“I came here to find a better life,” he said at Place de Bastille, in central Paris, where he and hundreds others had camped out for nearly a month. “And I still haven’t found it.”

Since October 2009, thousands of sans papiers, or undocumented workers, have been striking in France. Hailing mainly from former West African French colonies, but also from China and North Africa, the sans papiers decided to come out of the shadows to demand regularization.

“Staying hidden wasn’t a choice,” explained Ibrahima, an organizer for the sans papiers. “The police would harass us all the time. They stopped us everywhere.”

The initial strike culminated eight months later in a tent-city protest beside the busy Bastille, a plaza where the French revolution erupted.

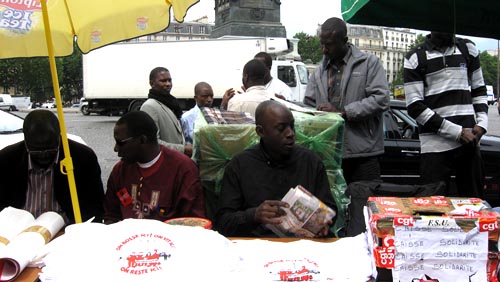

“We work here, we pay taxes here and we declare our earnings,” said Ibrahima, while holding court at a table inside the tent-city. “We’ve lived here for years and have families. And yet we can be thrown out at any minute.”

Before the strike, most of the sans papiers worked low paying jobs in construction, security, cleaning, and the service industry. Now they spend their days raising awareness and funds for their cause. At the tent-city the strikers stand at the busy intersections, collecting donations and passing out flyers about their plight. Drum circles often form and the largely Muslim population meets under tarpaulin tents for their daily prayers.

If they are lucky, they survive off the support of family and friends. But for the majority, if it were not for the daily donations of food and money from charities and human rights groups, the situation would be worse.

“The most difficult part is just living on the streets of the Bastille,” said Mr. Ibrahima. “After eight months, we have run out of money. I’m lucky because my family supports me while I’m striking, but for most, they are on their own. Some have already lost their housing. It’s hard, but it’s worth it.”

That was back in early June. Now, after meetings between the sans papiers, the largest union in France, Confédération générale du travail (CGT – the General Confederation of Labor), and the ministry of immigration, the government has agreed to certain ‘adjustments’ to harmonize the status of undocumented workers.

“Assessments allowed us to determine the difficulties surrounding the application [for legal work permits] and to determine the necessary adjustments,” declared the Ministry of Immigration in a statement last June.

“Assessments allowed us to determine the difficulties surrounding the application [for legal work permits] and to determine the necessary adjustments,” declared the Ministry of Immigration in a statement last June.

The French daily Le Figaro reported on June 19th, 2010 that, “each clandestine worker received a temporary three month authorization to send in their applications,” for normalization.

The sans papiers movement began back in 2008 around the Paris metropolitan area when undocumented fast food workers sporadically started striking and occupying their places of work. The CGT soon took up the cause of the sans papiers, lobbying on their behalf and acting as an umbrella organization. It now is not uncommon to see many of the sans papiers protesting alongside other CGT members at general strikes. Currently a wide array of unions support the sans papiers.

The movement later gained steam in 2009 after a gaffe by then Immigration Minister Brice Hortefeux. According to the news site France 24, he was caught on camera saying to a colleague of Arabic descent, “one of you is ok but when there are many, there’s a problem.” The remark sparked the 24 Hours Without Us, a call by immigration activists for a nationwide boycott of work and purchasing for a 24 hour period. The idea being that a day without immigrants would demonstrate the importance of new comers to the French economy and society.

Under the Sarkozy administration immigration has emerged as a flashpoint. The government has sponsored controversial debates on national identity and recently pushed to ban the wearing of the Islamic burqa and niqab in public. Thousands of undocumented immigrants have been deported.

Since the agreement with the Sarkozy government, Diallo Ibrahima and the rest of the sans papiers camping out beneath Place de Bastille have returned home.

“We’ve never doubted for one day that we won’t win,” said Ibrahima when we spoke, before the government’s decision. “I know it sounds crazy, but that is what keeps driving us forward.

Sammy Loren is a documentary filmmaker and freelance journalist currently based in Los Angeles, California. To check out his other projects visit, nuevaorleansmovie.wordpress.com