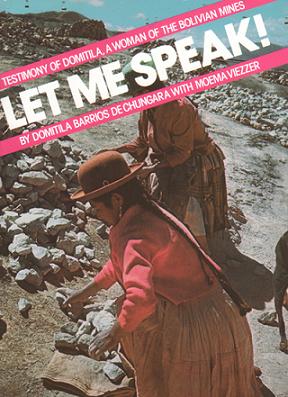

Reviewed: Let Me Speak!: Testimony of Domitila, A Woman of the Bolivian Mines, By Domitila Barrios de Chungara, (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1978).

The life experiences of Bolivian mining activist Domitila Barrios de Chungara traverse some of the most important and tumultuous events in 20th century Bolivian history. Her account of this life in the book Let Me Speak! offers a view from the trenches of militant, leftist organizing within the country labor movements and beyond.

Chungara’s account provides insight into the National Revolution of 1952, the failed guerrilla insurgency in Bolivia led by Che Guevara, the country’s brutal experience in the Cold War, and the frequent coups, dictatorial crackdowns and popular uprisings that marked the Andean country’s rocky century.

Let Me Speak! begins with Chungara’s descriptions of the labor she and her fellow workers go through. This work is excruciatingly difficult, and involves little sleep, poor income and a lack of sufficient food, housing and services. As a woman, Chungara’s labor does not end with her work in and around the mines; she has to take care of her children, help them complete their school work, prepare food for the family and conduct an endless round of tasks both day and night to keep the family alive and able to work and attend school.

In a typical example of Chungara’s analysis of this labor, she said, “I think that all of this proves how the miner is doubly exploited, no? Because, with such a small wage, the woman has to do much more in the home. And really that’s unpaid work that we’re doing for the boss, isn’t it?” She explained, however, that by participating in the union as a woman she gained power over her work and freedom through advocating for women’s rights both in the workplace and at home.

This story of everyday struggle gives way to yet even more dramatic conflicts as a leading labor organizer both in her own mining community, and on a national level. This work comes at a cost however, as the mine owners and government officials are constantly trying to harass, beat and intimidate Chungara into submission. At one point she is jailed and tortured, but eventually escapes. At other points she is a witness to bloody massacres of miners, and brutal government repression of strikes and labor meetings.

This story of everyday struggle gives way to yet even more dramatic conflicts as a leading labor organizer both in her own mining community, and on a national level. This work comes at a cost however, as the mine owners and government officials are constantly trying to harass, beat and intimidate Chungara into submission. At one point she is jailed and tortured, but eventually escapes. At other points she is a witness to bloody massacres of miners, and brutal government repression of strikes and labor meetings.

Chungara’s account describes the ideology that underpins the potency of the mining sector in Bolivia at this time. Her recurring references to the importance of solidarity between comrades, analysis of US imperialism in its crackdown on communism and leftists in general, and her conviction that she is struggling for a better future for her children, are traits she apparently shares with her fellow activists, workers and mothers.

Her interactions with manifestations of US political power and culture are also illuminating. In one case she describes how the Hugo Banzer dictatorship decided to crackdown on the labor organizing and consciousness that was empowered by the miners’ community radio by giving away free TVs to mining communities, while at the same time destroying the radio’s transmitters. According to Chungara, who refused the free TVs, the TVs replaced informative radio announcements tied to the miners’ everyday life and political formation with Disney cartoons and films from Hollywood. Chungara said this change provoked more greed and individualism and a breakdown in relationships between people of different generations. During another of her interrogations, Chungara also speaks with US officials in the office of the Alliance for Progress, an interesting exchange at a time of heightened tensions between the US government and communist sympathizers.

At one point in her story, the Banzer dictatorship sent government officials to Chungara’s mining community to try and end a strike. One of the officials argued against the striking miners by explaining that the country’s economic problems were due to the miners’ leftist ideology and recurring strikes. The official threw around a bunch of numbers to illustrate his point. Chungara’s response underlines the importance and power of her testimony’s perspective. “We don’t live off of numbers. We live from reality.”

Benjamin Dangl is the author of books Dancing with Dynamite: Social Movements and States in Latin America and The Price of Fire: Resource Wars and Social Movements in Bolivia (AK Press). He edits TowardFreedom.com, a progressive perspective on world events, and UpsideDownWorld.org, a website on activism and politics in Latin America. Email Bendangl(at)gmail(dot)com.