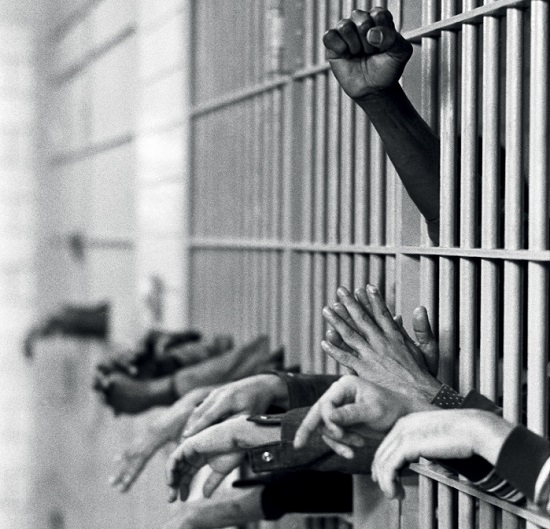

There is a widespread, growing and committed resistance movement happening in US prisons across the nation. This movement is not going away, and with more outside support and national coordination, it could be powerful enough to reshape not only the US prison system, but the entire society.

At the time of this writing thirty prisoners at Ohio State Penitentiary, the supermax prison in Ohio are recovering from a hunger strike that has lasted over 30 days. Prisoners in Georgia, accused of leading the largest prison work stoppage in US historyin 2010 are on hunger strike demanding relief from torture conditions they’ve been subjected to in solitary confinement as reprisal for their non-violent protest. The Free Alabama Movement (FAM) has been dealing with threats, beatings and lockdowns they’ve been subjected to in reprisal forthe mass work stoppages that shut down three Alabama facilities for weeks in January of 2014.

Massive hunger strikes that rocked California’s prison system in recent years are now getting slow results in favorable court decisions for their class action lawsuit. Prisoners in Illinois, Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina and Washington Statehave all engaged in historically large protests in recent years. In February, thousands of immigrant prisoners in a federal detention facility in Texas refused to work, and protested and sabotaged the facility, rendering it uninhabitable. At around the same time women at an Arizona county jail were on hunger strike refusing to eat the moldy food they’d been served.

The above examples are only the most coordinated and best publicized of these protests. Many prisoners see individual acts of courage and resistance as necessary for their identity and survival. When the country locks up as large a portion of its population as the US does, prisoner protests are inevitable and almost constant.

The demands of these protesting prisoners are myriad, specific, complex and overlapping, just like the repressive bureaucracies they struggle against. From medical neglect, to wrongful conviction, or sexual assault and violence committed by staff members (particularly in women’s facilities) prisoners have many good reasons to protest and rebel, and many harms and traumas to recover from.

Prisoners engaged in the larger movements like FAM, or the CA hunger strikes also have many personal and individual grievances, but they have come together to form coordinated mass protests with collective demands. These demands vary, but can be categorized into two broad calls for justice: to end prison slavery and to end torture.

To End Prison Slavery

The thirteenth amendment to the US constitution does not abolish slavery. It states: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction” (my emphasis). All prison systems in the US rely on prisoner labor to maintain the facilities. It is prisoners who mop floors, fix plumbing, handle paperwork, and do the many other tasks necessary to keeping the prison running. Prisoners are also farmed out to private corporations seeking cheap labor. All this labor is grossly underpaid (if paid at all) and compulsory; as many prisoners have explained to me, it is a modern form of slavery.

One important step toward ending prison slavery is to allow prisoners to organize labor unions. Prisoners need to be able to strike without violent reprisals, and to negotiate for improved conditions, including health, safety, conditions and wages. A robust and legally protected prisoner’s union is the strongest protection against inhumane and intolerable slavery conditions in prisons.

Prisoners have been fighting for labor unions since the seventies and the US Supreme Court has consistently deferred to prison administrations, rather than defending the basic human rights of incarcerated people. The 1977 decision in Jones v North Carolina Prisoners’ Labor Union, Inc. establishes the controlling precedent. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union has taken up the call of prisoner organizing, forming an Incarcerated Workers’ Organizing Committee, whichworks closely with FAM prisoners, as well as prisoners in other state systems.

The most powerful form of direct action prisoners have used to demand the right to organize and to end slavery is a work stoppage.

To End Prison Torture

Prisons across the US rely on various forms of terroristic violence and coercion to maintain control. Prison administrators’ options vary from pepper spray, electrocution, beatings, and restraint positions, to medical neglect, deprivation and isolation. The form of torture that has gotten the most attention, and the strongest opposition from prisoners and their supporters in recent years, is solitary confinement.

In June of 2012 US Congress held their first hearings on solitary confinement. Anyone paying attention heard heartbreaking testimony from Anthony Graves, an exonerated Texas prisoner who experienced and witnessed the destructive effects of long term isolation on prisoners.

According to SolitaryWatch.com,US prisons hold over 80,000 prisoners in solitary confinement on any given day at a cost of $75,000 per prisoner per year. Many are held in isolation for years, or even decades. The prison system spends this money and trouble because they depend on solitary confinement as a tactic to break up organized groups and prevent rebellions.

Ending Slavery and Torture

These demands are directly related to each other. When prisoners get organized, the prison responds by locking up leaders, or arbitrarily choosing people to make examples out of in isolation. Solitary confinement is both a tactic for breaking up strike organizers, and a deterrent to prevent prisoners from participating in these actions. After beating striker Kelvin J. Stevenson with a hammer, Georgia prison authorities put him in solitary for what is now over five years; he is participating in the current hunger strike.

Siddique Abdullah Hasan, a long time prison rebel in Ohio, who has been in solitary confinement for over two decades has called for a nationally-coordinated prisoner protest, including hunger strikes and work stoppages. Prisoners have shown a commitment to protesting against severe and often violent reprisals. Hasan believes that, like the California hunger strikes a few years ago, many prisoners would join the movement once it took off.

The missing link is outside support. Without pressure and scrutiny from the outside, prisoners engaging in these struggles can face severe and often illegal consequences. Those of us with access to media and policy makers, with robust social networks and the ability to make public spectacles at the offices of prison authorities or elected officials are essential to prisoners reaching their goals. The Free Alabama Movement recognizes this and has outlined a step by step process by which local organizers can connect with prisoners and demonstrate our strength and commitment to support, allowing prisoner organizers to predict the possibility of success for their actions on the inside.

Even with outside support these will be extremely fierce battles. Prison administrators consider prison labor and isolation as existentially important to the operation of their institutions. Without slaves to maintain their facilities, the costs of prison will skyrocket. Without solitary confinement and supermax facilities dedicated to further isolating “trouble-makers,” they fear their captives will get organized and defend themselves. These fears are probably well founded. The increased reliance on supermax prisons and other forms of long term solitary confinement has correlated with a decline in prison riots and uprisings.

US prisons will need to transform drastically to survive without slavery and torture. Rather than being places of punishment, repression and control, they will have to maintain order by appeasing prisoners and meeting their needs. Prisons will have to become locations for support and healing, they will have to live up to the “rehabilitation” and “correction” their department names often falsely promise. They will surely no longer be able to house a quarter of the world’s prisoners as they do today.

US prisons may not be able to handle these changes; the current administrators almost certainly won’t. That is not our problem. If prisons cannot run without slavery and torture, then they should not run. Mass work stoppages and hunger strikes, with outside direct action support will make prison financially untenable. We will shut the prisons down. If the increasingly unequal and largely illusory class peace of American capitalismcannot survive without its prisons, then it too should and will end. We can and will abolish slavery and torture in US prisons, along with them we will bring down whatever institutions depend on these intolerable practices.

More information and organizing opportunities:

Free Alabama Movement: An organization led by Alabama prisoners looking to abolish slavery through work stoppages at prisons across the country: https://freealabamamovement.wordpress.com/

Solitary Watch: News from a Nation on Lockdown: http://solitarywatch.com/

IWW Incarcerated Workers Committee: Organizing for Workers Behind Bars: https://www.facebook.com/incarceratedworkers

Support Prisoner Resistance: Interviews with prison rebels on organizing tactics: http://supportprisonerresistance.noblogs.org/

Ben Turk is a dedicated prison abolitionist and the co-founder of the anarchist theatre troupe Insurgent Theatre (insurgenttheatre.org). His prisoner support work focuses on the survivors of the Lucasville Uprising (LucasvilleAmnesty.org), and prolific anarchist firebrand Sean Swain (SeanSwain.org).