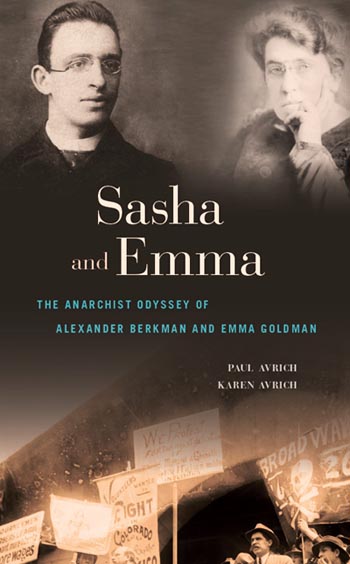

Reviewed: Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, by Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012, 401 pages, hardcover, $35.

Reviewed: Sasha and Emma: The Anarchist Odyssey of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, by Paul Avrich and Karen Avrich, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012, 401 pages, hardcover, $35.

Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman were arrogant, self-righteous kids who thought that their heroics could unlock the revolution and change the world. In other words: typical anarchists. And as typical anarchists, they were thoughtful, generous, creative idealists, whose devotion to their cause was only rivaled by their devotion to their friends.

It was after a commemoration of the Haymarket affair that the two became lovers. Looking back, Goldman wrote that she had found herself attracted to his “earnestness. . . his self-confidence, his youth — everything about him drew me with irresistible force.” Soon, an “overpowering yearning possessed me. . . an unutterable desire to give myself to Sasha.” And it was not long before “Deep love for him welled up in my heart. . . a feeling of certainty that our lives were linked for all time.”

They were lovers only briefly, but their friendship endured and their lives became permanently intertwined. Together they worked toward the ideal of a free and equal society — organizing meetings, battling censorship, editing newsletters, writing, speaking, and in one case conspiring to assassinate a strike-breaking industrialist. (The attempt failed, leading Berkman to prison.) They were deported together, to Soviet Russia, and they escaped Russia together as well.

Historian Paul Avrich’s last work, completed after his death by his daughter, Karen Avrich, tells the story of these two remarkable lives — their romance, their friendship, their struggle for freedom, and their exile.

Unfortunately the book offers not the single story of a relationship, but something like two biographies that cannot be disentangled. Its narrative, like most lives, is really a collection of curious digressions: debates about propaganda by the deed, free speech fights and legal battles, a meeting with Lenin, the anarchist influence on Eugene O’Neil. All those points are interesting in their own right, but they are also incidental, if not actually irrelevant, to the main subject of the book. Little of the passion, the warmth, or the tenderness shows through the blur of activity and the flash of historical events.

Yet for the two anarchists, it was precisely their friendship that lay at the center of it all. As Goldman wrote in one letter:

It is fitting that I should tell you the secret of my life. . . . It is that the one treasure I have rescued from my long and bitter struggle is my friendship for you. . . . I know of no other value whether in people or achievements than your presence in my life and the love and affection you have roused.

True, I loved other men. But it is not an exaggeration when I say that no one ever was so rooted in my being, so ingrained in every fiber as you have been and are to this day. Men have come and gone in my long life. But you my dearest will remain for ever. I do not know why this should be so. Our common struggle and all it has brought us in travail and disappointments hardly explains what I feel for you. Indeed, I know that the only loss that would matter would be to lose you, or our friendship.

And Berkman wrote, on a separate occasion:

My dear, dear Sailor, . . . Our friendship and comradeship of a lifetime has been to me the most beautiful inspiring factor in my whole life. And after all, it is given to but few mortals to live as you and I have lived. Notwithstanding all our hardships and sorrows, all persecution and imprisonment — perhaps because of it all — we have lived the lives of our choice. What more can one expect of life! . . . You have been my mate and my comrade in arms — my life’s mate in the biggest sense, and your wonderful spirit and devotion have always been an inspiration to me, as I’m sure your life will prove an inspiration to others long after both you and I have gone to everlasting rest.

The book’s grandest moments are always in quotation, and of such moments there are far too few. One gets the sense that the story of this relationship — a friendship so uniquely their own — would be better told with a collection of letters, each offering a glimpse inside that secret world two people build when they love one another for a very long time. Instead, the bulk of the book is concerned with the outer events of their lives — the attentats, the lecture tours, the arrests, imprisonment, deportations, the controversies within anarchism. That background — the history of the anarchist movement — overshadows the drama of these two individual lives. We get but a small taste of at the personalities involved, what they were like, what connected them, how their relationship shaped and was shaped by their ideals.

What does come across, usually quietly, is the depth of the connection that came with time. “The greatest of joys,” Goldman wrote to Berkman, “is the fact that you have remained in my life, and that our friendship is as fresh and intense as it was many years ago, more mellow and understanding than when we were both young and unreasonable.”

For nearly half a century, from the 1890s to the 1930s, Goldman and Berkman practically personified — to the broad US public, at least — what it was to be an anarchist. During that time they matured, the anarchist movement changed, and yet the image retained something of the fire and the recklessness of their youth. Sasha and Emma helps us not only to look beyond the mythologizing, but to show how the various moments, conflicting impulses, and incongruent views can fit together to form a life, a romance, a movement, or a philosophy.

Kristian Williams is the author of Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America and, most recently, Hurt: Notes on Torture in a Modern Democracy. He is presently at work on a book about Oscar Wilde and anarchism.