Introduction

Pan-Africanism is one area that African academics have shied away from for some time now. For this reason, faculty and students, across the continent, have little understanding of what it really means, and especially, when it started, and for what purpose. It is therefore important that African higher education institutions revisit the issue to place it back on the continental agenda because it is experiencing a resurgence.

Consequently, there is the need to show its importance and the significant contribution it made to African history, especially, the first major 1958 All-African People’s Conference. This has necessitated the attempt to look at the subject through the prism of the Zone Analysis Theory.

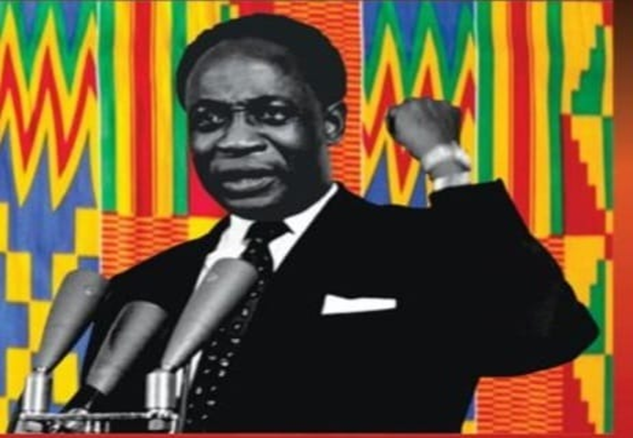

Pan-Africanism, born in the Americasis a phenomenon, which promotes freedom, unity, oneness and solidarity on the spiritual, cultural, social, political, and economic levels, social and racial justice, and self-determination of people of African ancestry. This movement won its first electoral and political victory in Africa in 1951 when Kwame Nkrumah, a staunch Pan-Africanist, became head of government business of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) after winning an election while in prison1. Ghana became independent on March 6, 1957, as the first country in black Africa to rid itself from the shackles of colonialism.

One year after its independence, Ghana hosted two conferences, respectively for the already independent nations: the Conference of Independent African States and for the freedom fighters, i.e. the All-African People’s Conference. The latter was impactful and consequential. It was an inflexion point in the history of Africa. It ignited Pan-Africanism and accelerated the decolonization process.

In this article, I seek to discuss the success of the All-African People’s Conference, which took place December 8-13, 1958, through the prism of a Pan-African theory: the Zone Analysis Theory. While much of the literature in the field of Pan-Africanism is often done from a historicist perspective, I want to refocus our discussions of Pan-Africanism through theorization. A theory is an ideational framework—based on observation, interpretation, and everyday dynamics—that can elucidate historical, political, and cultural realities and can guide action and movements.

Africa could not host major Pan-African meetings before the independence of Ghana—it is for this reason that most of the Pan-African gatherings before the All-African People’s Conference took place outside the continent of Africa. Using the fundamentals of Nkrumah’s ideas, which were further developed by Zizwe Poe, I examine how a Pan-African liberated zone contributed to the expansion of Pan-Africanism and to the creation of Pan-African communities of struggle and shared thought—in short, Pan-African liberated zones.

The zonal analysis tenets were outlined by Kwame Nkrumah in his book Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare published in 1968 while he was proposing guidelines for successful revolutions in Africa. He divided Africa fighting for its freedom into three zones: liberated zones, contested zones and enemy-held zones2. Zizwe Poe used some of the above-mentioned tenets to highlight the significance of independent Ghana as a free zone, a liberated one, which contributed to the advancement of Pan-Africanism, in his book Kwame Nkrumah’s Contribution to Pan-Africanism. He later articulated the Zone Analysis Theory in 20123.

My analysis here will proceed in three parts. The first part discusses the origin and the fundamentals of the Zone Analysis Theory. To better explain the relevance of that Theory, I demonstrate in the second part of the study why most of the Pan-African gatherings, which took place before the independence of Ghana took place outside the continent of Africa in European capitals. The third part of the text examines the significance of the independence of Ghana and how it created the space that ignited Pan-Africanism in Africa and enabled the organization of a new series of Pan-African gatherings called the All-African people’s Conferences.

Zone Analysis Theory, a Pan-African Theory

The process of the Zone Analysis Theory formation can be divided into three steps: Kwame Nkrumah’s zonal classification, Zizwe Poe’s interpretation of Ghana’s independence as a liberated zone and his primary zonal theory articulation and my own contribution, which is providing a comprehensive definition of the Zone Analysis Theory and the categorization of the same theory.

The Zone Analysis Theory finds its relevance in relation to the historical context of colonization. The founding act of colonization was the Berlin Conference (1884-1885). It sealed the partition of Africa on paper. The golden rule adopted by the participants during the conference could be summed up in these terms: Any territory already occupied or conquered belongs to the conquering country’.4 By the beginning of the twentieth century, the entire continent of Africa, with the exception of Ethiopia and to a lesser extent Liberia created by the American Colonization Society for freed American slaves, was under colonial rule. Ethiopia was the only African country to have escaped colonialism after defeating Italy twice respectively at the Battle of Dogali in 1887, under Yohannes IV and at the Battle of Adwa in 1896 under Menelik II. 5

Events have had an impact on the decolonization of Africa and on the evolution of Pan-Africanism, namely World War II (WWII), the creation of the United Nations in 1945 and the Bandung Conference, which took place in 1955. The British colony of the Gold Coast (Ghana) became independent on March 6, 1957, through peaceful means.6 The war of independence of Algeria erupted in 1954 through an armed struggle. The Sharpeville Massacre of November 1960 led to the killing of 69 unarmed people. Freedom fighters were engaged in a series of armed struggles across the continent of Africa, from Southern Africa to the Portuguese colonies. Kwame Nkrumah himself was overthrown on February 24, 1966. In his Conakry years in exile, he published a manual of guerrilla warfare, Handbook Revolutionary Warfare: A Guide to the Armed Phase of the African Revolution, which provides the tools for the articulation of the Zone Analysis Theory. In the context of a revolutionary warfare, Kwame Nkrumah provides a classification of zones:

For although the African nation is at present split up among many separate states, it is in reality simply divided into two: our enemy and ourselves. The strategy of our struggle must be accordingly, and our continental territory considered as consisting of three categories of territories, which correspond to the varying levels of popular organisation and to the precise measure of victory attained by the people’s forces over the enemy:

1. Liberated areas

2. Zones under enemy control

3. Contested zones (i.e. hot points).7

The three zones (liberated zones, zones under enemy control, and contested zones) become the foundational pillars of the theory. Kwame Nkrumah goes on to argue that in a liberated zone, freedom is attained and obtained through a successful struggle or through a successful coup d’etat that can take out of power a neo-colonialist regime.8 Kwame Nkrumah suggests a strong cooperation between liberated zones and the liberation movements in the contested zones and in the enemy-held zones.9

The zones under enemy control or the enemy-held zones are completely subjugated and totally controlled by the oppressors, settler colonists, colonizers or neo-colonists who control all aspects of life of these zones, namely political, economic, cultural and military.10 The Ghanaian leader asserts that the revolutionary awareness of the masses determines the fate of the struggle. If and when it is high it is likely to lead to resistance, to « national boycotts, strikes, sabotage, and insurrection. » 11 Enemy-held zones can be easily transformed into contested zones if the revolutionary spirit can spark a successful revolt. Contested zones are transition zones that can be placed between the enemy-held zones and the liberated zones. In these zones, the oppressed and the oppressor are engaged in a battle, which determines if freedom can be attained or if oppression continues.

Building upon Kwame Nkrumah examination, Zizwe Poe, in his book Kwame Nkrumah’s Contribution to Pan-Africanism: An Afrocentric Analysis, emphasizes the significance of Ghana’s independence to the expansion of Pan-Africanism. He demonstrates the significance of the Ghanaian independence and presents Ghana as an example of a liberated zone or as « a Pan-African liberated zone.12 » Zizwe Poe stresses that the primary goal of Ghana as the first Pan-African liberated zone was to help create or transform other colonies or free nations into Pan-African liberated zones. 13 Zizwe Poe defines a liberated zone as « a zone from which to launch and support liberation. »14

In order to highlight the optimal dimension of Ghana as a purposive true Pan-African liberated zone, Zizwe Poe compares three liberated zones such as Haiti, Liberia and Abyssinia (Ethiopia), He presents the latter as a Pan-Africanist symbol of a liberated zone.15 He differentiates these Pan-African clusters from Egypt, which was a liberated zone but not a Pan-African liberated one from the outset. Egypt later evolved to turn into a Pan-African liberated zone. 16 Zizwe Poe echoes the position of Vincent Bakpetu Thompson who declares that Ghana then offered what Liberia and Ethiopia could not provide: a safe-meeting place for the discussion of priorities.17 Thompson would also argue that in 1957 Ghana was the first to be independent in Black Africa and was therefore rightfully viewed as the beacon of hope, freedom, and unity of African nationalists.18

Building on what precedes, I now define the Zone Analysis Theory as a Pan-African Theory through which one can measure the environmental freedom of a given people in a given society, the level of revolutionary awareness of the elite and of the masses, and the degree of sovereignty of the agency in a specific zone. From this definition it is clear that there are three dimensions which are the three components of the zonal theory: environmental freedom, revolutionary awareness or consciousness, and sovereignty of agencies. These three dimensions can be discussed in each of the three zones: liberated zones, contested zones and enemy-held zones.

In the next section, I discuss the theory against the backdrop of the venues of the Pan-African gatherings before the independence of Ghana.

Zone Analysis Theory and Venues of Pan-African Gatherings before Independent Ghana

The colonial settlers set up a system of colonial administration that did not guarantee basic freedoms, especially freedoms of assembly, association, and organization. This explains why most of the Pan-African rallies took place in the western cities: London, Paris, Lisbon, Brussels, New York, Manchester. Besides the major Pan-African political organizations such as the African National Congress (ANC) created in 1912 in South Africa and the Rassemblement Democratique Africain (RDA) created in Bamako (French Sudan now Mali) in October 1946, the attempts to organize Pan-African gatherings before the independence of Ghana were marginal.

Joseph-Casely Hayford was the main architect in 1920 of the establishment of the National Congress of British West Africa (NCBWA) whose goal was the building of West African unity in Accra. Delegates from the British colonies in West Africa (Gambia, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast- Ghana, Nigeria) took part in the meeting. The NCBWA suffered the contempt and derision of the colonial authorities, but nevertheless succeeded in pursuing its mission, by organizing rotating congresses in the British colonial capitals of West Africa. The NCBWA organized four Pan-African Congresses between 1920 and 1930. The third was held in Bathurst in The Gambia in December 1925. The last was held in Lagos in December 1929.19 Apart from these meetings, the major Pan-African meetings took place outside the continent of Africa.

The first acclaimed Pan-African conference took place in July 23-25, 1900, in London under the leadership of Trinidadian Henry Sylvester Williams in the midst of the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was the champion of the Back to Africa movement in the early years of the 20th century. He was credited to have transformed Pan-Africanism into a mass movement. His gatherings called conventions mobilized tens of thousands of Black people. The headquarters of his organization was Harlem in New York.20 Marcus Garvey could not visit Africa as he was prevented from doing so by colonial forces. W.E.B. Du Bois, who was at the London conference, initiated another series of Pan-African gatherings that he called Pan-African congresses. They took place in 1919, 1921, 1923, 1927 and 1945; all in western cities and capitals. The first congress took place in 1919 at a historic moment and in a symbolic city for the context. It was the end of World War I and Paris was chosen because of the Treaty of Versailles about to be signed in the suburbs of the French capital. The second Pan-African Congress took place in 1921 in London, Brussels, and Paris. A third of the participants were from Africa. The Third Pan-African Congress was held in 1923 in London, Paris, and Lisbon. The Fourth Pan-African Congress of 1927 was held in New York. It was supposed to take place in the Caribbean. W.E.B. Du Bois explained why the organizers initially wanted to organize it in the Caribbean: “So far the Pan-African idea was still American rather than African, but it was growing and it expressed a real demand for an examination of the African situation and a plan of treatment, from the native point of view. With the object of moving the centre of that agitation nearer African centres of population.” 21 He pursued to explain how he intended to organize that meeting, and he accused colonial powers of having thwarted it: “My idea was to charter a ship and sail down the Caribbean, stopping for meetings in Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba, the French Islands. Here I reckoned without my steamship lines. At first the French Line replied they could easily manage the trip;’ but eventually no accommodations could be found on any line except at the prohibitive price of fifty thousand dollars. I suspect the colonial powers spiked this plan.”22 The African centres of population namely Haiti, Cuba, the French Islands were all according to the Zone Analysis Theory non-sovereign territories and enemy-held zones.

Eventually New York was chosen because the organizers wanted to highlight the issue of racism in the United States and the growing importance of that country in the world. The congress brought together 208 delegates from 22 American states and 10 foreign countries. Africa, however, was poorly represented with delegates from the Gold Coast (Ghana), Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Nigeria.23 The small number of African delegates was partly due to travel restrictions imposed by the British and French colonial powers on those who expressed interest in attending the congress. The travel restrictions prevented a massive turnout of African delegates. Most of the Black American delegates were women. As at previous Pan-African congresses, participants discussed the status and conditions of Black people across the world.

The Great Depression of 1929 and the military imperatives generated by WWII led to the suspension of Pan-African meetings for a period of eighteen years.24 Under the leadership of W.E.B. Du Bois, Pan-Africanists sought to organize the fifth Pan-African Congress in Tunis, as they wanted that Pan-African gathering to be « geographically African. » 25 The French colonial power, which had Tunisia as a colony, would only allow that Pan-African meeting to take place in Marseilles, another French city. The fifth Pan-African congress finally took place in Manchester from October 15 to 21, 1945. W.E.B. Dubois was appointed chairperson of the gathering whose main organizer was Trinidadian George Padmore aided by Kwame Nkrumah.

The Zone Analysis Theory, Ghana Independence, and the Significance of the All-African People’s Conference

The systems of domination such as colonialism, segregation, and apartheid were repeatedly scorned at the United Nations created in the aftermath of WWII.26 As a result of his resounding victory in 1951, while in prison, Kwame Nkrumah was released from prison and formed a government in which were four British and seven Africans.27 The leader of the newly independent country organized in 1953 a Pan-African conference in Kumasi (Gold Coast). The gathering launched the idea of forming an independent West African Federal State.

The meeting could not claim to be representative of the African masses given the non-participation of leading figures in the fight for the decolonization of Africa. Nkrumah intended to organize another Pan-African conference in 1954. That one could not take place. It was not until the independence of Ghana that major Pan-African conferences were held on the African continent, particularly in Accra (Ghana). 28 Ghana gained its independence on March 6, 1957 as the first Sub-Saharan African country to be free and the first Pan-African liberated zone as envisioned by the Manchester Congress. The correlation between the independence of Ghana and that of the African continent was beautifully illustrated by Kwame Nkrumah himself during his midnight speech on March 6, 1957: « The independence of Ghana is meaningless unless it is linked up to the total liberation of the African continent. »29

These remarks articulated a Pan-African doctrine. Ghana became a magnet and a safe haven for African nationalists and freedom fighters seeking refuge, guidance, and assistance. Ghana also became a coordinating centre for Africa’s decolonization and unity. Its leader, Kwame Nkrumah, took upon himself to bring together African leaders, African nationalists and the representatives of African masses fighting for freedom to accelerate the pace of decolonization.

The Conference of Independent African States brought together independent African states such as Ethiopia, Tunisia, Morocco, Egypt, Libya, Liberia, and of course Ghana. The goal was to coordinate efforts and strategies for the decolonization of the continent of Africa.30 The last words “Hands off Africa! Africa must be Free!” of Kwame Nkrumah’s inaugural speech during the Conference of Independent African States became the slogan of the All-African People’s Conference, coordinated by George Padmore, who was assisted by a preparatory committee.

After the Conference of Independent African States, Kwame Nkrumah visited the leaders of the countries who participated in the meeting in their respective countries. This helped strengthen physical contacts as a practical means of unifying African countries. In a context of bubbling ideas and possibilities for action, mobility among Africans has increased. Nkrumah had thus set the tone.31

Some other Pan-African gatherings took place in 1958 respectively in Tanganyika (September), Cotonou (July). The meeting in Tanganyika saw the creation of the Pan-African Freedom Movement for East and Central Africa (PAFMECA). Cotonou gave birth to a Pan-African party in favour of independence, the Parti of Regroupement Panafricain (PRA). Even though important, they could not be compared in magnitude, symbolism, and impact to the All-African Peoples Conference of December 1958 in Accra, which was a consequential event.

I will spotlight now how the All-African People Conference of 1958 used the three dimensions of the Zone Analysis Theory, environmental freedom, revolutionary awareness of the freedom fighters, and sovereignty of agency to promote Pan Africanism and freedom in Africa. Under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah and the Convention of People’s Party, the masses namely the women, the youth, the trade unionists, the farmers had been awakened. Several organizations and structures were created to be the channels of the struggle and sentinels of the revolution and to contribute to the ideals of freedom and unity across the continent: the National Council of Ghana Women (NCGW), the Young Pioneers, the Ghana Trade Union Council (G-TUC) and the Ghana Farmer’s Council.

To carry out the actual and practical organization of the Pan-African gatherings in Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah created two specific sovereign agencies: the Office of the Advisor to the Prime Minister for African Affairs and the Centre for African Affairs. The first had the essential objective of working for the liberation and unity of Africa. It functioned as an investigative body, a propaganda platform, and a centre that allowed for the exchange of ideas with African nationalist leaders. This institution provided financial and logistical support to liberation movements in Africa and facilitated the integration into Ghana of the many political exilesto whom it provided logistical support. George Padmore was in charge of the Office of the Advisor to the Prime Minister until his death in 1959. He was the main architect of the All-African People Conference. The second tool, the Centre for African Affairs, was intended to be a reception centre for Pan-African meetings and to be an ideological training centre for African nationalists. Hundreds of them crossed paths there, received their ideological training and learned from each other.32

Hundreds of African nationalists and international observers and partners of Africa gathered and discussed a variety of topics, namely the adequate methodology to achieve independence and notions such as African Personality. The gathering was a revolutionary landmark gathering. The revolutionary significance of the All African Peoples Conference lies in the following: the geographical relocation of the Pan-African Conferences, the naming of the new series of Pan-African gatherings, the change in leadership of the Pan-African movement, the redefinition of the concepts of the African Personality and Pan-Africanism, and in the immediate impactful reverberations and repercussions of the gathering.

The Pan-African gatherings were now held in Africa. They took the name “All-African People’s Conference” instead of congresses or conventions to mark a new cycle of the Pan-African gatherings.33 African leaders were now the leaders of the Pan-African movement rather than people from the Americas. The notions of African Personality (as articulated since the 19th century by Edward Blyden) and Pan-Africanism now transcended the idea of Black identity. They now reflected the multiracial identity of Africa.34 Kwame Nkrumah would therefore claim: In 1958, Pan-Africanism had moved to the African continent, where it really belonged.’35

The Accra calls for independence spread like wildfires across the entire continent of Africa from north to south from east to west, across races, borders, and ideologies.36 Consequently, in 1960, 17 African countries became independent, including the colonies of France in black Africa. Two other iterations of the All-African People’s Conference took place respectively in Tunis (1960) and Cairo (1961). In hindsight, Kwame Nkrumah affirmed that three historical events have contributed to increasing the urge in Africans to be free: The Conference of the Independent African States, which took place from April 15-22, 1958, the All-African People Conference which took place from December 8-13, 1958 and the All-African People’s Conference of 1961 in Cairo.

Conclusion

In this research I have shed light on the significance of the 1958 All-African People Conference that contributed to the expansion of Pan-Africanism which thus reached new heights. A sovereign state, Ghana, conscious of its mission as a liberated zone, led by a vanguard political elite supported by awakened masses created agencies to sustain its freedom and to support others to gain theirs. The primary agencies, besides the Convention of the People’s Party (CPP) were the Office of the Advisor to the Prime Minister for African Affairs and the Centre for African Affairs. Thanks to these agencies which were totally sovereign, Ghana embarked on its mission to free Africa and build its unity. Ghana supported the liberation movements on the African continent and devised a plan for the unification of the continent.

To highlight the importance of a liberated zone in the struggle for freedom, I have demonstrated that the Pan-African Conference under Henry Sylvester Williams, the Pan-African Congresses under W.E.B Dubois, the Pan-African Conventions under Marcus Garvey all took place in European cities. Even some of the Pan-African gatherings organized in western cities suffered from the interference of western powers which sought to either thwart these meetings or to reduce their success by imposing visa restrictions on the delegates.

I also briefly compared the 1958 conference and that of 1953 organized in Kumasi when Ghana was not yet a liberated zone but a contested zone and when most of Africa was still full of enemy-held zones. I have conducted the discussion through the lens of a theory, that of the Zone Analysis Theory. Its foundational pillars were put forth by Kwame Nkrumah himself. Its theoretical articulation was done by Zizwe Poe. I have in this research contributed to that theory formulation by providing a comprehensive definition and its categorization while spotlighting the significance of the All-African People’s Conference in the history of Africa and its people. The zonal analysis can better explain the organization of different types of Pan-African gatherings, those of union leaders, political leaders, women, youth, and those of writers and intellectuals, thus making Ghana live up to its mission of a true liberated zone. The 1958 All-African People’s Conference was a great success because it was organized in a liberated area that was an independent Ghana. Today the elites and the masses of Africa are engaged in another golden age of Pan-Africanism

characterized by the quest for economic sovereignty. Continuing analysis is needed to measure the level of freedom and the state of art of the current revolutionary struggle.

Dr. Gnaka Lagoke is Associate Professor of History and Pan-Africana Studies at Lincoln University (PA) and author of Laurent Gbagbo’s Trial and the Indictment of the International Criminal Court: A Pan-African Victory and Le Panafricanisme d’Hier à Demain et la Philosophie Ubuntu. Email: [email protected]

Endnotes

1George Padmore, Pan-Africanism or Communism (New York: Doubleday & Company, 1971), 156.

2Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare: A Guide to the Armed Phase of the African Revolution (London: Panaf Books, 1968), 44.

3Zizwe Poe, “Reflecting on Pan-African Liberated Zones: Designing a Dynamic Nkrumahist Evaluation”, Conference pronounced at the 24th Cheikh Anta Diop Annual Conference in Philadelphia, October 10-12, 2012.

4Kevin Shillington, History of Africa, Third Edition (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 314.

5Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 67.

6Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 112.

7Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 44.

8Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 44.

9Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 45.

10Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 46.

11Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 47.

12Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 3.

13Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 25.

14Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 162.

15Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 66.

16Zizwe Poe, Contribution of Kwame Nkrumah to Pan-Africanism, 162.

17Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism (New York: Humanities Press, 1969), 126.

18Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism, 124.

19Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism, 47.

20Amzat Boukari-Yabara, Africa Unite (Paris: La Decouverte, 2014), 71.

21W.E. Burghardt Du Bois, The World and Africa: An Inquiry into the part which Africa has played in world history (New York: International Publishers, 1965), 242.

22W.E. B. Du Bois, The World and Africa, 242.

23W.E. B. Du Bois, The World and Africa, 242-243.

24W.E. B., The World and Africa, 243.

25W.E. B. Du Bois, The World and Africa, 243.

26Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism, 126-129.

27Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah, 139.

28Marika Sherwood, “Pan-African Conferences, 1900-1953: What Did “Pan-Africanism” Mean” in The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol. 4, No 10 (January 2012); p. 116-118.XXX

29Ama Biney, The Political and Social Thought of Kwame Nkrumah (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 3.

30Zizwe Poe, Kwame Nkrumah’s Contribution to Pan-Africanism, 109.

31Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism, 127.

32Matteo Grilli, Nkrumaism and African Nationalism: Ghana’s Pan-African Foreign Policy in the Age of Decolonization (Cham : Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 15-16.

33Vincent Bakpetu Thompson, Africa and Unity: The Evolution of Pan-Africanism, 130.

34Lagoke, Gnaka, Le Panafricanisme d’Hier à Demain et la Philosophie Ubuntu (Paris: Editions de l’Onde, 2025), 129-130.

35Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 31.

36Philippe Decraene, “L’Afrique noire tout entière fait écho aux thèmes panafricains exaltés à Accra”, https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/1959/02/DECRAENE/22920

37Kwame Nkrumah, Handbook of Revolutionary Warfare, 30-31.