– In a world where only 8 individuals – all of them men—possess as much as half of all the planet’s wealth, and it will take women 170 years to be paid as men are, inequality appears to be a key feature of the current economic model. Now a new study reveals that there is also a widening gap in hunger.

In fact, the 2017 Global Hunger Index (GHI) states that despite years of progress, food security is still under threat. And that conflict and climate change are hitting the poorest people the hardest and effectively pitching parts of the world into “perpetual crisis.”

Although it has been said that “hunger does not discriminate,” it does, says the 2017 Global Hunger Index, jointly published by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Concern Worldwide, and Welthungerhilfe.

According to this study, hunger emerges the strongest and most persistently among populations that are already vulnerable and disadvantaged.

Hunger and inequality are inextricably linked, it warns. By committing to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the international community promised to eradicate hunger and reduce inequality by 2030.

“Yet the world is still not on track to reach this target. Inequality takes many forms, and understanding how it leads to or exacerbates hunger is not always straightforward.”

Women and Girls

The GHI provides some examples–women and girls comprise 60 per cent of the world’s hungry, often the result of deeply rooted social structures that deny women access to education, healthcare, and resources.

Likewise, ethnic minorities are often victims of discrimination and experience greater levels of poverty and hunger, it says, adding that most closely tied to hunger, perhaps, is poverty, the clearest manifestation of societal inequality.

Three-quarters of the world’s poor live in rural areas, where hunger is typically higher.

The 2017 Global Hunger Index tracks the state of hunger worldwide, spotlighting those places where action to address hunger is most urgently needed.

This year’s Index shows mixed results: despite a decline in hunger over the long term, the global level remains high, with great differences not only among countries but also within countries.

For example, at a national level, Central African Republic (CAR) has extremely alarming levels of hunger and is ranked highest of all countries with GHI scores in the report.

While CAR made no progress in reducing hunger over the past 17 years—its GHI score from 2000 is the same as in 2017—14 other countries reduced their GHI scores by more than 50 per cent over the same period.

Meanwhile, at the sub-national level, inequalities of hunger are often obscured by national averages. In northeast Nigeria, 4.5 million people are experiencing or are at risk of famine while the rest of the country is relatively food secure, according to the 2017 Index.

This year’s report also highlights trends related to child stunting in selected countries including Afghanistan, where rates vary dramatically — from 24.3 per cent of children in some parts of the country to 70.8 per cent in others.

While the world has committed to reaching Zero Hunger by 2030, the fact that over 20 million people are currently at risk of famine shows how far we are from realising this vision, warns the report.

“As we fight the scourge of hunger across the globe, we must understand how inequality contributes to it. To ensure that those who are affected by inequality can demand change from national governments and international organisations and hold them to account, we must understand and redress power imbalances.”

The study notes that on 20 February, the world awoke to a headline that should have never come about: famine had been declared in parts of South Sudan, the first to be announced anywhere in the world in six years. “This formal famine declaration meant that people were already dying of hunger.”

This was on top of imminent famine warnings in northern Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen, putting a total of 20 million people at risk of starvation, it adds.

“Meanwhile, Venezuela’s political turmoil created massive food shortages in both the city and countryside, leaving millions without enough to eat in a region that, overall, has low levels of hunger. As the crisis there escalated and food prices soared, the poor were the first to suffer.”

This year’s report also highlights trends related to child stunting in selected countries including Afghanistan, where rates vary dramatically — from 24.3 per cent of children in some parts of the country to 70.8 per cent in others.

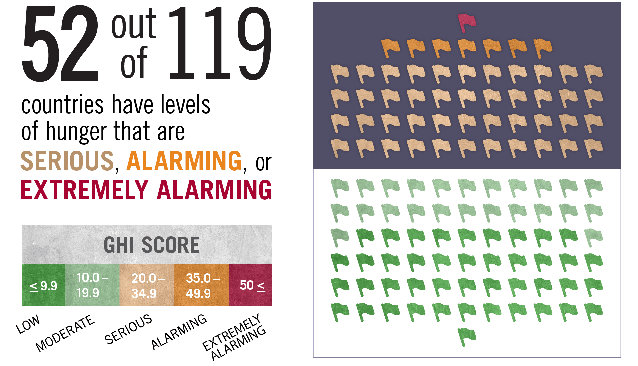

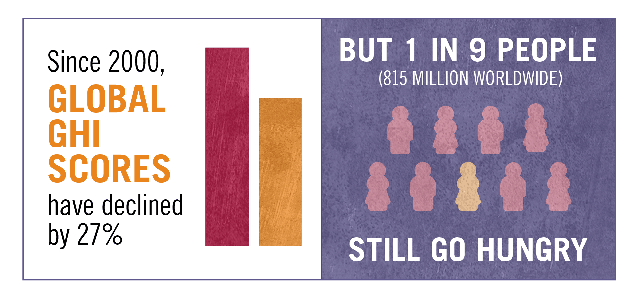

According to 2017 GHI scores, the level of hunger in the world has decreased by 27 per cent from the 2000 level. Of the 119 countries assessed in this year’s report, one falls in the extremely alarming range on the GHI Severity Scale; 7 fall in the alarming range; 44 in the serious range; and 24 in the moderate range. Only 43 countries have scores in the low range.

In addition, 9 of the 13 countries that lack sufficient data for calculating 2017 GHI scores still raise significant concerns, including Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria.

To capture the multidimensional nature of hunger, GHI scores are based on four component indicators—undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting, and child mortality.

The 27 per cent improvement noted above reflects progress in each of these indicators according to the latest data from 2012–2016 for countries in the GHI:

• The share of the overall population that is undernourished is 13.0 per cent, down from 18.2 per cent in 2000.

• 27.8 per cent of children under five are stunted, down from 37.7 per cent in 2000.

• 9.5 per cent of children under five are wasted, down from 9.9 per cent in 2000.

• The under-five mortality rate is 4.7 per cent, down from 8.2 per cent in 2000.

By Regions

The regions of the world struggling most with hunger are South Asia and Africa south of the Sahara, with scores in the serious range (30.9 and 29.4, respectively), says the report.

Meanwhile, the scores of East and Southeast Asia, the Near East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States range from low to moderate (between 7.8 and 12.8).

These averages conceal some troubling results within each region, it says, adding that however, including scores in the serious range for Tajikistan, Guatemala, Haiti, and Iraq and in the alarming range for Yemen, as well as scores in the serious range for half of all countries in East and Southeast Asia, whose average benefits from China’s low score of 7.5.

For its part, the UN State of Food and Agriculture 2017 report, released on 9 October, warns that efforts to eradicate hunger and poverty by 2030 could be thwarted by a thorny combination of low productivity in developing world subsistence agriculture, limited scope for industrialisation, and rapid population growth.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report also argues that rural areas need not be a poverty trap.

In short, hunger also discriminates against the ultimate victims of all inequalities–the most vulnerable.

Baher Kamal is Senior Advisor to IPS Director General on Africa & the Middle East. He is an Egyptian-born, Spanish-national, secular journalist, with over 43 years of experience. Since the late 70s, he specialised in all development related issues, as well as international politics. He also worked as Senior Information Expert for the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership at the European Commission in Brussels, and as the first-ever Information Officer and Spokesperson at UNEP’s Mediterranean Action Plan in Athens. Kamal speaks Spanish, Arabic, English and Italian.