Under the Presidency of José “Pepe” Mujica, Uruguay has made a number of international headlines in recent years for progressive moves such as legalizing same sex marriage, abortion and marijuana cultivation and trade, as well as withdrawing its troops from Haiti. This week, Mujica offered to welcome detainees from the US’s detention center at its base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

The Uruguayan president accepted a proposal from the Obama administration to host the detainees. “They are coming as refugees and there will be a place for them in Uruguay if they want to bring their families,” Mujica explained. “If they want to make their nests and work in Uruguay, they can remain in the country.”

“I was imprisoned for many years and I know how it is,” he said. The left-leaning president is a former revolutionary guerilla who was jailed for 14 years before and during Uruguay’s 1973-1985 dictatorship. After his release, he ended his guerilla activities and entered politics, becoming the Minister of Agriculture in 2005 under the Tabaré Vázquez administration, and was elected to the presidency in 2010.

Mujica, who has been touted as the “world’s poorest president” due to his frugal lifestyle and the fact that he donates about 90% of his presidential salary to charities and social programs, still lives on a flower farm with his wife outside the capital, and drives a beat up Volkswagen Beetle to work. Earlier this year, he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for his progressive marijuana legalization program and views against excessive consumerism. His newest move against the human rights abuses of the “war on terror” has put him back in the global spotlight.

Standing Against a Symbol of the “War on Terror”

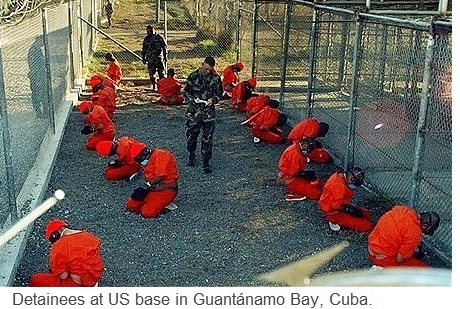

The detention center at the US base in Guantánamo Bay has long been a symbol of the human rights abuses that have come to define the so-called “war on terror.” After 9/11, the George W. Bush administration began using the facility to detain suspected terrorists. It quickly became notorious as a site of inhumane treatment, torture, and lawlessness; a decade later, many of the detainees have been held without charges or a trial.

Roughly 800 men and boys have been kept in Guantánamo as part of the US’s terror suspect roundup. Now only 154 remain, and the Obama administration, with support from Congress, is trying to make good on its promise to shut the detention center down. As part of those moves, Washington is seeking new countries to host the released detainees.

Uruguay is the first Latin American nation to accept Obama’s offer to welcome former prisoners onto its soil. Since Obama’s election, 38 Guantánamo detainees have been released to their home countries, and 43 have been resettled in 17 other countries. According to Human Rights Watch, the US wants to send detainees to countries that can provide the security the US seeks under the terms of the transfer. Uruguayan press reports that the transfer would likely involve five detainees who would have to stay within Uruguay for at least two years.

While Mujica and the US Ambassador are clear that the plans surrounding the transfer are not finalized, Mujica’s reasons for hosting the men are a sign that Uruguay is taking important steps toward justice against Washington’s long-standing “war on terror.”

While Mujica and the US Ambassador are clear that the plans surrounding the transfer are not finalized, Mujica’s reasons for hosting the men are a sign that Uruguay is taking important steps toward justice against Washington’s long-standing “war on terror.”

For years, countless activists, governments and human rights groups have called for the closure of the US detention center in Guantánamo Bay. Last July, activist Andrés Conteris, who has worked for decades on human rights issues in Latin America,went on a hunger strike for over three months in solidarity with hunger-striking prisoners in Guantánamo Bay.

The strike denounced the inhumane and unlawful treatment of the detainees; numerous cases of physical, psychological, religious and medical torture against prisoners have been widely reported over the years. It is this treatment that President Mujica is standing against in his welcoming of the detainees.

“Given Pepe Mujica’s experience with long-term torture,” Conteris explained to me, referencing Mujica’s own imprisonment, “this gesture offering to resettle Guantánamo prisoners in Uruguay not only expresses his country’s commitment to human rights, but it shows a personal connection this president has with those suffering inhuman treatment perpetrated by military forces.”

***

Benjamin Dangl has worked as a journalist throughout Latin America, covering social movements and politics in the region for over a decade. He is the author of the books Dancing with Dynamite: Social Movements and States in Latin America, and The Price of Fire: Resource Wars and Social Movements in Bolivia. Dangl is currently a doctoral candidate in Latin American History at McGill University, and edits UpsideDownWorld.org, a website on activism and politics in Latin America, andTowardFreedom.com, a progressive perspective on world events. Email: BenDangl(at)gmail(dot)com.