– At the entrance, the Tierra Brava farm looks like any other family farm in the rural municipality of Los Palacios, in the westernmost province of Cuba. But as you drive in, you see that the traditional furrows are not there, and that freshly cut grass covers the soil.

“For more than five years we’ve been practicing conservation agriculture (CA),” Onay Martínez, who works 22 hectares of state-owned land, told IPS.

He was referring to a specific kind of agroecology which, besides not using chemicals, diversifies species on farms and preserves the soil using plant coverage and no plowing.

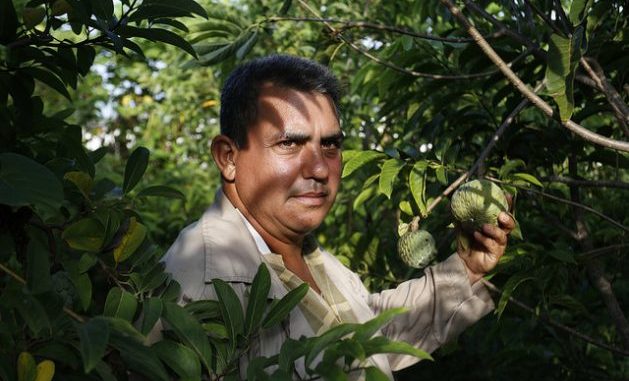

“In Cuba, this system is hardly practiced,” lamented the farmer, who is cited as an example by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of integral and spontaneous application of CA, which Cuban authorities began to include in their policies in 2016.

This fruit tree orchard in the province of Pinar del Río, worked by four farmhands, is the only example of CA reported at the moment, and symbolises the step that Cuba’s well-developed agroecological movement is ready to take towards this sustainable system of farming. The Agriculture Ministry already has a programme to extend it on a large scale.

FAO defines CA as “an approach to managing agro-ecosystems for improved and sustained productivity, increased profits and food security while preserving and enhancing the resource base and the environment. CA is characterised by three linked principles, namely: Continuous minimum mechanical soil disturbance; Permanent organic soil cover; Diversification of crop species grown in sequences and/or associations.”

Because of the small number of farms using the technique, there are no estimates yet of the amount of land in Cuba that use the basic technique of no-till farming, which is currently expanding in the Americas and other parts of the world.

CA, which uses small machinery such as no-till planters, has spread over 180 million hectares worldwide. Latin America accounts for 45 per cent of the total, the United States and Canada 42 per cent, Australia 10 per cent, and countries in Europe, Africa and Asia 3.6 per cent.

The world leaders in the adoption of this conservationist system are South America: Brazil, where it is used on 50 per cent of farmland, and Argentina and Paraguay, with 60 per cent each.

And Argentina and Brazil, the two agro-exporter powers in the region, are aiming to extend it to 85 per cent of cultivated lands in less than a decade.

“In conservation agriculture we found the basis for development because it allowed us to achieve goals in adverse conditions,” said Martínez, a computer specialist who discovered CA when in 2009 he and his brother started to study how to reactivate lands that had been idle for 25 years and were covered by weeds.

A worker operates a kind of mower characteristic of this type of agriculture to clear the paths in Tierra Brava, which has no electricity or irrigation system. The cut grass is thrown in the same direction to facilitate the creation of organic compost.

“There are places on the farm, such as the plantation of soursop (Annona muricata), where you walk and you feel a soft step in the ground,” Martínez said, citing an example of the recovery of the land achieved thanks to the fact that “no tilling is used and the soil coverage is not removed.”

Focused on the production of expensive and scarce fruit in Cuba, the farm in 2016 produced 87 tons, mainly of mangos, avocados and guavas, in addition to 2.7 tons of sheep meat and 600 kilos of rabbit.

Now they are building a dam to practice aquaculture and are starting to sell soursop, a fruit nearly missing in local markets.

Mandarin orange, canistel (Pouteria campechiana), coconut, tamarind, cashew, West Indian cherry (Malpighia emarginata), mamey apple (Mammea americana), plum, cherry, sugar apple (Annona squamosa), cherimoya (Annona cherimola) and papaya are some of the other fruit trees growing on the family farm, until now for self-consumption, diversification or small-scale, experimental production.

“Rotating crops is hard and requires a lot of training and precision, but CA is also special because it allows you time to be with your family,” said Martínez, referring to another of the benefits also mentioned by specialists.

FAO’s representative in Cuba, German agronomist Theodor Friedrich, is one of the staunch advocates of CA around the world, based on years of research.

“Agroecology, as it was understood in Cuba in the past, has excluded the aspect of healthy soil and its biodiversity,” he told IPS in an interview. “Now the government recognises that the move towards Conservation Agriculture fills in the gaps of the past, in order to achieve true agroecology.”

Friedrich said that in this Caribbean island nation of 11.2 million people, CA is new, but “several pilot projects have been carried out, and there is evidence that it works.”

In October 2016, Cuba laid out a roadmap to implement CA around the country, after an international consultation supported by FAO. And in July a special group was set up within the Agriculture Ministry to promote CA.

“CA has not been immediately adopted on a large-scale around the country,” said Friedrich. “But as of 2018, the growth of the area under CA is expected to be much faster than in countries where this system only spreads among farmers, without the coordinated support of related policies.”

Good practices that improve the soil, which form the basis of this system, have been promoted in Cuba for some time now by bodies such as the Soil Institute (IS). It is even among the few environmental services supported by the state in Cuba’s stagnant economy, to combat the low fertility of the land.

According to data from the IS, only 28 per cent of Cuban soils are highly productive for agriculture. Of the rest, 50 per cent is ranked in category four of productivity, one of the lowest, due to the characteristics of the formation of the Cuban archipelago and the poor management of soil during centuries of monoculture of sugarcane.

“In this municipality, the number of farms that use organic compost to improve the soils has increased. The payment for improving the soil has been an incentive,” said Lázara Pita, coordinator of the agroecological movement in the National Association of Small Farmers of Los Palacios.

“We have rice fields, where agroecology is not used, but where they do apply good practices for soil conservation such as using rice husks as nutrients,” Pita, whose association has 2,147 small farms joined together in 15 cooperatives, an agroindustrial state company and rice processing plant, told IPS.

Standing in a wide-roofed place without walls in Tierra Brava, Pita estimated that 40 farms qualify as ecological, and another 60 could shift to clean production techniques.

With the certification of a soil expert, a farmer like Martínez can earn between 120 and 240 dollars a year for offering environmental services, such as soil improvers, the use of live barriers and organic materials. This is an attractive sum, given the average state salary of 29 dollars a month.

Cuba, which depends on millions of dollars in food imports, has 6,226,700 hectares of arable land, of which 2,733,500 are cultivated and 883,900 remain idle.