A Toward Freedom Special Report

By Charles Wachira

Three months after Yoweri Museveni was re-elected president of Uganda for a sixth term, citizens of this strategic East African state are trying to come to terms with the dismal likelihood that he will never be unseated in free and fair elections. Ever since 1986, when he came to power in the country’s first plural elections, this African strongman has enjoyed the continued and tacit support of successive US administrations. The fact that Uganda discovered oil in 2006 has also enhanced his value as a close ally to the West in a turbulent neighborhood. Today, Uganda is described as having the fourth largest onshore oil reserves in sub-Sahara Africa.

Museveni’s victory on January 14th was not, however, a foregone conclusion; his international backers had to take notice that a significant threat came from the nation’s large youthful population. A 39-year- old pop musician-turned-populist politician named Bobby Wine became a close contender for the country’s top seat, momentarily rattling the confidence of a junta safely ensconced in Kampala. Wine had “street credentials” and appealed to the country’s large youth population, to the point that he was considered close to being a shoe-in.

According to the World Bank, more than 75% of Uganda’s population is below the age of 30, with the country having one of the highest youth unemployment rates– at 13.3%——in Sub-Saharan Africa. This means that 75 % of Uganda’s population has known no other leader save for Museveni, who has ruled Africa’s largest coffee exporter –and now an oil producer– for an uninterrupted 35 years and counting.

The relatively youthful Wine was widely thought to be drawing support from this demographic.

Back in 2018, the Financial Times was already warning of his appeal: “Across the continent, Mr. Wine’s spreading fame has put leaders on notice that they face a youthful rebellion.” Africa has the youngest population in the world, with a median age of 19.5. Uganda’s is just 16. But the continent has the world’s oldest leaders, with an average age of 62. Incumbents are clinging on, well past their sell-by date.”

During the run-up to the elections, Wine (whose real name is Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu) resorted to wearing a helmet and a bulletproof vest to campaign in what he once described as a “war zone.” In November, 2020, he was arrested, beaten and barred from campaigning by the state’s security apparatus. When protests broke out after Wine’s arrest, security personnel resorted to using live bullets, killing more than 50 people.

Once hailed as Uganda’s savior, Museveni’s political stock leading up to the recent election was in free-fall. A poll conducted by Research World International Ltd, , a Ugandan social research agency, showed his popularity at 32 per cent, his lowest ever in his 35-year reign.

According to the Uganda Electoral Commission (UEC), the body that runs the electoral process in the country, Museveni won 58.6% of the vote while Wine managed 34.8%. Yet the turnout was only 52% of registered voters, the lowest since Museveni took office in 1986.

Even the top US diplomat for Africa, Tibor Nagy, felt compelled to tweet on January 16th that “Uganda’s electoral process has been fundamentally flawed.”

Wine contested the outcome, claiming “vote rigging” and seeking recourse in the Supreme Court before withdrawing the challenge on February 22, charging that Uganda’s courts were filled with “yes-men” appointed by Museveni.

Museveni’s Value to the West

When Museveni rode to power in 1986, he was hailed as a liberator and peacemaker following years of tyranny under Idi Amin (1971-1979) and Milton Obote (1966 to 1971; 1980 to 1985.) His regime has been credited with reforming the East African country’s economy, which, after the ravages of Idi Amin and Milton Obote, was on the verge of collapse when he took over, with inflation at more than 200%.

The World Bank continued to give him high points on managing the economy under its tutelage.

“Uganda’s economic performance since 1987 has been impressive,” the World Bank noted in a report titled Reducing Poverty Sustaining Growth Scaling Up Poverty. “The country has sustained economic growth averaging 6 percent and maintained an inflation rate in single digits. In just eight years (between 1992 and 2000), the proportion of people living in absolute poverty declined from 56 percent to 35 percent,”

However, Museveni’s rule has been marked by more years of harsh repression, drawing comparisons to the tyrannical, 72-year-long reign of Louis XIV in France during the Ancien Régime and the ruler’s famous diktat, “L’état, c’est moi” or “I am the state.”

Some Washington insiders are now calling for the re-evaluation of US support for the dictator. Jeffrey Smith, director of the advocacy nonprofit Vanguard Africa, told World Politics Review this January that, “There needs to be a review of U.S. policy towards Uganda, including a comprehensive review of the millions of dollars we provide on an annual basis to their security forces and military.” An appeal has gone out to previous donors to stop backing Museveni. “This oppressive regime is bankrolled by international donors,” notes Rita Abrahamsen and Gerald Bareebe of the University of Ottawa, Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in an article published this February titled: The Aid Debate: Time for Donors to Drop President Museveni.

“Museveni has succeeded in establishing Uganda as a key ally of the US and a pivotal state in the fight against terrorism,” the authors add. “The country has been a top troop contributor to the African Union’s peacekeeping mission in Somalia, and its soldiers have also been deployed to other trouble spots like South Sudan and the Central African Republic.”

In return, “Uganda has been lavished with development and military assistance. As the main donor, the United States supports Uganda with nearly $1 billion a year, while another billion flows from other countries and institutions like the World Bank.”

Besides the US and the World Bank, the authors indicate that Canada has also been bankrolling the Museveni Administration.

Yet these critics appear to be in the minority. His usefulness as a regional policeman predominates.

According to Foreign Policy, an influential American news publication that focuses on global affairs, the US has trained more troops from Uganda than from any other country in sub-Saharan Africa except Burundi.

The U.S. State Department’s website also emphasizes Uganda’s value as “a reliable partner for the United States in promoting stability in the Horn of Africa and East and Central Africa and in combatting terror, particularly through its contribution to the African Union Mission in Somalia.”

Uganda, the State Department continues, provides Somalia with “assistance of around $970 million per year—equivalent to nearly 3 percent of Uganda’s GDP. Since 2014, Washington has also donated roughly $270 million in military equipment to Uganda, including multiple armored trucks, under the African Peacekeeping Rapid Response Partnership, which supports nations involved in peacekeeping efforts.”

What’s Really at Stake? A Look at The Oil Factor

In 2006, Uganda discovered oil in the Albertine Rift Basin located in the western part of the country near its border with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) This discovery put Uganda on the global energy map, turning it into East Africa’s biggest crude oil producer.

In 2009 Sally Kornfeld a senior analyst in the US Office of Fossil Energy, said Uganda’s oil reserves could be as much as that of the Gulf countries. “You are blessed with amazing reservoirs. Your reservoirs are incredible. I am amazed by what I have seen; you might rival Saudi Arabia,” she told a visiting delegation from Uganda in Washington DC.

By 2014, the Ugandan Government estimated that there were 6.5 billion barrels of oil in place, but recoverable oil is estimated to be between 1.8 and 2.2 billion barrels.

“The oil era is dawning in Uganda,” says Ben Shepherd, a leading specialist on African politics and conflict at the London-based Royal Institute of International Affairs. An independent policy institute, the Royal Institute issued his report titled Oil in Uganda: International Lessons for Success.

Uganda, he noted, “has the potential to accelerate development and drive the country’s transformation into a regional – and even global – economic player.” But oil also had its risks, he added — that of “eroding the relationship between people and government, of economic distortion, of increased corruption, and of internal tensions.”

The country’s first oil production is expected to happen in 2023, hitting its peak at around 200,000 barrels per day by 2028, making it the fourth largest producer in sub-Saharan Africa.

Ed Hobey-Hamsher, a senior Africa analyst at the global risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, argues that oil and gas potential in the region is vast. “I don’t think anyone wants to be left behind,” he told the African Business monthly magazine, on 13 November, 2020 referring to competing foreign oil companies.

“It’s not an easy place to do business but that certainly doesn’t mean that international oil companies (IOCs) can afford to overlook it.”

To kickstart production, Uganda has partnered with Big Oil, in this case, the French giant Total and the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation.

Construction of a 1,445km (898 miles) planned crude oil pipeline, known as the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) or, alternatively, the Hoima-Tanga Port Oil Pipeline (describing its point of origin and its terminal point) is expected to run from the Albertine region in Uganda, which is landlocked, to the Tanzanian seaport of Tanga.

It will cost $ 3.55 billion and is planned to have the capacity of 216,000 barrels per day.

Thirty percent of the project costs are expected to be provided by the equity investors, which include the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC), the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC), CNOOC Limited (the largest producer of offshore crude oil and natural gas in China and one of the largest independent oil and gas exploration and production companies in the world) and Total, the world’s fourth-ranked international oil and gas company.

The US will provide loans worth $2.5 billion.

Pipeline Politics

In March 2021, following protests against the pipeline by 263 environmental and human rights organizations, Barclays and Credit Suisse became the first major international commercial banks to confirm that they would not participate in the pipeline project.

“Barclays does not intend to participate in the financing of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline project,” the UK-based bank said in its response to the protests. Credit Suisse also confirmed it “is not considering participating in the EACOP project.” The “Stop EACOP” coalition also commented that other banks such as United Overseas Bank (UOB) had also made statements indicating that they may not be involved in the project financing.

The New Yorker, an American weekly magazine, describes the East African Crude Oil Pipeline as “one of the planet’s ugliest infrastructure projects,” for it threatens to “endanger as many animals as possible, take out wide swaths of farmland, almost all of it tilled by peasant farmers and encroach on forests.”

However, work on the pipeline is proceeding. On April 10, Uganda, Tanzania. Total and CNOOC signed agreements which will allow the “start of investment in the construction of infrastructure that will produce and transport the crude oil.”

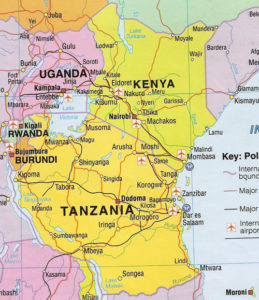

According to Mr. Murithi Mutiga, Project Director for the Horn of Africa at the International Crises Group (ICG) “Despite being landlocked, Uganda is located in a highly strategic location of the continent. It straddles across different regions,” he says.

“It’s partly in Central Africa and wholly within the East African region. It’s a member of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), an eight-country trade bloc in Africa that includes governments from the Horn of Africa, Nile Valley and the African Great Lakes.”

Uganda, Mutiga adds, “is also a member of the East Africa community (EAC) that comprises countries of Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan. To that extent, Uganda’s location makes it a major actor across the region.”

The Militarization of Uganda…and Its Neighbors

What makes Uganda’s location “highly strategic” has much to do with ongoing oil exploration throughout much of East Africa, a region which partly borders the Red Sea that separates East Africa from oil-rich Saudi Arabia. The militarization of these regions – under the pretext of fighting terrorism – often occurs in order to safeguard foreign oil concessions and pipeline routes, as explained by Charlotte Dennett in The Crash of Flight 3804: A Lost Spy, A Daughter’s Quest, and the Deadly Politics of the Great Game for Oil . As she points out, where there are terrorists, one will often find oil. Which raises the question: who is backing the terrorists in any given case? More often than not, she points out, the US and its Gulf allies have been found to be clandestinely bankrolling the terrorists.

Uganda has partnered with the US to “quell terrorism,” deploying more than 6,200 troops to the 14-year-old African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) that is battling the al Qaeda-linked group al-Shabaab, an Islamist insurgent group based in Somalia.

Dating back to the administration of Bill Clinton in the 1990s, the United States developed the Front Line States Initiative in which it formed a military partnership with Uganda which saw the latter being used as a conduit for military aid to rebels in neighboring southern Sudan (now South Sudan) battling the brutal Islamist government in Khartoum, Sudan. Seldom mentioned in the US press, however, is US competition with the Chinese in developing South Sudan’s oil.

At the time, Museveni established himself as a bulwark against militant Islam, a strategy that paid additional dividends when the US said it was concerned about the rise of al Qaeda in eastern Africa after the 1998 embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania.

Generous U.S. assistance has been additionally forthcoming following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. It was in 2007 when the African Union authorized the creation of the African Union Mission to Somalia. Since then AMISON has become an active, regional peacekeeping mission operated by the African Union with the approval of the United Nations to fight the threat of al-Shabaab. By 2012, the UK-based Guardian published an article showing the link between Somalia’s oil potential (given its proximity to East African oilfields) and military offensives to stop al-Shabaab. “Kenyan, Ethiopian and Ugandan soldiers are in Somalia,” it reported, “fighting al-Shabaab, and each country has vested interests in Somalia’s future. Already a new militia, led by the unlikely-sounding Sheik Atom, has formed around Puntland’s oilfields.”

In December, 2020 President Trump ordered the withdrawal of 700 US troops from Somalia which were training Somali forces to fight al Shabab. Trump’s order drew some rebukes within Washington. Jim Langevin, the Democratic chair of the House subcommittee on intelligence and emerging threats, equated the withdrawal as “a surrender to al-Qaida and a gift to China.”

And Benjamin Friedman, the policy director of the Defense Priorities think-tank, noted that “the change is not necessarily a step toward ending American military involvement in Somalia’s civil war.”

Benjamin Friedman, the policy director of the Defense Priorities thinktank, welcomed the move as a step in the right direction in reducing US exposure abroad.

“It seems to be a shift away from a broader effort to fight on behalf of the Somali government against al-Shabaab to a more focused counter-terrorism mission,” Friedman said.

A report published this March by the Royal Institute of International Affairs, titled “Understanding US Policy in Somalia: Current Challenges and Future Options” confirms that since 2006, Washington’s principal focus with regard to Somalia has been on reducing the threat posed by al-Shabaab.

“Successive US administrations have used military and political means to achieve this objective. Militarily, the US has provided training, equipment and funds to an African Union operation, lent bilateral support to Somalia’s neighbours, helped build elements of the reconstituted Somali National Army (SNA), and conducted military operations, most frequently in the form of airstrikes. Politically, Washington has tried to enable the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) to provide its own security, while implementing diplomatic, humanitarian and development efforts in parallel.”

Brig. Gen. Matthew Gureme, chief of staff of Uganda’s Rapid Deployment Capability Centre, told Foreign Policy on February 18, 2016 “This partnership really grew post-9/11. We were identified as one of the partners who had a common interest in combatting this terrorism,” adding “If it wasn’t for this partnership, I think the threat would be substantial enough that we would even feel it here at home.”

The Ugandan military has been embroiled in conflicts in neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and South Sudan. In the DRC, the Ugandans were accused of looting the country’s natural resources, while in South Sudan they fought on behalf of President Salva Kiir in the country’s civil war even after the United States called on them to withdraw. Also the Ugandan peacekeepers in Somalia have been accused of serious human rights violations, including sexual violence and torture.

According to Helen Epstein, an American author of Another Fine Mess: America, Uganda and the War on Terror, President Yoweri Museveni has been “… the region’s pyromaniac since he came to power, whether we are talking about Sudan, South Sudan or Rwanda or the Democratic Republic of Congo, his army has intervened everywhere, to the detriment of peace.”

Abdullahi Boru Halakhe, a security analyst who focuses on the Great Lakes and Horn of Africa regions, acknowledges that the Ugandan strongman has “put his army into the service of the global war on terror, thereby shielding himself from criticism.”

The “African Renaissance”: Uganda in a Historical/ Geopolitical Context

What has happened to Uganda is best understood by looking at the regional history of Sub-Saharan countries. In the 1980s and 1990s, these countries were disproportionately holding multiparty elections. During this period, the proxy wars of the U.S. and Soviet Union for domination of the continent, and the territorial ambitions of Apartheid South Africa had supposedly given way to a new generation of African leaders promising their western benefactors, including the US, that they would transform the continent. That dream was dubbed the African Renaissance, a contrast to the so-called “big man syndrome” – the autocratic rule by the so-called “big men” of African politics experienced during the first two decades after independence from colonialism.

For example, when former US president Bill Clinton made his initial African visit in March 1998, he helped popularize this notion of an African Renaissance, when he said he placed hope in a “new generation of African leaders” devoted to democracy and economic reforms.

Although Clinton did not pinpoint the African leaders he was referring to, it was widely assumed that he was referring to, among others, Museveni of Uganda, Paul Kagame of Rwanda, Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia and Isaias Afewerki of Eritrea. Other leaders added to the list included Ghana’s Jerry Rawlings, Mozambique’s Joaquim Chissano and South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki.

In 1998 then U.S Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said: “Africa’s best new leaders have brought a new spirit of hope and accomplishment to their countries, and that spirit is sweeping across the continent. They know the greatest authority any leader can claim is the consent of the governed. They are as diverse as the continent itself. But they share a common vision of empowerment–for all their citizens, for their nations, and for their continent.”

Yet over the years, Museveni, for one, did not live up to such lofty democratic ideals. He has deliberately suppressed opposing voices, and the elections this year were just the latest example. Only this time, on January 30, 2021, even the US State Department issued its “significant concerns about Uganda’s recent elections,” in a statement emailed to The New York Times:“The United States has made clear that we would consider a range of targeted options, including the imposition of visa restrictions, for Ugandan individuals found to be responsible for election-related violence or undermining the democratic process.”

Invariably, past condemnations of Uganda have come to be seen by Ugandan locals as loaded with levity, for nothing consequential ever emerges. An exemplar happened in 2014, when then-President Barack Obama censured the country’s draconian anti-homosexuality act, warning the Ugandan President that “enacting this legislation will complicate our valued relationship.” But a month later, Obama pledged 100 American troops to help Uganda’s hunt for Joseph Kony, commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group notorious for massacres of civilians and other atrocities.

In addition, on March 5, 2019, Museveni was accused of supporting rebels in the region – an allegation that would resurface time and time again during his long tenure. The Uganda ruler’s incursion into neighboring countries is underlined by two key factors: an avaricious appetite for economic predation and a real feeling of trepidation that an insurrection could occur seeking to upend his forbidding reign, stirred by local rebels that are itinerant within the East and Central Africa regions.

For example, the UN stated in 2001 that the DRC was suffering a “systemic and systematic” looting of natural resources by foreign armies, which included the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF).

UPDF also had close ties with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) under John Garang that witnessed UPDF invading this oil-rich state with the aim of fending off military support that the Sudan government, then a nemeses of the Administration of Garang, was providing to the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

In the late 1990s, Museveni’s moral standing took a particularly hard hit when Uganda and Rwanda invaded the Democratic Republic of Congo twice. Both armies were later charged in The Hague with looting the DRC’s resources, killing and torturing civilians and using child soldiers.

But while Museveni has continued to curry favor with the West and still receives support from financial institutions, including the World Bank, his government has used their support only to undermine the very interests his government “is lauded for safeguarding,” observed Michael Mutyaba, an independent researcher on Ugandan politics in a telephone interview with the writer, on April 1, 2021.

Here Mutyaba was alluding to Museveni’s disproportionate use of monies received from western benefactors.

In short, Museveni’s powerful benefactors have succeeded in helping him militarize the state, which in turn brutalizes its citizenry, making Uganda a police state that stands in sharp contrast to the US’s much vaunted “African Renaissance.”

Charles Wachira is a foreign correspondent based in Nairobi, Kenya and is formerly an East Africa correspondent with Bloomberg LP. He covers issues including human rights, business, politics and international relations.