Instead, they say, the foreign investment and extractive economy has not brought the promised work and riches, but poverty and pollution. The massive infrastructure projects may have brought development – but for the cities and industrial heartlands, not those living in the rural territories where the true price of such constructions is paid.

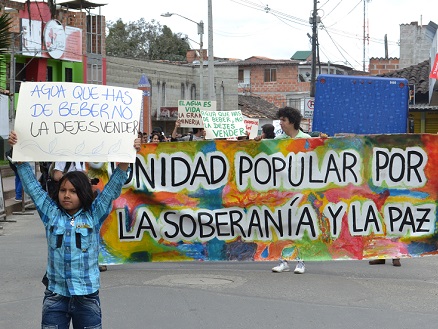

In one of Colombia’s key strategic and resource rich areas, Eastern Antioquia, a nascent social movement is unifying disparate social issues under one banner – the defense of water. In October, this new movement announced its arrival when organizations from across the region descended on the town of El Carmen de Viboral to stage a “Water Festival.”

Present at the festival were activists, community leaders and supporters from every corner of Eastern Antioquia – 23 municipalities in the northwest of Colombia characterized by its natural beauty, richness in resources and recent history of bloody violence when paramilitaries fought to drive leftist guerrillas from the region. On the agenda were issues pertinent to the whole country – mining, infrastructure mega-projects and the threat to the way of life of traditional campesino (small scale farmers and rural workers) communities.

“The East [of Antioquia] is a zone where there are a lot of forests and a lot of water, and now that private and multinational companies have begun to enter the region, the campesino communities are very worried,” said Alba Gomez, the El Carmen Coordinator for Colombian NGO Conciudadania and one of the event organizers. “We feel the war is going to repeat itself because it was like this last time – they begin by making incursions to displace the campesinos.”

Leading the charge of this new invasion have been the mining companies. Over the last decade, Colombia has witnessed an explosion in mining, with the amount of land concessioned to companies rising from 1.13 million hectares to 8.53 million hectares during the previous government of President Alvaro Uribe (2002-2010), a policy that has continued during the current administration of President Juan Manuel Santos.

Although the department of Antioquia has long been one of Colombia’s mining hubs, until the recent boom, Eastern Antioquia remained relatively untouched, with just a small informal mining sector boosting an economy based on agriculture, cattle ranching and local industries. Now, mining concessions have been granted or are awaiting approval in nearly every municipality.

The advance of this large scale mining has gravely threatened Eastern Antioquia’s eco-systems with practices that contaminate soils and water and use up much of the region’s water supplies.

“The policies in East Antioquia are going to leave us without water, without wildlife and without riches, all that will be left is a desert,” said Uber Sanchez, a small scale miner from the municipality of San Rafael. “The only thing the multinationals bring to this country is deterioration, pollution and poverty.”

Miners such as Sanchez believe the arrival of the big mining companies is also the death knell for the small scale mining that has been practiced in the region for generations.

While the government has promoted the advance of large scale mining, labeling it one of the country’s “engines of development,” it has simultaneously cracked down on the informal and illegal mining sector, which it blames for much of the mining related contamination. And not without reason – unlike large scale mining, informal miners use mercury in processing ore, which in areas where such mining is rife has created an ecological disaster.

However, while local miners participating in the Water Festival acknowledge the environmental damage these techniques cause, they insist they are being made scapegoats by the government and that the only path towards a sustainable mining sector lies with them, and not the multinationals currently dividing up the region and the country’s spoils.

“Nowadays there are techniques for clean production that are profitable and economical,” Sanchez said. “The only thing we need is the political, economical and technical support of the government and we could practically become our own multinational working for the benefit of the country.”

While the threat from mining comes from diversion and contamination of water resources, the region’s water eco-system faces a much more direct challenge – hydroelectric power. Currently, the hydroelectric dams of Eastern Antioquia generate around 35 percent of Colombia’s electricity, with six reservoirs and five hydroelectric centers currently running. This is set to expand rapidly, with several new dams slated for construction and more under consideration.

However, while the residents have borne the brunt of the impact of these projects – displacement, loss of land, and damage to the eco-system – they have not seen the benefits.

“What the people here have experienced is people from outside coming to take their water,” said Benjamin Cardona, Conciudadania’s territorial director for Eastern Antioquia, who has spent decades working with the region’s communities. “[Colombian state infrastructure companies] EPM, Isagen, ISA, have lived off the east’s water but while they are providing water and energy to Medellin, public services here cost 300 times more than in the city.”

Fears are now growing that this situation could get even worse with government plans to sell off its 57% stake in the company responsible for many of these projects – Isagen. At present, Isagen policies require any investment to be accompanied by public consultations, environmental management and social investments that go beyond what is required by law.

According to Isagen unionists, privatization of the company would not only lead to further increases in utility prices, it would also see these investments drastically scaled back as social commitments give way to maximizing profits.

“When they sell off Isagen, all of this social investment will be lost,” said Helber Castaño, Secretary of the company union Sintraisagen.

The invasion of mining and infrastructure projects has not only endangered the region’s eco-systems and water reserves, it is also threatening a community already under siege – the campesinos.

Traditionally, the region’s small scale farmers have lived by growing crops such as corn, plantain and beans for the local market, and coffee and sugar for exports. However, the campesinos are now being assaulted on all sides; faced with increased competition from abroad thanks to recently signed Free Trade Agreements, crashing sugar prices, a coffee sector in crisis, and the advance of large scale agriculture. Now, with the loss of lands and pollution brought by the advance of mega-projects, they feel they are facing an existential threat, not only to their livelihoods, but also to their way of life.

“The companies are placing a strain on these territories, which are rich with water,” said Oscar Ure, a local campaigner for food sovereignty and bio-diversity. “They are threatening all these traditions and cultures because the state and the multinationals want to launch these projects that have nothing to do with the people here.”

While the rallying cry to assemble the organizations in El Carmen was water, for those that saw a generation of community leaders lost to the dirty war violence of right-wing paramilitary death squads, it also marks a step towards leaving behind the fear that kept the region’s people cowed and silent for so long.

“After the armed conflict struck Eastern Antioquia we couldn’t rise up,” said Gomez. “The social fabric was broken, there was distrust and fear.”

With the paramilitaries demobilized – although successor groups still terrorize parts of the country – and the guerrillas driven back by a military offensive and now participating in peace talks, a semblance of normality has returned to the region. And Gomez is optimistic the communities can leave the fear behind and speak out against the new invasion.

Key to this is the involvement of the local youth, she says. Various youth networks are active participants in the movement, a fact that fills the older heads with optimism.

“I feel hope there, because they don’t carry the same baggage, they have learned about the history of their parents and their grandparents and now they have a different way of thinking,” said Gomez. “They also have a long road to walk.”

***

James Bargent is a freelance journalist based in Medellin, Colombia. He has reported on Colombia and Latin America for various publications including the Independent, the Miami Herald, the Toronto Star, In These Times, the Times Education Supplement, AlterNet, Toward Freedom and Green Left Weekly.