The French system’s slogan is, “Everyone contributes according to his resources and receives according to his needs.” And this is not just rhetoric. Ever since the 1940s, France has made budgetary decisions to turn this dream into reality. But in France, as in many other countries, the logic of the market is now slicing away at universal access. As has been proven elsewhere, and as some in French civil society are now realizing, a strong health care system can only survive if the population fights to protect it.

Julie Castro |Paris, France

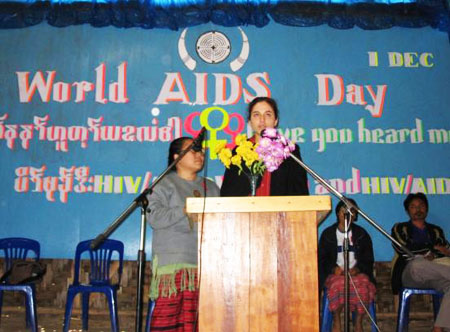

My interest in health emerged as a way to take action in the fight for social justice. During my medical studies, I did internships in Africa and India and worked in a refugee camp along the Thai-Burmese border. At the same time, I became more aware of the anti-globalization movement. It appeared to me that it was addressing the structural causes of ill health: inequality at both the global and local levels. Today, while I’m working on the fight against AIDS in Mali, I’m also one of those defending the idea that access to public health in France is a right.

Even with its problems, the French health system is a good one. It’s a distributive system. Universal access to health care is one basic value.

Our system offers equity, not making any distinction according to class, race, or gender. It could be summarized as ‘one system for all.’ In theory, poor people don’t have to pay when they go see a doctor. Today, if you arrive in a bad state in a public hospital in France, you’d be cured – wherever you come from, documented or undocumented, whatever your language, all in the same way a government minister would.

Another practical advantage, I think, is the quality of care. Even if the infrastructure is overwhelmed and lacks people, the quality of public health care is still good. In France, the best doctors and best care are to be found in the public hospitals and in the university teaching hospitals.

But the system is under great threat now. A sentence you can hear everywhere is, “There’s a hole in social security” [the fund which pays for health care, retirement, and other social benefits]. We’re told, “Okay, the health system is too costly, money is lacking, we have to spend less.” Now in the hospitals, doctors are told not to prescribe too much of this or that, and all health workers are even trained not to use too much gauze – because it’s all reimbursed by social security.

Talking about a hole is a flawed statement. Long-term benefits – like lives saved, illnesses prevented, and years of work spared – aren’t included in this consideration. It’s an ideological stance, a question of where we decide to put our money.

We already see how this is playing out in the US. American medicine has a reputation that you can be dying in front of a health facility, and they’ll ask you, “Do you have insurance?” And, if you don’t, you just die. This is very shocking to many French people. The other thing that we observe from this side of the ocean is the stigmatization of very poor people.

Cutting the budget so we move toward a US model is only one answer to “filling in the hole.” The direction we should be taking is to improve prevention and start to truly tackle the social determinants of health [the conditions in which people are born, live, and work, which are determined by social factors such as income levels and power]. This implies, of course, substantive shifts in many policy sectors: housing, labor market, education.

Translated by David Dudar.

Inspired? Here are a few suggestions for getting involved!

- Demand that government-funded research of pharmaceuticals be available to all medical researchers and not simply given to private corporations for profit-making. Fight for the availability of affordable medicines around the world. Medecins Sans Frontieres has a campaign for the access to essential medicines (www.msfaccess.org).

- Organize to change state health care legislation. Visit the Universal Health Care Action Network’s State Connections map to find out what groups organize around health care justice in your state (www.uhcan.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=section&layout=blog&id=7…).

- Join the Healthcare-NOW campaign to pass HR 676. It would establish an American national universal health insurance program by creating a publicly financed, privately delivered health care system that uses the already existing Medicare program (www.healthcare-now.org/campaigns/win-win).

- Get involved with the movement for a single-payer national health insurance system. Health professionals can link up with Physicians for a National Health Program by becoming a member, and everyone can check out their suggestions for action (www.pnhp.org/action/activism).

And check out the following resources and organizations:

- Women of Color United, End Violence Against Women and HIV & AIDS, www.womenofcolorunited.org

- SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective, www.sistersong.net

- Hesperian Foundation, www.hesperian.org

- Health Care Without Harm, www.noharm.org

- “People’s Charter for Health,” People’s Health Movement, www.phmovement.org/en/resources/charters/peopleshealth

- “Access to Medical Technology,” Knowledge Information Technology, www.keionline.org/a2m

- “Resources and Videos,” Healthcare-NOW, www.healthcare-now.org/takeaction/books-and-videos

- Meredith Fort et al., eds., Sickness and Wealth (South End Press, 2004)

- Jim Yong Kim et al., eds., Dying for Growth: Global Inequality and the Health of the Poor (Common Courage Press, 2000)

- Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor (University of California Press, 2005)

- “Sicko,” directed by Michael Moore, Dog Eat Dog Films, 2007

- “Sick Around the World,” directed by Jon Palfreman, PBS FRONTLINE, 2008, available online at: www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/sickaroundtheworld

- “Critical Condition,” directed by Roger Weisberg, PBS/POV, 2008, available online at: www.pbs.org/pov/criticalcondition/

- “Health, Money and Fear,” directed by Dr. Paul Hochfeld, available online at: www.ourailinghealthcare.com