Note: On Monday, December 12th in Burlington, Vermont, Toward Freedom is hosting An Evening with Investigative Journalist Greg Palast – Why We Occupy: How Wall Street Picks the Bones of America

This article was originally published in Vermont Digger

In his new book, Vultures’ Picnic, Palast has pulled together documents and stories from more than three decades of detective work, unraveling the schemes of what he labels the “Energy-finance Combine” and exposing several real life “vulture” capitalists.

On Dec. 12, he will visit Burlington and share some of his findings at Main Street Landing during a 7 p.m. talk titled “Why We Occupy: How Wall Street Picks the Bones of America,” which is sponsored by Toward Freedom.

Palast is after very big game, powerful figures like Gulf Coast billionaire R. King Milling, banker and former chair of both British Petroleum and Goldman Sachs International Peter Sutherland, Michael Sheehan (a.k.a. Goldfinger), who made millions on Zambia’s debt, and “uber-vulture” Paul Singer, another billionaire who is currently helping Mitt Romney run for president.

Why are they called vultures? The name was actually bestowed – “with admiration” – by their banks, Palast notes. “They are international repo men who seize control of the finances of some of the poorest nations on the planet. They get old debts and collect hundreds of times of what they have spent,” he explains.

“The No. 1 U.S. vulture is Paul Singer, an economic advisor to Mitt Romney,” he noted in an interview with VTDigger.org.

In Vultures’ Picnic, Palast reveals that Singer, also a top donor to the Republican Party, “picked up bonds with a face value printed on them of $100 million” during the Congo’s civil wars. He paid about $10 million, but won a judgment to collect $400 million.”

Earlier, Singer also made a killing on Owens Corning, buying the company cheap after revelations that its asbestos plants were linked to worker deaths.

“Simply by cutting the amount paid to the victims, he could boost the company’s value,” Palast explains. Over time legal and public attacks on the workers “chiseled away the compensation expected to be paid by the asbestos companies, boosting the firms’ net worth. Singer then flipped Corning, selling it for a neat billion-dollar profit.”

But what drove Singer to go after Palast, he thinks, was his report “from the Congos (there are two nations in Africa called ‘Congo’) where there’s a cholera epidemic due to lack of clean water. Singer paid we’re told about $10 million for some ‘debt’ supposedly incurred by the Republic of Congo. Congo would pay the $10 million, but Singer had begun seizing about $400 million in the poor nation’s assets.”

A recent call to the BBC in London from Singer’s office conveyed a simple but chilling message: We have a file on Greg Palast.

“They really want to smear me and implied that a lawsuit was coming,” he says. “So, these are not minor players. Singer makes his money by literally killing babies, according to the former Deputy Secretary of the UN. And what Singer wants is Palast off the air.”

What’s in that threatening file? Palast tells the story himself in the book. As he put it recently, “I was caught going ‘undercover’ on an investigation with a comely young politician to get information. (Got the story …and my photo on the front page of the Mirror.) There. Read it all and see the photos in Chapter 9. Now you have it. Now I’ve taken away their favorite bullet: character assassination.”

Covering scenes of corporate crime

Vultures’ Picnic isn’t just a book, although it is an entertaining, sometimes startling read. It is also a long-term, multi-media project that includes a video companion, an enhanced online version with electronic files, a comic book series, and investigative TV reports for BBC and Democracy Now!

Palast suggests downloading Chapter One free from his website for a taste.

As the subtitle suggests, it is a story of pursuit, in this case a hunt for “petroleum pigs, power pirates, and high-finance carnivores.” Palast calls his approach to the material “reportage verité.” Others describe it as “pulp non-fiction,” almost a new genre.

When asked why he opted for a style that reads like a real-life detective story, gradually revealing clues rather than laying out conclusions up front, he replies, “People know about me from reporting on the presidential voting scandal. There I gave you the information that I cover. I thought it was important to say how I’m getting it – and sometimes failing to get it.”

In the past Palast has looked into the grounding of the Exxon Valdez, investigated Enron and worked with advocacy groups fighting corporate misdeeds. In 1988, he headed a civil racketeering probe into the Long Island Light Company. It looked like a great victory with a jury award of $4.8 billion, but a federal judge reversed the verdict. In 2000 Palast assembled evidence that Gov. Jeb Bush and his allies in Florida had rigged ballots to deliver the state for George W Bush. Four years later, he charged that vote “spoilage” had changed another presidential election outcome.

This story begins in the midst of a tense New York stakeout, then moves rapidly from Azerbaijan to Africa and the Arctic as he searches for the truth about BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster. What he discovers is a cover up: an identical blow-out, just like the one in the Gulf of Mexico, two years earlier in the Caspian Sea.

“The information we got from an eyewitness right after the blow out was that this was not the first time,” he says. “And it was the same reason, cheap crap cement. And they covered it up by beatings and bribery and blow jobs. Vulture Picnic is saying that they covered this up – and by doing that eleven guys died. I’m saying, as a former racketeering and fraud investigator, that it was a crime.”

Forget official claims of shock, he says. “All the oil companies knew about the problem prior to the blow out, and the Department of State may have hidden it from Congress.”

There has so far been no admission of prior knowledge, and, in any case, few questions have been asked by the U.S. press. Unlike journalists operating in the United States, however, Palast, an American who grew up in Los Angeles, is required under British law to present his evidence as a journalist to those he accuses.

“And they have never denied it,” he said. “Did you have another blow out? No denial, just blah blah blah.” Over the years, he adds, the British government has become an arm of BP’s imperial power.

And what is BP an arm of? “Actually, BP is an arm of Morgan Stanley,” he replies. “It used to be that BP was an extension of military intelligence, now the roles are reversed.”

He says he has identified at least three crimes committed in this case. No. 1 is that “BP destroyed the Caspian Sea and the Gulf. The Gulf of Mexico is a crime scene. Crime number two: The government knew and covered it up. And crime number three,” he continues, “The U.S. press is ignoring it, except maybe a public whipping, maybe.”

Palast has limited respect for most mainstream media. “The New York Times is a local paper that does gossip,” he says, “and NPR has become the National Petroleum Network. In Britain I’m mainstream, I work for the BBC and the Guardian. So, they can’t tell us that they didn’t know this.”

When he brings an exposé across the Atlantic such outlets rarely cover the story and tend to treat him like an “alternative” journalist. Although he enjoys working with Amy Goodman and Pacifica Radio, the situation can be frustrating. Even when there is coverage, it often misses the bigger point.

“I hate the bad apple model,” he explains, referring to the media’s preference for finding individual culprits over taking on institutional problems “That’s why I hated the Enron story,” he recalls. “I wrote about it as an example. The whole tree is rotten to the roots; that is the key. And the so-called investigative journalists are the biggest part of the cover up because they find a bad guy for you to pick on. This justifies the status quo.”

Cement, steel and fraud

Since Palast is visiting Vermont, the conversation turned to nuclear power and the expectation that Vermont Yankee may close next March. “The operative word is ‘may,’ he notes before pivoting to diesel generators, Japan’s Fukushima plant disaster, and his investigation of the Shoreham nuclear plant more than 25 years ago.

In a chapter called Fukushima, Texas, Vultures’ Picnic tackles how nuclear plant owners — from Tokyo Electric to Entergy – pinch pennies and play games with emergency standards such as Seismic Qualification. Palast often gets help in his investigations from whistleblowers and others with inside knowledge or secret documents to share. In this case the sources are insiders who have worked with nuclear emergency diesels.

In a crisis, one source explains, they must go “from stationary to taking a full load in less than ten seconds.” In addition, plant operators often “turbo-charge” diesels rather than buy more. At least two diesels failed at Fukushima before the tsunami hit, he learns. “What destroyed those diesels was turning them on. In other words, the diesels are crap,” Palast writes.

“There is no way those generators can fire up,” he continues, then backs up a bit. “Actually, maybe a 50 percent chance. In nuclear power, the problem is always something cheap. There are three things involved in every plant: cement, steel and fraud.”

It’s a bold charge, and he has documents to back it up. Asked whether this extends to Entergy, owner of Vermont Yankee, he recalled investigating the company for the City of New Orleans, in the days before he became a journalist. Palast studied economics with Milton Freidman at the University of Chicago before striking out as a corporate crime investigator.

“I went through their books and found a corrupt cesspool,” he says. “The NRC calls the standard ‘management integrity.’ They don’t have it.”

In the book, he puts it this way: “I have investigated dozens of nuclear operators, and in every case, no exceptions, I found this: Fraud is as much a part of the structure of a nuclear plant as the cement and steel.”

Shouting from across the water

Palast chronicles the trail of greed and disaster that follow in the wake of finance vultures. The book is fun, despite the grave subject matter, because of his deft mixture of outrage, bravado and self-deprecating humor. Palast is a clever and generous storyteller, and he gives full and frequent credit to a globe-hopping team that includes the beautiful and seductive Ms. Badpenny.

The plot has many twists, so it’s possible to lose sight of the main subjects. Goldfinger, for instance. “There really is a Goldfinger,” he says, “and compared to him the movie villain was a girl scout. The vultures get their hands on money that they claim is owed by the poorest nations, usually during a civil war. Then they find loopholes and seize all the wealth.”

In the book’s opening chapter Palast describes how he uncovered that the real Goldfinger, also known as Michael Francis Sheehan, “bribed the President of Zambia with $3 million. In return he let Goldfinger collect a phony debt and take $45 million off the Zambian treasury – the money we gave them to fight AIDs. This is also a crime.”

Later, investigating the Gulf oil disaster leads Palast to the Whitney Bank, the JP Morgan of the Gulf Coast, and its former president R. King Milling, who connects Big Oil with Big Banking and Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal’s wasteful Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. “The man is the maestro,” Palast concludes. “He has figured out how to completely control the terms of the debate.”

Back in London, Palast tracks down a secretive group of banking and insurance leaders ever hungry for deregulation. They used to be known as the Unnamables, until the BBC outted them and the name was changed to LOTIS, short for Liberalization of Trade in Services. One of its leading members is Peter Sutherland, in some circles called “the father of globalization.” Founding Director-General of the World Trade Organization, once a chairman at both Goldman Sachs and BP, Palast sees him as “the Energy-Finance Combine in one bespoke suit.”

What’s it like to confront someone like that? “I find that the government guys are just careerists. But the actual vultures are brilliant and frightening, and most are fairly charming,” Palast says. “You really have to know your stuff, and not get charmed. Think back: How many news guys licked the loafers of Ken Lay?”

In the interview, we were back to his disdain for lazy reporting. On the other hand, Palast prefers his role as a journalist to his earlier career as a professional investigator digging into financial misdeeds.

Making the change was necessary, he says. “What was the point of doing this, I thought, when I had to dump stuff in a file and seal it? I was going insane, not being able to make this public.

“Going public is vital to me. In London I am on the front page, and all over Europe and Africa. Here I can barely get on the radio,” he laments. “But at least I can shout from across the water, as opposed to not being able to say anything because it’s under seal.”

Despite years of exposing an economic system in which finance vultures devour whole countries, where “donor nations” like Switzerland, Norway, Britain and the United States actually make a killing on collapsed economies, and where the Energy-Finance Combine collects the biggest spoils, Palast nevertheless finds reasons for optimism.

That’s because of the courageous people like those he introduces in the book, as well as the leaders of countries like Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela that have blocked international financial speculation and avoided the worst of the recent crisis.

In the end, “The problem is religious, and this is a religious book,” he says, with just a hint of irony. “These are matters of faith and personal courage. That’s the story I’m telling. It’s about whether we have the courage not to be slaves, toadies and greedsters.”

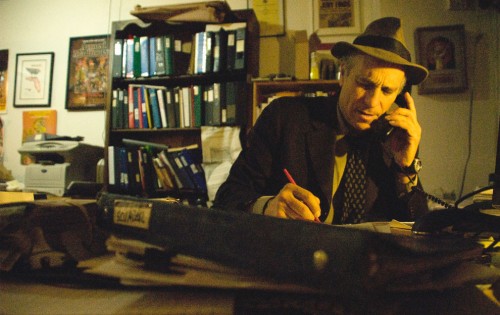

Palast doesn’t resolve that issue, or answer all the questions he raises in the book. But it’s riveting to read or watch – there are video episodes, by the way – as he crosses the planet in trench coat and fedora asking the right questions.

Editor’s note: From 1994-2004 Greg Guma was editor of Toward Freedom, which is sponsoring Palast’s Dec. 12 speaking engagement.