Thousands of Central Americans, mostly Hondurans, fled their home countries in early October of last year to seek asylum in the U.S. Most arrived at the border in December, after completing an over 2000-mile trek across Central America and Mexico. With thousands more leaving the Honduras-Guatemala border recently, Tijuanana, Mexico city officials estimate that the number of migrants arriving in their city could reach as high as 10,000.

The first of the migrants to arrive at the U.S./Mexico border in this recent, high-profile exodus were around 80 LGBT Hondurans fleeing persecution and discrimination in their home country. The UN has received information on nearly 300 killings of Honduran LGBT individuals in the decade between 2008 and 2018, says Victor Madrigal-Borloz, the UN Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.

While murders of LGBT people in Honduras are prevalent, prosecution of hate crimes against them is rare. Of the 141 killings of LGBT people between 2010 and 2014, only 30 cases have been prosecuted according to a 2015 report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The low prosecution rate is partly due to the lack of resources for the country’s national investigative system to gather evidence and the judicial system not providing enough protection for witnesses or victims, reads the report.

According to testimony Carlos – a gay Honduran migrant – gave to Amnesty International regarding the attacks against his LGBT friends in Honduras, “as soon as a friend of mine reported the abuse, those who had committed it went to his house to get him. That’s why he ran away to Mexico. Another friend was killed right after he reported what had happened to [himself].”

Due to survivors’ fear of retaliation from accused perpetrators of violence against LGBT people, a lack of nationwide data on these crimes, and the necessity of a third person to identify the victim as a member of the LGBT community, many think that the actual number of LGBT murders is quite higher, according to Honduran LGBT activist Nelson Arambù.

Arambù was a leading LGBT activist in Honduras until his untimely death in February of 2015 due to medical complications. Gathered in front of an American audience at a Gay Liberation Network event in Chicago seven months before his passing, Arambù painted a horrifying picture of the issues facing communities in Honduras.

“A lot of people are dying, and they’re dying in atrocious ways. There are photos that have been taken in the media where you’ll see our transgender sisters mutilated, tortured, their bodies tossed about in the streets in pieces,” said Arambù. “Not too long ago, a gay comrade was pulled out of an organization, disappeared for several days and newspapers had reported he was found beaten, tortured, raped, killed with a rock against his head, and then they lit him on fire. This is something that is taking place. And that might be hard to understand in the United States because it sounds like a horror movie. And it is a horror movie.”

Arambu acknowledged that it may be difficult for the LGBT community in the U.S. to fully understand or identify with the struggle faced in Honduras. In the U.S., the struggle for LGBT rights “is in another dimension – the right for marriage, guarantees in work – but [in Honduras] we’re struggling to survive, to live, for them not to kill us, not to assassinate us,” said Arambù. “Our struggle is a basic one.”

Although prevalent, Arambù didn’t believe that these murders alone fully encompassed the issues faced by LGBT Hondurans. “We’re using homicides as the indicator of violence, but we’re not documenting the attacks, kidnappings, extortions, beatings, expulsions, firings from work, or the young students in universities kicked out of schools,” he said at the conference. “We need to respond to this crisis, they’re killing us, but evidently in a state with an authoritarian government, they silence the voices and won’t let you have much impact.”

Honduras is considered one of the most dangerous countries for human rights activists, according to the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Violence against activists has extended from the days following the 2009 military coup in Honduras with assassination of Walter Tróchez, a prominent LGBT activist, to the murder of Rene Martínez, the president of the Honduran LGBT rights organization Comunidad Gay Sampredrana, who was strangled to death in June 2016.

To fully understand the context of what led tens of thousands of migrants, including those from the LGBT community, to leave Honduras over the last decade, it is necessary to explore the U.S.-backed military coup that destabilized the nation.

The Honduras Coup, Subsequent Violence, and U.S. Complicity

In 2009, then Honduran President Manuel Zelaya had earned powerful enemies. His leftist policies had frustrated both Honduran conservative leaders as well as corporate interests as he increased the minimum wage by 60 percent, banned open-pit mining in the country, and accepted a controversial petition from feminists in the country supporting day-after contraceptive pills. From these competing interests came a political deadlock, which Zelaya sought to overcome by holding a referendum asking the public if they would support constitutional changes. His opponents framed this as an attempt to extend term limits – which he repeatedly denied it was – and in the early hours of the night on June 28, 2009, soldiers entered his home and exiled him to Costa Rica without trial.

The White House’s response was slow, but within a few days, President Obama’s public stance was clear: reinstate President Zelaya. However, at the Department of State things were not so straightforward. Rather than pushing for reinstatement, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton envisioned a different path. According to Clinton’s 2014 book Hard Choices, the State Department had no intention of restoring Zelaya, focusing instead on attempting to support a new election. This decision, combined with several Republican lawmakers with ranking position on U.S.-Latin American Policy welcoming the overthrow of Zelaya, led to inaction on behalf of the U.S. This complacency and later recognition of the new government which replaced Zelaya in turn allowed for fraudulent elections and political instability to go unchecked. Following the coup, the U.S. continued to provide crucial funding to the country, enabling the political repression against dissidents that followed.

After the coup, the Honduran government effectively stopped functioning for the people, and instead focused on suppressing the pro-democracy movement in the country. As important institutions and law enforcement ceased to maintain stability, gang violence ravaged the country, and Honduras quickly became one of the most violent countries in the world, reaching record per capita homicide rates.

State-led political violence in the region combined with discriminatory police forces and homophobic gangs that controlled entire neighborhoods in Honduras, quickly made the country an incredibly dangerous place for members of the LGBT community. In addition to the nearly 300 reported killings of LGBT individuals in the decade between 2008 and 2018, almost 90 percent of Central American LGBT asylum seekers – including those from Honduras – experienced sexual and gender-based violence, according to a 2016 study by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees.

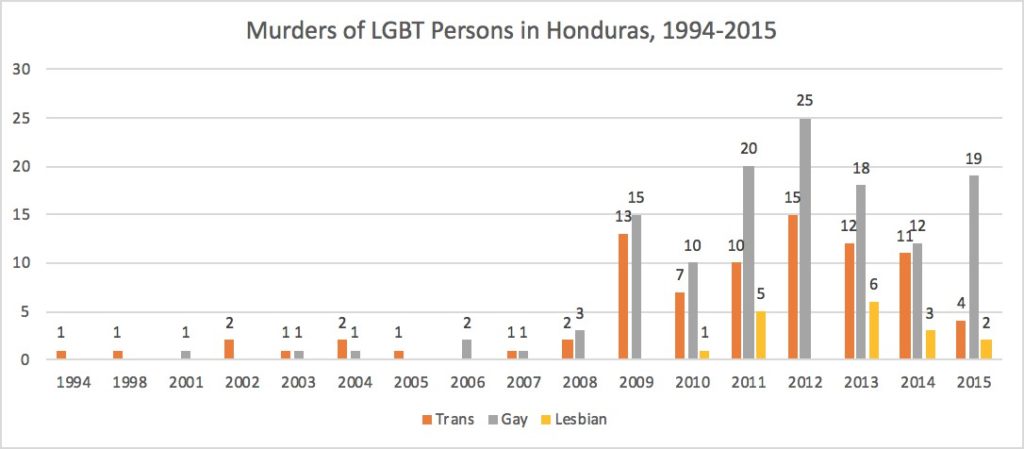

Life has not always been this dangerous for the LGBT community in Honduras. According to data compiled by Honduran LGBT advocacy and monitoring group Cattrachas, the average homicide rate for LGBT individuals was 1.4 deaths per year between 1994 and 2008. But in 2009, the number of homicides skyrocketed. As the government destabilized, extended repression against the Honduran public, and criminal gangs took control of communities, the murders jump to nearly 30 LGBT people reported killed per year.

Number of LGBT murders reported per year in Honduras between 1994 and 2015. Data obtained from Cattrachas.

There have been some measures put in place by the Honduran government to combat discrimination and violence against LGBT persons, such as appointing a special counsel and selecting a special prosecutor to deal specifically with LGBT issues, according to Madrigal-Borloz. Additionally, with Honduras’ first ever Secretary for Human Rights appointed in 2018, citizens hope this will increase protections of LGBT activists.

“Effective and meaningful social change is possible within a generation,” says Madrigal-Borloz. Many countries that criminalized homosexuality or certain forms of gender identity 25 to 30 years ago now have very progressive environments, he adds. “But the steps need to be taken immediately so that people who are facing and suffering from violence today will be protected today as well. While the measures for protection are positive steps forward, the situation for LGBT community members is far from being safe and supportive,” says Madrigal-Borloz.

Although Honduras saw a decrease in overall homicides in 2017 compared to previous years, the environment is still dangerous for the LGBT community. Murders still occur, and according to Madrigal-Borloz, hate speech against LGBT people is on the rise. “It is very much related to the populist discourse by certain politicians, but also by other sectors of public life, such as specific churches and other sectors of society,” he says. Polarizing political discourse has precipitated violence in the nation. Thirty people were killed for protesting the fraudulent results of the 2017 presidential election, according to the Committee for the Families of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras.

A Backlogged System

As thousands flee a country destabilized in the aftermath of a military coup accepted by the U.S., they arrive at the U.S. to a new government that is anything but welcoming.

Getting into the U.S. on an asylum claim is a competitive process. Since 2010, the UN has noted a steady increase in the number of people applying for asylum from Central America, with nearly 35,000 Hondurans looking for refugee status in foreign countries throughout 2017. During the same year, the U.S. accepted 208 asylum requests of Hondurans out of the 5,000-person refugee admission ceiling for all of Latin America, according to the Department of State Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. This ceiling, up from the 1,500-person cap at the end of Obama’s presidency, fell again to 1,500 in 2018 and is now at 3,000 in 2019.

Compounding the current administration’s rhetoric toward migrants fleeing to the U.S. from Central America was Jeff Sessions’ announcement on June 11, 2018, in which he stated that domestic abuse or gang violence were not grounds for asylum claims. It was over six months later that a federal judge blocked this ruling, meaning that in the interim many had already been denied asylum.

There are two ways for migrants to obtain asylum. The first is through the affirmative process within one year of the date of their last arrival in the United States or from the border. The second way is the defensive process which occurs when you request asylum as a defense against removal from the U.S., according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. After this, the migrants are put through credible fear interviews wherein an asylum officer determines if it is likely that the asylum seeker would be eligible for asylum status based on their reasons for leaving their home country. They are then provided a date in immigration court, but due to backlogs, this could be months down the road.

Already backlogged immigration courts have now experienced further postponement of hearings on thousands of immigrants entering the country due to the furlough of government workers deemed non-essential during the recent government shutdown.

As of the end of November, the number of pending cases in immigration courts surpassed 800,000, according to a report by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). Additionally, most immigration court hearings were canceled during the federal government shutdown, with the estimated number of cancellations surpassing 42,000 by Jan. 11 and each additional week of the shutdown likely to increase this number another 20,000 canceled hearings, according to the report. This delay could result in another three or four years of waiting for migrants who may have already been waiting two to four years for their day in court.

2018 broke the record for the number of decisions to grant or deny asylum claims by immigration judges, with a 40 percent increase from decisions during 2017 and nearly 90 percent increase from that of 2016, according to TRAC. Of the over 40,000 decisions, nearly two-thirds of those were denials, which had increased quicker than grants of asylum compared to previous years. In 2012 the denial rate hovered above 40 percent and has been rising ever since, with 2018 marking the sixth consecutive year of this trend.

With the current backlog in immigration courts, around 20 percent of asylum decisions took 12 months or less to decide, reads the report. For individuals unable to find an attorney to assist them, over half of those cases began within the same year. However, when the asylum seeker had representation, only about one in ten cases were decided in under a year.

Once granted asylum, an asylum seeker can apply for a lawful permanent resident status after one year, and four years after becoming a permanent resident the individual can apply for citizenship, according to the American Immigration Council. If the asylum seeker’s claim is denied, they have a right to appeal. Otherwise they are deported. On December 20th, Mexico reluctantly agreed to a deal proposed by the Trump Administration that would require all U.S. asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while they wait for their applications to be considered. Carlos Catarlo Gomez became the first to be deported out of the U.S. to Mexico on January 29 while he awaits his trial date later this year. The unfortunate reality for Gomez and thousands of other migrants seeking asylum is that many of these applications are rejected, and the wait in Mexico could prove to be dangerous.

Intolerance at Every Step of the Way

For those fleeing Honduras, violence and harassment didn’t end after leaving. “They’re facing violence at every step: Honduras, on the road, in Tijuana, and in detention,” says Vivian Farmery, a trauma social worker, parent of two LGBT kids, and member of direct action groups Rise and Resist and Gays Against Guns. This past November she traveled to Tijuana, Mexico with a handful of others for five weeks to see how they could assist the migrant caravan. During this time she recognized a need amongst the LGBT community seeking asylum and so decided to assist a shelter housing 55 of these migrants in Tijuana.

Before Farmery’s arrival in November, during the early hours of May 7, 2018, an unidentified individual shoved a mattress against the door of the Tijuana LGBTQ shelter and lit it on fire. The shelter, Caritas Tijuana, had been robbed by at least six armed individuals the day before this, according to Veronica Zambrano, a spokeswoman for Caritas Tijuana, as reported by America Magazine. There were people inside the shelter at the time of the fire, with the mattress placed to try blocking their exit. After safely escaping, the group went into hiding in a series of undisclosed shelters.

After an arduous search for the LGBT asylum seekers in Tijuana, Farmery located the group. “When I first met them they’d been in hiding. None of them had been in public,” says Farmery. “The first thing that we got to do is take nine people out for pizzas at a friend’s local pizza place. They came in looking terrified. The people are in shock, and the PTSD is bad, but by the end of the night we were all dancing and having fun. And the next day they invited me to the shelter.”

Farmery texted the shelter’s leaders that night asking what supplies she could bring. Their response: “FOOD!” When Farmery arrived with 10 to 12 bags of groceries, she found just one pot of beans in the kitchen to feed the 55 people in the shelter. That was when Farmery turned her focus from working in a variety of types of shelters in Tijuana to focussing her attention on the LGBT shelters, which seemed to have been forgotten. After executing fundraisers on Facebook, Farmery would wake up each morning to more donations to purchase food, sanitary supplies, and other supplies for the LGBT migrants.

During Farmery’s time in Tijuana there were 55 people in the LGBT shelter, with 20 of these individuals hoping to go to New York City. Now that Farmery is back in New York, she is applying to be a primary sponsor for three young gay men and one trans man she met in Tijuana. These four men, who don’t have family in NYC to sponsor them, are currently in detention centers. Farmery has also been meeting with organizations in the area to help coordinate efforts for other LGBT asylum seekers wishing to move to New York.

For a citizen to sponsor an asylum seeker, the sponsor must currently be either a U.S. citizen or Legal Permanent Resident. Additionally, the sponsor must have an address where they have resided for over one year, be able to provide a safe and comfortable location for the asylee to sleep, provide basic necessities, and have the financial means for support. The sponsor will receive the asylum seeker after they are released from detention and will remain as their sponsor for a period the two decide upon.

Upon returning to New York, Farmery hoped to find sponsors for all 20 LGBT individuals from the shelter in Tijuana looking to settle in New York City. However, she realized there were also people in Tijuana she had not met because they were in detention during her time in Mexico, and after being released from detention are being sent to New York. These individuals also need sponsors, so her mission has expanded. Since she has returned to New York, the four individuals that she is planning to sponsor have entered detention and are awaiting their credible fear interviews.

As many as 64 trans women are currently detained in facilities in Texas and New Mexico without primary sponsors, an attorney working with the women and coordinating efforts with Farmery told her. Over the coming months activists like Farmery along with organizations throughout the U.S. will be working to obtain sponsors for these individuals.

“We have a large problem with people being dumped from detention with nowhere to go, no resources, and occasionally no sponsors. Emergency shelters are chock full,” says Farmery. “So we need people to help coordinate all of the services they need, from being picked up after detention, to being brought to emergency shelters, to supplying food and clothing, to finding sponsors for them.”

Being held in detention has proven dangerous for some asylum seekers. In ICE custody, a transgender woman Roxana Hernández seeking asylum in the U.S. died on May 25, 2018. “That’s one reason we’re scared for them being in detention without sponsors because the feeling is that if they have sponsors, it shines a light on them through the process,” says Farmery.

Hernández joined more than 1,300 others to begin the long journey across Central America and Mexico on March 25th, 2018. Hernández applied for asylum at the San Ysidro Port of Entry into the U.S. on May 9 and was subsequently held in the “icebox,” a term given to the heavily air-conditioned detention centers in which migrants often spend multiple days. While in Customs and Border Protection custody, Hernández was held while “suffering cold, lack of adequate food or medical care, with the lights on 24 hours a day, under lock and key,” read a statement by the immigrant rights group Pueblo Sin Fronteras.

According to a report by ICE, “Hernández was admitted to Cibola General Hospital with symptoms of pneumonia, dehydration and complications associated with HIV.” Additionally, “LMC medical staff pronounced her deceased … and identified the preliminary cause of death as cardiac arrest.” The report went on to mention that Hernández was the sixth detainee to die in ICE custody in fiscal year 2018.

Guards had kept handcuffs on Hernández for so long that they heavily bruised her wrists, according to an autopsy paid for and reported by the Transgender Law Center. “She also had deep bruising and injuries consistent with physical abuse with a baton or asp while she was handcuffed” and shackled for days on end. Citing that her cause of death was dehydration and complications due to HIV, the report concludes “her death was entirely preventable.”

“Roxana traveled over 2,000 miles through Mexican territory on foot, by train, and by bus, because her last aspiration and hope was to save her own life,” read a statement from a group that organized the caravan. “She fled the violence, hate, stigma and vulnerability that she suffered as a trans woman in her country, Honduras, and also in Mexico.”

Roxana’s aspiration to save her own life echoes the thousands of others in the migrant caravans looking to escape persecution and violence in their own country. They are ultimately forced to embark upon an arduous journey, circumnavigating intolerance, prejudice, and a maze of government bureaucracy and oppression at every step of the way.

To follow updates on this topic and other news surrounding the migrant caravans, you can follow Diversidad Sin Fronteras and Pueblo Sin Fronteras on Facebook.

Garet Bleir is an investigative reporter working with Toward Freedom. To follow updates on this topic amongst other investigations, you can follow his work on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter. Kyle Andrew Smith is an investigative reporter working with Toward Freedom. You can follow his work on Facebook or Twitter.