We’re re-posting this article on unrest in Haiti from a couple weeks ago so readers can get caught up on the background of ongoing protests in the island nation. Last week, it was reported that 17 people had been killed and 187 injured during protests, many by police. Demonstrations against President Jovenel Moïse continued through Friday.

Gasoline is fueling unrest in Haiti for the second time this year.

The Caribbean country, which relies heavily on oil imported from Venezuela, has suffered fuel shortages and blackouts since Venezuela’s crisis-stricken government stopped oil shipments earlier this year.

Throughout September, an acute fuel shortage has triggered street protests in the capital of Port-au-Prince, forcing schools and shops to close. Hospitals are barely functioning.

The crisis is beginning to ease in Port-au-Prince as more oil arrives. But the rest of the country remains paralyzed.

In Haiti’s Cap Haitian region and rural northeast, the humanitarian situation is dire. For over a year, a severe drought has left people with hardly any access to water. Crops have shriveled and the Dominican Republic just closed its border with Haiti, so food that once came from there is in short supply.

A failing economic model

Haiti’s fuel shortages are one manifestation of the political crisis that has destabilized the country since the violent 1991 coup d’etat that replaced President Jean-Bertrand Aristide with a repressive military regime.

That three-year dictatorship left Haiti’s democracy fragile. Haiti has had 11 prime ministers since 2010. The deeply dysfunctional government of President Jovenel Moïse has not yet passed a 2019 budget.

This prevents the government from receiving the international loans that it relies on to fund over 20% of its operating budget. As a result, the government owes US$130 million in arrears to its fuel suppliers.

Haiti’s financial struggles are also, in large part, the result of an ill-conceived economic system that has failed to meet Haiti’s needs for over a century.

Ever since the American military occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934, its economic and social policies have been designed to attract foreign investment. The plan, which was crafted in the 1910s and 1920s by the U.S. military government, was to “develop” this rural Caribbean country by making it an appealing operating environment for U.S. firms.

In practice, that meant keeping Haitian wages, corporate taxes and tariffs low. In exchange, the theory went, foreign investment would bring infrastructure development and jobs, benefiting all Haitians.

American agro-corporations began profitably cultivating cash crops like coffee, bananas and sugar in Haiti in the early 20th century.

In 1926, American businessmen backed by the American military government seized more than 12,000 acres of fertile land from Haitian peasants in the Cap Haitian region to grow sisal, a fibrous plant used in weaving. To make room for this massive industrial operation, thousands of families were evicted from their land.

The intensive cultivation of just one crop over two decades so depleted the soil that food production across Cap Haitian was threatened.

This process of exploitation followed by scarcity and environmental degradation has repeated itself for decades.

Chasing low-wage labor and free trade, U.S. corporations and military agencies have established sugar cane plantations, rubber plantations and textile factories in Haiti for the past 100 years, with similarly disappointing results for workers and the environment.

Empty industrial parks

I am a cultural anthropologist who studies industrialization and informal economies in Haiti. Over the past seven years, I’ve spoken with dozens of Haitian factory workers, small farmers and entrepreneurs about their experiences with this kind of foreign-funded development project.

After decades of extremely business-friendly policies, three quarters of Haitians still live on less than $2.40 a day. The United States, Haiti’s main trade partner, has continued to enjoy the favorable trade policies it created in the early 1900s, which allow U.S. companies to sell government-subsidized American rice and sugar to Haitians at prices that have left Haitian farmers unable to compete.

One modern development project is painfully emblematic of Haiti’s failed economic model.

The Caracol Industrial Park, which opened in northeast Haiti in 2012, was supposed to be the centerpiece of the reconstruction effort in Haiti after its devastating 2010 earthquake. Developed by the Clinton Foundation, U.S. State Department and the Inter-American Development Bank, Caracol was supposed to create 60,000 jobs in the garment and assembly industries on farmland that, at the time, fed 4,000 people.

According to then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the industrial park would “put Haiti finally on the path to broad-based economic growth.”

The development took advantage of new, post-earthquake U.S. policies offering duty free Haitian garment exports and giving tax breaks to corporations that moved into this new Haitian free-trade zone.

Today, fewer than 15,000 people work in the factories at Caracol – a quarter of promised jobs. Most work long hours in bad conditions for less than US$5 a day.

The Haitian peasant farmers evicted by the Haitian state from their land so the park could be built did not get jobs at Caracol, nor were government promises to resettle them met. Today, many of them live in poverty on the outskirts of the park.

A bridge to nowhere

Failed factories and exploitative agricultural ventures are not solely responsible for Haitians’ poverty – or for their anger.

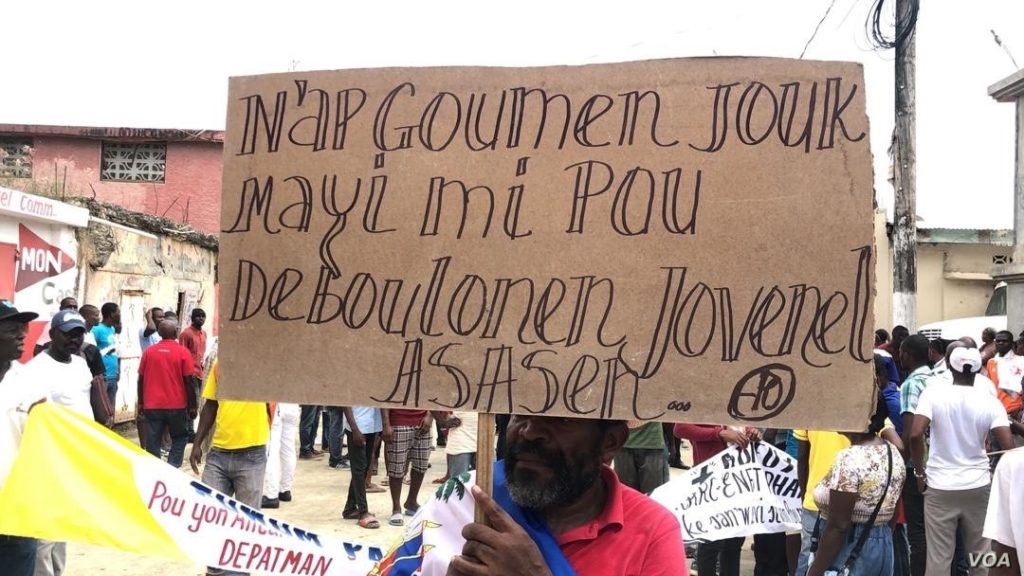

In June 2019, protesters took to the streets to demand the resignation of President Moise of the Tet Kale Party, who is accused of embezzling funds through fake construction companies.

Moise and his Tet Kale predecessor, President Michel Martelly, are accused by his own government of siphoning billions of dollars in development aid from Petrocaribe, a Venezuelan fund that provided low-interest loans to help rebuild Haiti in exchange for oil purchases.

The scheme was revealed in a stunning, 604-page report submitted in May 2019 to the Haitian Senate by the Superior Court of Auditors and Administrative Disputes.

The report explained why construction that began on hundreds of roads, bridges, hospitals, wharves, schools and soccer stadiums after Haiti’s 2010 earthquake was never finished. In southern Port-au-Prince, a gigantic half-built hospital and a bridge to nowhere serve as daily reminders of government embezzlement.

Haiti’s bright side

Fuel shortages and unscrupulous politicians may be a daily reality in Haiti, but there are positive things happening there, too.

In 2012, the 42-acre Martissant Park opened in southern Port-au-Prince. It features a large library, dense forests and environmental and educational programming.

To restore this urban forest and make it useful to locals, the Haitian foundation Fokal worked with city and state officials to remove and compensate squatters, upgrade surrounding neighborhoods and institute municipal trash pickup – a rare example of good governance.

And, in January, a coalition of peasant farmers evicted to make way for the Caracol Industrial Park won a historic settlement against the International Development Bank. With legal help from the Accountability Counsel, an American nonprofit, 4,000 people will receive reparations in the form of small plots of land, employment and training opportunities.

As frequent protests in Haiti show, people are well aware of the systemic problems hurting their economic and political systems. On the street, in their neighborhoods and abroad, they are demanding better.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Author bio:

Vincent Joos is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Florida State University