsold copies, “I have now a library of nearly 900 volumes over 700 of which I wrote myself.” But a South African lawyer of Indian descent named Mohandas Gandhi read Thoreau on civil disobedience and found ideas that helped him fight discrimination in Africa and then liberate his own country from British rule. Martin Luther King studied Thoreau and Gandhi and put their ideas to work in the United States, while in 1952 the African National Congress and the young Nelson Mandela were collaborating with the South African Indian Congress on civil disobedience campaigns. You wish you could write Thoreau a letter about all this. He had no way of knowing that what he planted would still be bearing fruit 151 years after his death. But the past doesn’t need us. The past guides us; the future needs us.

An influential comic book on civil disobedience and Martin Luther King published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation in the U.S. in 1957 was translated into Arabic and distributed in Egypt in 2009, four decades after King’s death. What its impact was cannot be measured, but it seems to have had one in the Egyptian uprising which was a dizzying mix of social media, outside pressure, street fighting, and huge demonstrations.

The past explodes from time to time, and many events that once seemed to have achieved nothing turn out to do their work slowly. Much of what has been most beautifully transformative in recent years has also been branded a failure by people who want instant results guaranteed or your money back. The Arab Spring has just begun, and if some of the participant nations are going through their equivalent of the French Revolution, it’s worth remembering that France, despite the Terror and the Napoleonic era, never went back either to absolutist monarchy or the belief that such a condition could be legitimate. It was a mess, it was an improvement, it’s still not finished.

The same might be said of the South African upheaval Mandela catalyzed. It made things better; it has not made them good enough. It’s worth pointing out as well that what was liberated by the end of apartheid was not only the nonwhite population of one country, but a sense of power and possibility for so many globally who had participated in the boycotts and other campaigns to end apartheid in that miraculous era from 1989 to 1991 that also saw the collapse of the Soviet Union, successful revolutions across Eastern Europe, the student uprising in Beijing, and the beginning of the end of many authoritarian regimes in Latin America.

In the hopeful aftermath of that transformation, Mandela wrote, “The titanic effort that has brought liberation to South Africa and ensured the total liberation of Africa constitutes an act of redemption for the black people of the world. It is a gift of emancipation also to those who, because they were white, imposed on themselves the heavy burden of assuming the mantle of rulers of all humanity. It says to all who will listen and understand that, by ending the apartheid barbarity that was the offspring of European colonization, Africa has, once more, contributed to the advance of human civilization and further expanded the frontiers of liberty everywhere.”

Congo Square

The arc of justice is long. It travels through New Orleans, the city I’ve returned to again and again since Hurricane Katrina. It’s been my way of trying to understand not just disaster, but community, culture, and continuity, three things that city possesses as no place else in the nation. Hip-hop comes most directly from the South Bronx, but if you look at the 1970s founders of that genre of popular music, you see that some of the key figures were Caribbean, and if you look at their formative music, it included the ska and reggae that were infused with the influence of New Orleans. (In addition, that city’s native son and major jazz figure, Donald Harrison, Jr., was a mentor to seminal New York City rapper Notorious B.I.G.)

If you look at New Orleans, what you see is an astonishing example of the survival of culture — and of the culture of survival.

Maybe you’d have to do what I was doing in early 2011 — poke around in the origins of American music in New Orleans — to be struck by the way so many essential parts of it came from Africa in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and some of it returned to that continent again in recent years. I was looking at maps, making maps, thinking about how to chart the unexpected ways immaterial things move through time and space.

The saddest map I have ever seen is the oft-published one of the triangle trade, a vicious circle that isn’t even a circle. It depicts the routes of the eighteenth and nineteenth century European traders who brought manufactured goods from their continent to West Africa to exchange for human beings who were then transported to the United States and the Caribbean to be exchanged for raw materials, especially sugar, rum, and tobacco. It’s a map that tells of people made into tools and commodities, but it tells us nothing of what the enslaved brought with them.

Stripped bare of all possessions and rights, they carried memory, culture, and resistance in their heads. New Orleans let those things flourish as nowhere else in the United States during the long, obscene era of slavery, while the biggest slave uprising in U.S. history took place nearby in 1811 (its participants including two young Asante warriors who had arrived in New Orleans on slave ships five years earlier). From the mid-eighteenth century to the 1840s, the enslaved of New Orleans were permitted to gather on Sundays in the plaza on the edge of the old city known then and now as Congo Square.

“On sabbath evening,” the visitor H.C. Knight famously wrote in 1819, “the African slaves meet on the green, by the swamp, and rock the city with their Congo dances.” The great music historian Ned Sublette observes that this is the first use of rock as a verb about music, and in his marvelous book The World That Made New Orleans notes that what is arguably the first rock and roll record, Roy Brown’s 1947 “Good Rocking Tonight,” was recorded a block away.

In between, what Africans had brought with them continued its metamorphosis in the city: jazz famously arose from black culture near Congo Square, as did important rhythm and blues strains and influences, as well as performers, then funk, and eventually hip-hop. Funk arose in part from Afro-Cuban influences and from the African-American tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians — not Native Americans, but working-class African Americans. Their elaborate outfits and rites officially pay homage to the Native Americans who sheltered runaway slaves (and sometimes intermarried with them), but have a startling resemblance to African beaded costumes. The Mardi Gras Indians still parade on that day and other days, chanting and singing, challenging each other through song. One of the recurrent chants declares, “We won’t bow down.”

Though New Orleans is mainly famous for other things, it has also been a city of resistance — from the slave revolts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to late nineteenth century segregation-breaker Homer Plessy to Ruby Bridges, the six-year-old who in 1960 was the first Black child to integrate a white school in the South. The span of time is not as long as you might think: Fats Domino, one of the founding fathers of rock and roll, is still alive and has a home in the Lower Ninth Ward. The midwife at his birth a few blocks away was his grandmother, who had been born into slavery.

New Orleanian Herreast Harrison, a woman in her seventies, mother of jazzman Donald Harrison Jr., widow of a Mardi Gras Indian chief, cultural preserver, and a dynamic force in the city, said to me of Mardi Gras Indian culture:

“But those groups remembered their cultural heritage and practiced it there, that memory, they had this overarching memory of their pasts. And when they were there, they were free. And their spirits soared to the high heavens. They were themselves. In spite of limitations in every aspect of their lives. Where they should have felt like, ‘we are nothing,’ because you get brainwashed constantly about the fact that you’re a nobody… but they didn’t, they brought back. And now it’s part of the world, that music.”

And her son, Donald Harrison, Jr., added:

“One other very important thing that Congo Square represented in the culture was that no matter what’s going on in life you transcend the culture and Congo Square helps you. It transcends and puts you into a transcendental state so that you are free at that moment. Even today, that’s the power of the music and that’s why it brings us together. You have a moment of freedom where you transcend everything that’s going on around you. Berthold Auerbach said it so eloquently: ‘Music washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.’ At that moment you become free, which is why the music is part of the world now. Everybody wants a moment to transcend. It goes inside of you and you know where you can go to be free. No matter if you’re in Norway, South American, or Beijing, you know, ‘this music sets me free.’ So Congo Square set the world free, basically. It gives freedom to everyone around it.”

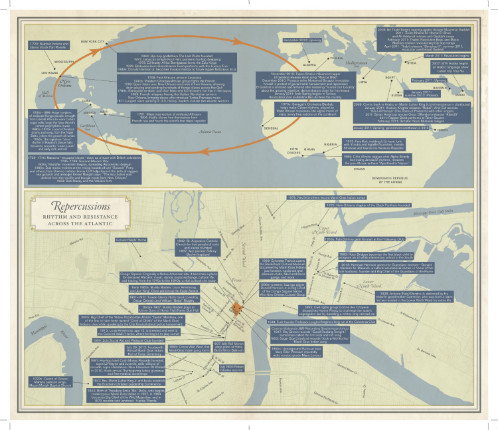

In my latest project, Unfathomable City: A New Orleans Atlas, I tried to convey what New Orleans music gave the world in a map labeled “Repercussions: Rhythm and Resistance Across the Atlantic.” Those involuntary émigrés brought by slave ship were said to have nothing, but what they had still reaches and spreads and liberates.

Click here to see a larger version

Repercussions: Rhythm and Resistance Across the Atlantic. Map concept and research: Rebecca Solnit. Cartography: Shizue Seigel. Design: Lia Tjandra. c Univ. of CA Press, 2013.What we call the Arab Spring was first of all the North African Spring — in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya — and hip-hop was already there. It has, in fact, become a global means of dissent, from indigenous Oaxaca, Mexico, to Cairo, Egypt. Which does not mean that everything is fine (or that hip-hop can’t also be used for consumerism or misogyny). It’s a reminder, however, that even in the most horrific of circumstances, something remarkable more than survived; it throve and grew and eventually reached around the Earth.

Repercussions: Rhythm and Resistance Across the Atlantic. Map concept and research: Rebecca Solnit. Cartography: Shizue Seigel. Design: Lia Tjandra. c Univ. of CA Press, 2013.What we call the Arab Spring was first of all the North African Spring — in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya — and hip-hop was already there. It has, in fact, become a global means of dissent, from indigenous Oaxaca, Mexico, to Cairo, Egypt. Which does not mean that everything is fine (or that hip-hop can’t also be used for consumerism or misogyny). It’s a reminder, however, that even in the most horrific of circumstances, something remarkable more than survived; it throve and grew and eventually reached around the Earth.

Nearly three years after the first sparks of the Arab Spring began, it’s wiser to consider it, too, barely begun rather than ended in failure. More than two years after the first members of Occupy Wall Street began decamping in Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan, that movement is not over either, though almost all the encampments have subsided and the engagement has new names: Occupy Sandy, Strike Debt, and more. That everything continues to metamorphose seems a better way to think of social upheavals than obituaries and epitaphs.

Maps of the Unpredictable

Whenever I look around me, I wonder what old things are about to bear fruit, what seemingly solid institutions might soon rupture, and what seeds we might now be planting whose harvest will come at some unpredictable moment in the future. The most magnificent person I met in 2013 quoted a line from Michel Foucault to me: “People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does.” Someone saves a life or educates a person or tells her a story that upends everything she assumed. The transformation may be subtle or crucial or world changing, next year or in 100 years, or maybe in a millennium. You can’t always trace it but everything, everyone has a genealogy.

In her forthcoming book The Rise: Creativity, the Gift of Failure, and the Search for Mastery, Sarah Lewis tells how a white teenager in Austin, Texas, named Charles Black heard a black trumpet player in the 1930s who changed his thinking — and so our lives. He was riveted and transformed by the beauty of New Orleans jazzman Louis Armstrong’s music, so much so that he began to reconsider the segregated world he had grown up in. “It is impossible to overstate the significance of a 16-year-old Southern boy’s seeing genius, for the first time, in a black,” he recalled decades later. As a lawyer dedicated to racial equality and civil rights, he would in 1954 help overturn segregation nationwide, aiding the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case ending segregation (and overturning Plessy v. Ferguson, the failed anti-segregation lawsuit launched in New Orleans 60 years earlier).

How do you explain what Louis Armstrong’s music does? Can you draw a map of the United States in which the sound of a trumpeter in 1930s Texas reaches back to moments of liberation created by slaves in Congo Square and forward to the Supreme Court of 1954?

Or how do you chart the way in which the capture of three young American hikers by Iranian border guards on the Iraq-Iran border in 2009 and their imprisonment — the men for 781 days — became the occasion for secret talks between the U.S. and Iran that led to the interim nuclear agreement signed last month? Can you draw a map of the world in which three idealistic young people out on a walk become prisoners and then catalysts?

Looking back, one of those three prisoners, Shane Bauer, wrote, “One of my fears in prison was that our detention was only going to fuel hostility between Iran and the U.S. It feels good to know that those two miserable years led to something, that could lead to something better than what was before.”

Bauer later added:

“The reason our tragedy led to an opening between the United States and Iran was that many people were actively working to end our suffering. To do so, our friends and families had to strive to build a bridge between the U.S. and Iran when the two governments were refusing to do it themselves. Sarah [Shourd, the third prisoner] is not a politician and she has no desire to be, but when she was released a year before Josh and me, she made herself into a skilled and unrelenting diplomat, strengthening connections between Oman and the U.S. that ultimately led to these talks.”

A decade ago I began writing about hope, an orientation that has nothing to do with optimism. Optimism says that everything will be fine no matter what, just as pessimism says that it will be dismal no matter what. Hope is a sense of the grand mystery of it all, the knowledge that we don’t know how it will turn out, that anything is possible. It means recognizing that the sound of a trumpet at a school dance in Austin, Texas, may resound in the Supreme Court 20 years later; that an unfortunate hike in the borderlands might help turn two countries away from war; that Edward Snowden, a young NSA contractor and the biggest surprise of this year, might revolt against that agency’s sinister invasions of privacy and be surprised himself by the vehemence of the global reaction to his leaked data; that culture which left Africa more than 200 years ago might return to that continent as a tool for liberation — that we don’t know what we do does.

That Massachusetts pear tree is still bearing fruit almost 400 years after it was planted. The planter of that tree also helped instigate the war against the Pequots, who were massacred in 1637. “The survivors were sold into slavery or given over to neighboring tribes. The colonists even barred the use of the Pequot name, ‘in order to cut off the remembrance of them from the earth,’ as the leader of the raiding party later wrote,” according to the New York Times.

For centuries thereafter, that Native American nation was described as extinct, erased, gone. It was written about in the past tense when mentioned at all. In the 1970s, however, the Pequots achieved federal recognition, entitling them to the rights that Native American tribes have as “subject sovereign nations”; in the 1980s, they opened a bingo hall on their reservation in Connecticut; in the 1990s, it became the biggest casino in the western world. (Just for the record, I’m not a fan of the gambling industry, but I am of unpredictable narratives.)

With the enormous income from that project, the tribe funded a Native American history museum that opened in 1998, also the biggest of its kind. The new empire of the Pequots has been on rocky ground since the financial meltdown of 2008, but the fact that it arose at all is astonishing more than 150 years after Herman Melville stuck a ship called the Pequod in the middle of his novel Moby Dick and mentioned that it was named after a people “now extinct as the ancient Medes.” Are there are longer odds in New England than that a people long pronounced gone would end up profiting from the bad-math optimism of their neighbors?

Meanwhile, that pear tree continues to bear fruit; meanwhile, hip-hop continues to be a vehicle for political dissent from the Inuit far north to Latin America; meanwhile, diplomatic relations with Iran have had some surprising twists and turns, most recently away from war.

I see the fabric of my country’s rights and justices fraying and I see climate change advancing. There are terrible things about this moment and it’s clear that the consequences of climate change will get worse (though how much worse still depends on us). I also see that we never actually know how things will play out in the end, that the most unlikely events often occur, that we are a very innovative and resilient species, and that far more of us are idealists than is good for business and the status quo to acknowledge.

What I learned first in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina was how calm, how resourceful, and how generous people could be in the worst times: the “Cajun Navy” that came in to rescue people by boat, the stranded themselves who formed communities of mutual aid, the hundreds of thousands of volunteers, from middle-aged Mennonites to young anarchists, who arrived afterward to help salvage a city that could have been left for dead.

I don’t know what’s coming. I do know that, whatever it is, some of it will be terrible, but some of it will be miraculous, that term we reserve for the utterly unanticipated, the seeds we didn’t know the soil held. And I know that we don’t know what we do does. As Shane Bauer points out, the doing is the crucial thing.

Rebecca Solnit is an activist, TomDispatch.com regular, and author of many books, the latest of which, The Faraway Nearby, was published in June, 2013. Her first essay for TomDispatch.com turned into the book Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, since translated into eight languages. Other previous books include: A Paradise Built in Hell, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, The Battle of The Story of the Battle in Seattle (with her brother David), and Storming The Gates of Paradise: Landscapes for Politics. She is a contributing editor to Harper’s Magazine.