When I was asked if the community radio station I’m involved in would like to co-sponsor an event with legendary zinesters Erick Lyle (aka, Iggy Scam) author of Scam and Cindy Crabb (Doris), I enthusiastically signed us on right away. Before their reading at Food For Thought Books Collective in

Matt Dineen: How do you usually respond when people ask you, "What do you do?" What does that question mean to you?

Erick Lyle: What do I do? Well, I guess I’ve always felt like I’m a writer since I was a little kid. It’s how I see the world-in terms of being a writer. I don’t ever take pictures of things on vacations and stuff like that. I’m always just describing things in my head. I think writing informs my basic interaction with the world. And I’ve never thought of myself as an activist and all that, but I have always thought of myself as a writer.

MD: Can you talk about living in

EL: Well, it depends on what you call work. I haven’t had a real, straight job in almost 20 years, but I live in one of the most expensive cities in the country to live in. So this is the paradox. I would say that I’m part of a community of folks in

In the book I talk about this street newspaper I used to do called, The Turd-Filled Donut with my best friend Ivy. We were putting out this skid row newspaper, living in welfare hotels and writing about the neighborhood, trying to highlight people’s struggles: for tenants to organize against their shitty hotel owners, or for homeless people who were organizing to demand housing and things like that. We spent hours, all the time working on this paper, interviewing people, editing the paper, getting art for it, putting it out on the streets. It was a free newspaper. We gave it away. So that’s work, but it’s not work for financial remuneration.

That’s kind of the subject of my buddy from San Francisco Chris Carlsson’s new book [Nowtopia], how people are looking for community and meaningful work outside of, let’s say, wage slavery. You know, most of the work that people are doing is completely meaningless and is not benefiting themselves or each other or the planet. It’s just totally busy work and people are really dissatisfied with it. So there are all kinds of folks that are willing to work themselves to the bone 25 hours a day for what they believe in I haven’t had a service industry job or something for a long time. The last real job I had was in 2000, I worked at a queer youth homeless shelter. That was the last "official" job I had. Since then, it’s been freelance writing, crime, things like that make ends meet. That’s how it is. But always working on other stuff like putting on punk shows, protests, putting out a magazine that doesn’t really pay for itself.

MD: I think that element of community is so important, like the one in San Francisco you are part of, and relating that to the social pressure that a lot of people who don’t have a community like that face. They can have these ideas, wanting to work on their own projects, doing things that aren’t completely defined by a status job. But then they have pressure from their families, the larger society and just the economic realities of daily life. And that can be challenging even for people who do have really supportive communities.

EL: Yeah, I mean, things are awful right now with the economic situation We’re so far from changing things. We’re sitting next to a freeway onramp. Everything is geared toward people having to drive everywhere they need to go. The food’s being trucked in. The wage level is so low. The work is unskilled. People are working practically minimum wage. They need two or three jobs to make it. The economic situation in this country definitely makes it so that people are totally alienated and isolated. It’s very cutthroat. It’s an awful situation.

Some things you see are positive examples, like tonight we had an event sponsored by several collectives. People have come together to collectivize their workplace. That’s one step in a positive direction. Is that gonna happen everywhere? I don’t know. I don’t think that invalidates the work that my community does, to say that we don’t have an answer for how to get out of Wal-Mart or something. I know there are movements nationwide of people trying to hold these chain stores accountable for their labor practices, for their environmental practices.

MD: At the event you mentioned the importance of vision, of describing and putting into practice the kind of world we do want to be living in. So in the context of how messed up things are do you want to talk more about that and maybe relate it to the examples given in Chris Carlsson’s book?

I think Chris did a good job of highlighting that in Nowtopia. He just went around trying to find examples of that impulse in people. He talked about community gardens and bike projects where people are trying to find that community in some shared prospects. I think that stuff is really good and I think what would be really powerful would be for people to take that a little further. It’s hard to really name what I’d like to see because it doesn’t exist exactly, but sort of community groups that come together to do things that are anti-war, for instance, but incidentally anti-war. People that are coming together to do a food program in their neighborhood, to share food and health care resources and they’re meeting all the time and talking about issues-something that’s like a Black Panther model of a free breakfast program. You get people taking care of each other and then that’s a strong platform to work from to be like, "And yeah, we’re against this war and we’re against this displacement in our community." You find something that people can rally around. I don’t know, those are the historical examples I’ve looked for and I think Chris is trying to find stuff that is happening now that also show this really intense longing that people have. And Cindy, in her piece tonight, talked about that.

Like every time there’s a natural disaster you see this wave of people suddenly organized into this help-mode. Or, people say that after September 11th in

MD: You mentioned that you don’t really identify as an activist, but you’re talking about these more practical ways that people can create a vision for a better kind of society. How do you see your role as a writer fitting into that?

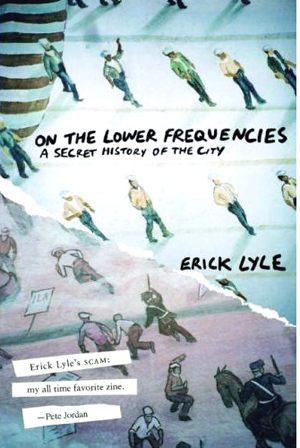

EL: Well, I think that writers and artists have always been in a position to imagine a different world and push this one in a different direction. In my book, On the Lower Frequencies, I write about a mix of people that are organizing together. It’s a combination of artists, activists, and writers. It’s not so defined. So like when you have people come together and take over an abandoned building, like 949 Market, and create this presentation where everything is present. We had collaborative murals that encircled the space instead of art gallery work, which is all about the individual artist. You know, in art shows artists aren’t expected to work together. They’re supposed to work competitively and sell there stuff. So we had people working collaboratively. All of our events always had free food because we felt like there was no space in our city for people to get together and enjoy food together. And that’s a really important thing, just to have that time and space. That’s the kind of place that’s gonna create community and help new ideas to develop. And it’s really basic but, everybody’s really overworked, it’s really expensive, there’s no time, and real estate’s not there so we don’t have that kind of space. So we always provided food and we think it’s important to have these musical and artistic representations of the world we’re trying to live in. Artists and writers have always done that.

I feel like some of these protests that are described in the book also function as art in a certain way because the idea is to sort of change people’s consciousness, to get people to think about things differently as well as to do practical things like take over a space and use it. So I hope that’s what people will get out of the book, especially more mainstream folks who may read it. I hope what they’re gonna get out of it is that maybe they’re gonna look at the city in a different way. They’re gonna see people on the street and not instantly be against them for panhandling and things like that. They’re gonna see empty buildings and people on the street and they’re gonna think about their relationship.

Also, the book is about lost moments from history. When there have been these moments when people have come together to do really important stuff and then maybe there’s a revolt, it gets crushed, or a squat that gets closed, or a movement that dies out, people try to take the message from it that it’s a failure. And I would suggest that history also works like art in that, these historical moments suggest a different path we could’ve taken. They ask a question that has yet to be answered. They still show a way to a different world. And those examples are also out there for people to look at and think about a different future. So that’s part of what writing and research can do as well.

***

Matt Dineen is a writer and the host of Passions and Survival, a weekly program on Valley Free Radio in