On a book tour last month, Lampert presented some of the stories and reflections from A People’s Art History of the United States at Wooden Shoe Books in Philadelphia to a packed house eager to learn more about this history from below and beyond the elite art establishment. Afterwards, we had the following conversation about the book and what lessons can be applied to movements today.

Matt Dineen: Can you start by talking about how A People’s Art History of the United States came to be? Readers will see that the book is part of the New Press’ People’s History series which was started by the late radical historian Howard Zinn. Can you tell us the story of meeting him and getting this opportunity to participate in the series?

Nicolas Lampert: Sure. In 2003 I was teaching an art history course on Art and Social Movement in Milwaukee and was relatively new to college teaching—two years in. I knew that Howard Zinn was very well revered in Madison and would speak there often due to his connection with The Progressive magazine. So I checked online to see if he had any upcoming speaking dates and lo-and-behold he was scheduled for a mid-October talk for the Wisconsin Book Fair. I figured the Book Fair would cover his travel costs and also figured that on his route home he would be flying out of Milwaukee. So, I simply wrote him a letter and asked him if he would be willing to come to MIAD—a small art college that I taught at before moving to UWM—and talk to my class on the day that he was flying back to the East Coast for a relatively modest speaking fee. Professor Zinn emailed me back and said he would be glad to—the only catch was that I needed to pick him up on the day of the talk and drive him from Madison to Milwaukee.

So, a colleague and I met him early in the morning and had what could be described only as an incredible two-hour drive. I had expected to hear all about his interests and his life, but he instead wanted to know more about us: our interests and the movements taking place in Wisconsin. Much of the conversation was about radical art. He noted his wife was an artist and he had a great respect for artists when they turned their attention towards politics.

Towards the midpoint of the drive, my colleague and I must have made a positive impression on him because he put forth the question, “Do you like to write?” I asked why and he said that he was the series editor of “The People’s History” through The New Press. He explained the concept of the series and invited us to send him a one-page proposal that he promised to forward to an editor at The New Press if he liked it. So in one day I got to meet Professor Zinn, I got to introduce him to my students (who were studying his book), and I received an invitation that led to a new book project that would consume the next eight years of my life. The book simply would not have happened had I not met him and had he not afforded me the opportunity. It was a life lesson: a lesson to reach out to those you admire, and a lesson for me to do the same: create opportunities for others and expand the hive so that the movement becomes larger.

MD: That’s pretty amazing. What about the process of writing the book? During the years that you were researching and writing, how did you balance your own voice and political vision with Zinn’s legacy and approach to history?

MD: That’s pretty amazing. What about the process of writing the book? During the years that you were researching and writing, how did you balance your own voice and political vision with Zinn’s legacy and approach to history?

NL: Every author should and does approach things differently so my voice and vision was expressed throughout. That said, I was conscience on what “A People’s History” meant and how it should frame my study. My book—like Zinn’s study—obviously looks at history from the bottom up. I wrote about how art was utilized in social justice movements and I looked outside of the museum and the gallery for my examples. I decided that I should move through history chronologically and started essentially where Zinn did in his A People’s History of the United States with the first chapter addressing the early contact between Native and non-Native peoples. I also wanted to be sure that the book did not move too quickly into the 20th Century, so the first third of the book focuses on examples from the 17th, 18th, and 19th Century.

I also was aware of my potential audience. I did not want to write a book that only people with PhD’s in art history would understand or appreciate. It was important for me that the book could be useful to anyone from high school on up, regardless if they had studied art or art history before. This was modeled after Zinn’s approach. I wanted to bring new people into the conversation/movement.

My book differs from Zinn’s in so far that it both celebrates and critiques movements. A number of the chapters highlight examples where the tactics employed by artists fell short. These are less “celebratory” but they are instructive learning examples that can be applied to the tactics of today. My book also is not a survey. It is twenty-nine specific examples. For instance, I chose one example on the IWW (the Paterson Pageant in 1913), instead of a fifteen-page chapter that highlighted five-to-ten different examples of how the IWW employed art and culture between 1905 and the start of WWI. This approach allowed me the page count to really explore the history/art history of the example, and allowed me the space to debate what worked and what did not. It also allowed me the space to insert my voice, so in essence the book is a collection of critical essays that moves through history and showcases different mediums and tactics. The downside of that approach is that I had to make tough choices on what to include and what not to include in the study.

MD: Can you say more about tactics and what some of the examples that you chose to highlight in your book can offer for contemporary artists and social movements?

NL: In many ways the book is really a study of activist art tactics and each chapter can be instructive for today’s activists. The UK and US abolitionist movement simply instructs us about international solidarity campaigns. Shared graphics and tactics traveled across the Atlantic, as did abolitionists. Towards the end of Thomas Clarkson’s life—after sixty years of organizing against slavery and England’s primary involvement in the slave trade—Clarkson told his two invited guests, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, that if he “had sixty more they should all be given to the same cause.” The purpose of that meeting went beyond friendship and mutual respect. It was to share and debate tactics.

The suffrage movement—specifically the National Woman’s Party—utilized banners and civil disobedience throughout Woodrow Wilson’s tenure as president. For us today, we can critique the power of slogans, agitating those in power directly, and using civil disobedience to escalate a campaign, and to gain media coverage. From W.E.B. Du Bois we can debate how brutal images impact the public consciousness. During his twenty-four year run as the editor of the NAACP publication The Crisis he continuously published the most horrific images of lynching. Some might shy away from publicizing the brutal images of today because they are so painful to look at. But for others, these types of images inspire people to act. One simply has to recall the Emmett Till image and the open casket funeral in Chicago that was attended by thousands, if not tens-of-thousands of people, propelling many to commit all their energies to the Civil Rights movement and a life dedicated to activism.

Closer to the present, artists and activist groups can learn an immense amount from ACT UP who were almost second-to-none in employing art and creative resistance in their tactics during the 1980s and early 90s. What we should study is not just the images, but how the group was structured. Various cells or affinity groups existed within the NYC ACT UP branch that gave artists the independence and the creative license they needed. Artists were part of the larger structure of the group, but they also had the independence to do their work without the distraction of their images being critiqued by the entire group—which would have been impractical considering that it had 500-plus members. Moreover, a slow process would not have allowed the artists to respond immediately to flashpoints, something that artists excel at.

If we look to today, many activist groups simply ask a lone artist to make a flyer, a poster, or a banner. Artists are expected to lend their talents—often for free—and then to go away. ACT UP differed. Artists had a say in the tactics and the decision-making process of the movement. ACT UP artists—and I am primarily speaking about the design collective Gran Fury—were not paid, but their voices were respected and the structure of affinity groups was perfect for allowing artists to thrive.

MD: Finally, in your presentation in Philadelphia you concluded by highlighting some examples of particular activists and artists today including the work of fellow Justseeds collective member Favianna Rodriguez. In what ways do you see Justseeds contributing to this trajectory laid out in A People’s Art History of the United States? And how has writing the book impacted your own relationship to art and political struggle?

NL: Well it is never easy to summarize Justseeds or pin down exactly what we are. The group consists of twenty-five artists who live across North America. Some in the group—including myself—identify as activist-artists. Others might not. Significantly, Justseeds never speaks as one voice. It is a collection of individuals. What unifies us is that we are all printmakers and we all help run a workers-run print cooperative.

That said we do work on a number of group projects each year—specifically portfolio projects—that allows us to directly contribute to a movement. These portfolios become advocacy tools for a movement to use in their outreach. We typically create 125 copies of a portfolio that equates to 125 exhibitions that can be mounted around the country and the world. We also make a companion website that houses all the graphics as copy-right free pdf graphics that anyone can download and use.

To date we have created portfolio projects for the ten-year anniversary conference for Critical Resistance that addressed prison-justice issues. We created a portfolio project on resource extractions (environmental issues) whereby some of the artists—including myself—collaborated directly with a local campaign. We also created a portfolio in collaboration with Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) that addressed PTSD, military sexual assault, and traumatic brain injury. And more recently we designed a portfolio about migrant rights and the upsurge of deportations during the Obama Administration. Lastly, some in the collective contributed to a portfolio that addressed the twentieth anniversary of the Zapatista uprising.

To me, the IVAW work really stands out because of the long-term relationship that Justseeds has had with this group stemming from our friendship with IVAW organizer and artist Aaron Hughes. The process has been truly collaborative. Aaron often informs us about what types of graphics would be best suited for various IVAW campaigns and then we begin designing. Over the past five years we have created a host of collaborative projects, including a Justseeds-IVAW street art action in Chicago, a Printed Matter IVAW booklet, a portfolio called War is Trauma, and a current project that celebrates IVAW’s ten-year history.

To answer the second part of your question, writing the People’s Art History of the United States book has directly informed my own art practice. It became an education on how to collaborate as an artist in various movements. I took lessons and inspiration from many of the artists I researched from Gran Fury to Danny Lyon to the Workers Film and Photo League (F&PL) to countless others.

To answer the second part of your question, writing the People’s Art History of the United States book has directly informed my own art practice. It became an education on how to collaborate as an artist in various movements. I took lessons and inspiration from many of the artists I researched from Gran Fury to Danny Lyon to the Workers Film and Photo League (F&PL) to countless others.

I think for many of us in Justseeds, researching past radical artists and histories has become an essential part of our practice. So much so that three Justseeds members—Josh MacPhee, Molly Fair, and Kevin Caplicki—help run the Interference Archive in Brooklyn that is dedicated to the study and preservation of movement culture. I often hear Justseeds member mention how much they have been influenced by the Taller de Gráfica Popular, Elizabeth Catlett, Carlos Cortez, Malaquias Montoya, Rupert Garcia, and Lynd Ward; others were inspired by the World War 3 artists and the DIY movement associated with underground music.

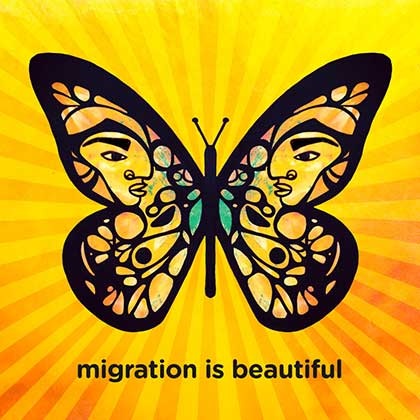

Many of us borrow generously from past movements. Favianna Rodriguez is arguably best known for her image of a butterfly with the text “Migration is Beautiful.” This graphic is a direct effort to counter how migrant workers crossing the border have been negatively portrayed in the mass media. I recall Favi explaining in a talk that she gave in Milwaukee that she drew inspiration from the ACT UP movement and how they reframed the national debate on how people with HIV were being portrayed in the media. Thus one can see a direct linkage between Gran Fury’s image “All People with AIDS Are Innocent” and Favi’s image “Migration is Beautiful.” This is the power of studying past movements. It provides us with ideas and inspirations. It is a history of tactics to borrow and adapt to the present, a toolbox to help us shape the present.

* * *

For more information about the book and Nicolas Lampert’s other projects visit: http://peoplesarthistoryus.org/

Matt Dineen is a writer and activist based in Philadelphia where he staffs at the Wooden Shoe, an anarchist bookstore. He is also a graduate student at Goddard College.